Born into humble circumstances in East Boston in 1915, Richard Evans Schultes ’37, Ph.D. ’41, was a most unlikely candidate to become the archetypal Amazon explorer, the leading authority on mind-altering plants and fungi, and a “founding father” of rainforest conservation. The grandson of German and British immigrants, he spent his childhood as an outsider in a neighborhood dominated by Italians and the Irish, a formative experience that stood him in good stead when he later lived as an outsider surviving and thriving among indigenous Amazonian peoples.

Schultes entered Harvard College as a scholarship student in 1933, intending to study pre-medicine. Since plants and medicine were deeply intertwined at the time, he took a work-study job at the Botanical Museum and enrolled in a class on plants and human affairs taught by museum director Oakes Ames, A.B. 1898, A.M. ’99. In 1936, after Schultes devoured a book on the hallucinogenic effects of peyote and produced an excellent term paper on the subject, Ames funded him to do summer research with the Kiowa and other indigenous groups in Oklahoma. There, Schultes—who had not previously ventured outside New England—conducted one of the first field investigations of peyote employed as a healing sacrament by indigenous peoples. He reported that ingesting the cacti had induced experiences and visions “beyond the description of contemporary science.” His findings helped bring mescaline to the attention of the scientific community.

Back in the herbarium, he stumbled across a note attached to a specimen which claimed that Mexico’s Mazatec people ingested mushrooms for divinatory purposes. At the time, no scientist knew of any hallucinogenic fungi consumed by peoples of the Americas. In 1938, Schultes—then a Harvard graduate student—headed south to Oaxaca, where he collected “magic mushrooms,” leading to the scientific discovery of psilocybin.

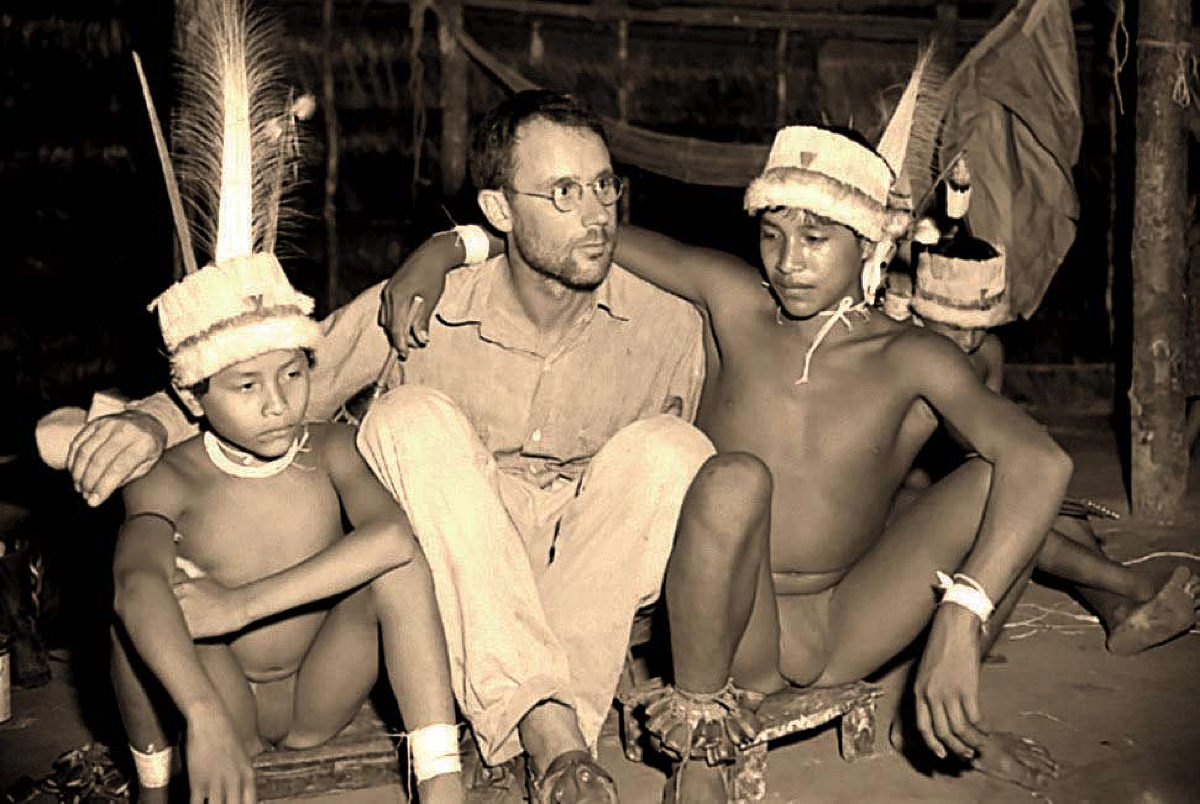

Schultes working with shaman Salvador Chindoy (who introducd him to ayahuasca)

