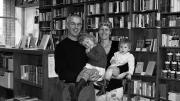

“People have blamed us for Borders closing,” jokes Brian Buckley ’90, owner of the Innisfree Poetry Bookstore and Café in Boulder, Colorado. Buckley and his wife, Katherine Hunter, opened their doors, and all 450 square feet of their store, last December. They sell beverages, pastries, and poetry—nothing else. No J.K. Rowling, no Stephanie Meyer, no Jonathan Franzen. There are only two other all-poetry bookstores in the country: Open Books, in Seattle, and the Grolier Poetry Book Shop, in Cambridge. You could say Buckley and Hunter are tapping a niche market. Or, given the failing health of bookstores, you could say they’re crazy.

“We wanted to make a place where people could sit and read a poetry book, and see someone else who has the interest they have,” Buckley explains. “The common space, the public space, it isn’t always there.” Read, see someone else, public space—the combination seems available enough: you can read among other readers in parks and subway cars, but those public spaces also mean cell phones, BlackBerrys, and iPods. What Buckley and Hunter seek to create with their bookstore is something different: “A kind of throwback. A gathering place for readers and writers.”

To this end, the bookstore hosts two to five events per week—ranging from readings by established poets to open-microphone nights. Such events in 450 square feet may sound like trying to squeeze a sonnet into a haiku, but Buckley and Hunter recently managed to double their space—the vintage clothing store next door closed—and they are fast becoming a community resource, joining Naropa University, home to the Jack Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, as part of Boulder’s burgeoning literary scene. “The café community drives the store financially, and the poetry is our reason for gathering,” Buckley says. Indeed, the café has done so well that Buckley and Hunter plan to add an outdoor patio to the store.

The couple met in 1990 in Lloyd Schwartz’s poetry workshop at UMass Boston, when Buckley was working as a teaching fellow for then professor of psychiatry and medical humanities Robert Coles ’50. All that courtship year, they made day-trips to Walden Pond, where they often read aloud to each other. For them, the link between Thoreau and poetry was fairly clear. When William Butler Yeats was a boy, his father read aloud to him from Walden; the echoes of that work in Yeats’s famous poem “The Lake Isle of Innisfree” are hard to miss:

I will arise and go now, and go to Innisfree,

And a small cabin build there, of clay and wattles made;

Nine bean rows will I have there, a hive for the honeybee,

And live alone in the bee-loud glade.

Hunter recalls, “We loved that Thoreau’s writing reached across an ocean and inspired a great poet.” Naming their bookstore Innisfree not only calls to mind a safe haven for solitary poets, but also gives a nod toward Yeats as a young reader who learned in his boyhood what a privilege being a reader is—the community it joins you to, even if you’re alone.

Buckley and Hunter say they’d like their bookstore to function something like a minor train station, with literary travelers returning and setting out again. Maybe trading tips—you ought to visit this Merwin; that Ashbery is great this time of year—or maybe just keeping their findings to themselves. In either case, their hope is that their Innisfree will serve as a physical acknowledgment of the experience of reading, that it will be an offering of fellowship not based on anything outward—as with Facebook or Twitter—but on the parts of ourselves more difficult to reveal. “It’s important for poets to feel that,” Buckley says. “To be together, even as we’re alone.”