I can't explain what I study at Harvard.

I am a women's-studies concentrator. After a two-year stint of floating through five large academic departments while regularly switching concentrations and trying to fulfill premedical requirements, I have--to put it mildly--seen all that Harvard has to offer. And I love women's studies.

For the first time in my life, I am actually engaged with my studies. I enjoy writing papers. The concentration is small and supportive, always happy to point me in the right direction or keep me up to date on fellowship and other academic opportunities, while providing me both individual attention (such as this semester's one-on-one tutorial) and the freedom to branch out along intellectual tangents as I see fit. These things cannot be said for my former departments, particularly larger ones where political biases and narrow academic constraints are a way of life.

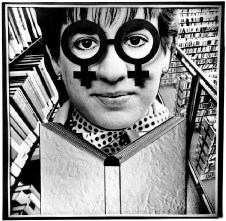

|

| Photomontage by Flint Born |

Equally important, within the concentration--much like at the Cheers bar--everyone knows my name. Though my mother uses such fluffy comments as fodder in ribbing my "warm and fuzzy" field, warm and fuzzy is good at a chilly place like Harvard, where attention from individual professors and genuine academic support--two key components of a quality education--are sometimes hard to come by. Women's studies offers easy access to Harvard's confusing web of resources. I have my whole life to fight bureaucracy; I don't need to practice as part of my undergraduate education.

Unfortunately, liking one's field and being able to explain what one studies are two different things. I generally try to hedge the topic, but inevitably a fellow student will ask what my concentration is. I usually respond straightforwardly: "I am a women's-studies concentrator." But Harvard students tend to be audacious, persistent, and intellectually questioning people:

"So, what exactly do you study in women's studies?"

"I study gender studies...it's much more than just women."

"Well, what besides women do you study?"

"Um, well, take gender, for example. The construction of gender is intimately attached to race, religion, class, and a myriad of other identity markers, and can't be isolated into one academic vault. It's broad."

That phrase usually suffices, and the conversation quickly turns into a question-and-answer session about my future plans with a women's-studies degree, or my "women's-studies opinion" of such popular commodities as the Easy Bake Oven. Or my fellow student will pause long enough for me to change the topic altogether, to the latest delicacies of the dining hall. Unless he or she persists:

"So you study everything?"

"It's kind of like cultural studies...we draw on many disciplinary traditions."

And then I run away.

So what exactly do I study? I am currently taking five courses in four departments. As in any small concentration, only a few courses are offered each semester, so students actively seek classes in other departments. Maximum freedom results and students develop their own courses of learning, essentially studying what they choose (within reason).

To prevent too much breadth, women's-studies concentrators are required to choose an "area of concentration," and take five upper-level courses that relate directly to that field. I have chosen to study gender and medicine, a pairing that aligns well with the certificate in health policy that I am pursuing, and satisfies my lingering pre-med interests.

As a student who previously found her interests flattened by the boring course mandates of larger departments, I thrive on the elasticity and freedom to design my own course of study: a responsibility that results in a greater investment in course work and higher levels of engagement. I now frequently read well ahead of my course syllabi--including the "suggested reading" (gasp!)--and often spend multiple days submersed in writing a paper because I'm interested in my studies. (My former routines involved polishing off papers in two to three hours and skimming hundreds of pages of weekly reading in the 15 minutes before section.) Amazing things can happen when a student's intellect is piqued and allowed to expand on its own.

Still, explaining that I do my studies falls far short of explaining what I study.

I was pondering this dilemma over coffee late one night, after a phone call in which an old friend had denounced my concentration as "pointless."

"Why," he asked, "did you ever leave government?"

In a fruitless attempt to change topics, I countered by arguing, "You just don't get it!"--a line of reasoning that, since its entrance into my pubescent vocabulary eight years ago, has inevitably gotten me nowhere. Luckily, friend and fellow women's-studies concentrator Laure "Voop" Vulpillières happened by just as I hung up. I figured that this lofty senior, a four-year women's-studies veteran, would definitely have the answers to my troubles.

"Voop, how do you explain women's studies when people ask?"

"That's so annoying! I can never explain it, especially to my mom."

"Okaaay, so if someone were to say, 'Voop, what do you study in school?' what would you say?"

"I don't know. I usually just try to change the subject as quickly as possible...whatever we study is really interesting though--why, what do you say?"

"Whatever I say, I end up sounding militant. So I try to say as little as possible."

"Yeah, me too. It's a bummer...hey, after I graduate, can you stay in school for a long time and keep studying women's studies, so you can tell me what to read?"

"Um, yeah, sure, for one more year anyway."

So there you have it: Neither of us has any idea of exactly how to explain what it is that we study, yet we both want to continue studying it forever. So, we continue to study away, saying very little, but enjoying ourselves immensely.

After Voop departed my room, I pondered for a while before telephoning a joint history of science/women's-studies concentrator to help me cope with my inability to explain my academic program. She recalled venting similar concerns in a meeting with a professor. The professor responded helpfully that "women's studies is not a field. It's an area of interest."

My friend went on to explain that women's studies applies to any field. In history of science, it explains how science has created and enforced its own definitions of sex and gender in society. In literature, it examines how various authors portray women and men in different historical moments and, by extension, the changing social construction of gender in society over time. In social studies, it analyzes the gender-based power dynamics of various political theories, and how these theories translate into the daily lives of both sexes. In essence, women's studies is looking at how gender operates in society across many different disciplines, while providing students with analytic tools that apply to any power dynamic. To me, this made sense.

I thanked my fellow student profusely for this explanation, and called Voop to tell her the good news. She was thrilled.

Not surprisingly, the wide application of women's studies is reflected in the structure of women's studies itself at Harvard. Women's studies is a committee, not a department, so each professor is affiliated with another field. Though I'm sure that some members of the women's-studies committee might disagree with the "women's studies as a field of interest" model--particularly those who want the committee to become a department--this explanation does justify the practical struggles of explaining the field, because it's interdisciplinary.

For my own purposes, I use women's studies in reference to my future profession (and current avocation), writing. I had initially assumed that women's studies would simply give me something intelligent to say about women, a useful skill in a market flooded with women's magazines. But through the process of intellectually tracing the position of women and gender in various social circumstances, I have learned how to trace the lines of power in any circumstance. It's like a lens with which to scrutinize any situation and instantly see what is happening on multiple planes. This ability is infinitely valuable to a fledgling writer, for whom the capacity to take common information and quickly see an interesting story spells the difference between career success and failure. Tracing power lines always makes a good story, because power dynamics decide who wins, why, and the details of ensuing fallout--all the interesting parts.

Not coincidentally, whenever Nieman Fellows or famous journalists speak with undergraduates on campus, they often recommend that young writers "find the margins" of any newsworthy situation, because that is where the good story lies. (Such margins are in direct opposition to the proverbial "center" of the story, which can be located by the mass of frantic, microphone-wielding reporters.) This strategy makes for a captivating twist on the status quo, and a fascinating--and, one hopes, self-supporting--way to portray the world. This is why I love women's studies: because it has become a pivotal piece of my path to writing renown by teaching me how to think in a manner equally applicable to academia and the real world.

In the end, has this new knowledge helped me come up with a succinct answer to that ever-bothersome question, "What exactly do you study?" Not in the slightest. But I know that I appreciate my concentration for the opportunity it allows me to use my own mind freely--and develop ideas accordingly--within academic boundaries. And at least I'm now very secure in my new answer: "It helps my writing and thinking, but I can't really explain it right now."