Photograph courtesy of the Schultes Family and the Amazon Conservation team

Still greater exploits lay ahead. After receiving his Ph.D. in 1941, Schultes obtained a grant to study arrow poisons in southeastern Colombia, Amazonia’s most remote corner. Shortly after he arrived in Colombia, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and seized the rubber plantations in southeast Asia. As rubber was deemed an essential strategic warfighting material, the American embassy directed him to stay in the Amazon and search for new disease-resistant, high-yielding strains of rubber trees. Schultes remained in Amazonia for more than a decade, conducting the first detailed studies of the hallucinogenic ayahuasca vine as well as collecting thousands of other medicinal plants.

From left: in costume, Schultes and Yukuna colleague preparing for tribal dance; Schultes working with a Makuna boy

Photographs courtesy of the Schultes Family and the Amazon Conservation team

He returned to Cambridge in the early 1950s, eventually becoming the Botanical Museum’s director, and as a professor of biology taught the “Plants and Human Affairs” course in which he was once enrolled. Schultes created one of the most electrifying classrooms in Harvard history: the Nash Lecture Hall in the upper reaches of the museum, bedecked with demon masks, Amazonian dance costumes, opium pipes, blowguns, poison-tipped arrows, and herbarium specimens of hallucinogenic species.

Schultes’s books, lectures, and photographs elevated him to cult-hero status among those intrigued by alternate realities, and influenced writers like Alejo Carpentier, William Burroughs, Carlos Castaneda, and Aldous Huxley. Figures as diverse as biologist E. O. Wilson and Beat poet Allen Ginsberg hailed him as a personal hero and inspiration.

Schultes believed psychedelic substances could be powerful additions to the Western medicine chest, a prediction borne out by the development of cardiac beta blockers, derived in part from compounds extracted from the mushrooms he encountered in Mexico. Schultes also foresaw that hallucinogens could facilitate better understanding and more effective healing of the human psyche. His prediction has proven startingly prescient, with the advent of the current “Psychedelic Renaissance,” as mind-altering substances offer significant promise in the treatment of addiction, depression, PSTD, and other challenging afflictions.

Attending a ceremony

Photograph courtesy of the Schultes Family and the Amazon Conservation team

His scientific output was prodigious: he collected over 24,000 plant specimens (including at least 300 new to science—with more than 100 named in his honor) and published more than 450 articles. Adding to his legacy, he was among the first to proclaim that both the rainforest and the indigenous cultures that inhabited them were increasingly threatened, and that these societies and their botanical wisdom were disappearing faster than the forest itself.

In 1943, Schultes traveled to Chiribiquete, an exceedingly remote region of table-top mountains in the northwest Amazon that had been preliminarily mapped in 1917 by the eccentric Harvard geographer Alexander Hamilton Rice, A.B. 1898, M.D. 1904 (Vita, March-April 2013, page 36). He returned to the capital city of Bogotá and began advocating with Colombian colleagues for the government to declare Chiribiquete a protected area (an idea which finally came to fruition in 1989). Schultes retired from Harvard in 1985 but continued to speak and publish widely on the importance of rainforests and indigenous wisdom before his death in 2001.

Today, Chiribiquete is twice the size of Massachusetts, making it the world’s largest rainforest national park, home to stunning levels of biodiversity, and protecting three uncontacted indigenous groups and the world’s largest known repository of Pre-Columbian paintings. In terms of rainforest conservation, greater respect for indigenous wisdom, and better appreciation of nature’s therapeutic bounty, Schultes’s legacy endures.

[Editor's note: Edward Tabor wrote about Schultes and a hidden collection of paintings in the Botanical Museum here.]