Before painter Milton Avery’s works were featured in the world’s most prestigious museums—and long before they fetched bids in the millions—the artist now known for his playful use of color and diverse stylistic repertoire lived an under-the-radar life in Hartford, Connecticut. Laboring and clerking at various factories and offices, Avery, born in 1885, supported his family while painting and taking art classes in the hours before and after work. He was well over 40 when his art began receiving recognition; financier Roy Neuberger purchased 100 paintings, displaying them in galleries across the globe. Avery became well known and a mentor to artists like Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb.

The trajectory of Avery’s work, spanning about six decades, will be displayed in three galleries at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, in Hartford, from March 5 to June 5. The first large-scale survey of the artist in 30 years, Milton Avery brings together more than 60 works of art from throughout his career, from his most famous paintings to lesser-known landscapes, portraits, and abstractions (some on loan from his descendants) that helped establish Avery as a highly influential American colorist.

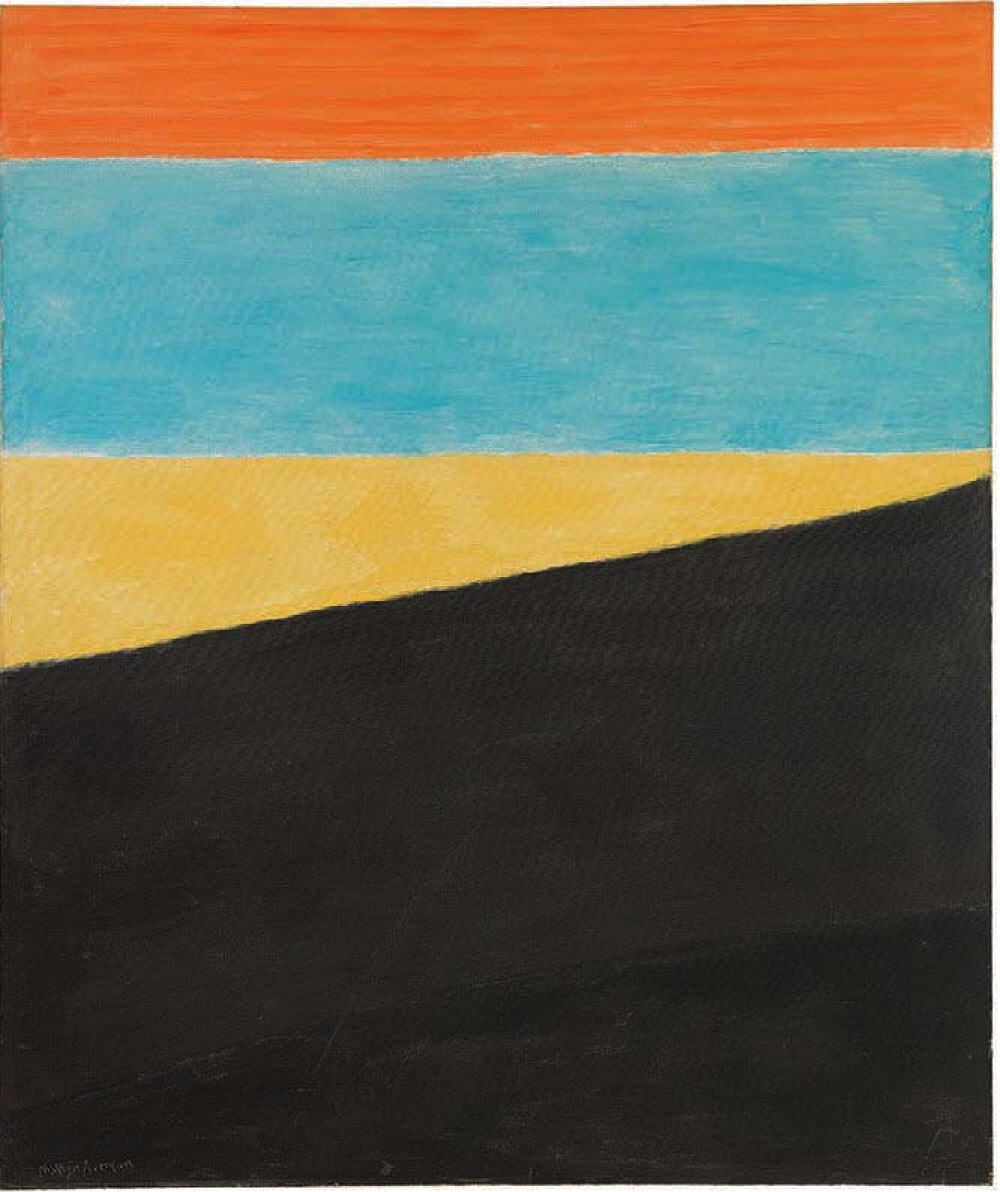

Boathouse by the Sea, 1959

2021 The Milton Avery Trust/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy Victoria Miro and Waqas Wajahat

Perhaps the greatest joy of the exhibit is witnessing Avery’s steady evolution as an artist. “You just see him, year after year, trying and experimenting with color and experimenting with shape,” says Erin Monroe, Krieble curator of American paintings and sculpture at the Wadsworth. “And it really does have this sort of breakout moment.” One such transitional painting is Blue Trees. Displayed among his early impressionistic works, it’s one of his first paintings to use dissociative color—portraying Vermont trees in playful blue hues. Avery’s early works mostly depict New England landscapes in an impressionistic style, but he adopted a more abstract expressionistic approach mid-career, leading to a sparser, minimalist style later in life. In addition to revealing one artist’s development, the exhibit also provides a wide look at American visual art from the turn of the century through the postwar era.

Though his blending of different styles makes Avery difficult to categorize, it makes for a dynamic—and fun—exhibit. “I think visitors will really kind of join him on a journey,” Monroe says, “and see that he never stopped experimenting and pushing the limits of what he could do with paint on canvas.”