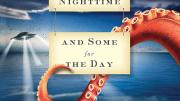

In his recent collection, Stories for Nighttime and Some for the Day (Penguin), the short stories of Ben Loory ’93 often begin with a direct, declarative sentence:

“A man is walking through the woods, when suddenly he sees Bigfoot.”

“A woman and her friend are in a knife store.”

“A boy meets a girl on a beach, and instantly falls in love.”

The stage is set, and the story ensues—usually short, with an unpredictable plot. Sometimes things take a turn for the worse, sometimes otherwise. Some stories evoke childhood terrors, others, the gritty preoccupations of adulthood. Humor, or the unexpected turn of phrase, appears slyly on the page. The language is beguilingly simple; the stories—“fables and tales”—are not. They often end with a metaphorical exclamation point—a surprising, yet appropriate, paradox. “The end of a story should feel like a birth,” Loory says, “painful and hopeful; frightening but inescapably right.”

Loory writes in a spare, pared-down style. “The choice I made from the beginning,” he says, “was to take out any extraneous details, anything that would take away from the emotional thrust of the story. I was trying to focus on character, and on a single emotional conflict.” The things “taken away” are the names of characters, adjectives, and quotation marks. “Loory’s sparse, unadorned prose,” wrote Michael Patrick Brady in The Boston Globe, “may seem at odds with the fantastical subject matter…but his restraint allows his big ideas to flourish without distraction.” His work has appeared in dozens of publications, ranging from The Antioch Review to ESPN The Magazine to The New Yorker.

After Harvard, where he concentrated in visual and environmental studies, Loory earned an M.F.A. from the American Film Institute, then worked as a Hollywood screenwriter for six years. “Screenwriting taught me to focus on story,” he says, “to externalize and dramatize and always keep things moving forward.” For several years, he also played mandolin, baritone sax, and accordion in an “American roots music” group, Soda and His Million Piece Band.

But sometimes Loory felt blocked as a screenwriter. He took a class in horror writing, began to write his short, enigmatic tales, and found the new form liberating; he has stuck with short fiction ever since. “It was nice to work on something that was more surprising,” he says, and this element—a plot’s sudden, unexpected change of direction on a turn of phrase or action—is at the heart of his fiction. “I just try to write stories the way I like to hear them,” he explains: “short, evocative, mysterious, sometimes scary, and compelling.”

“The Hunter’s Head” begins, “A hunter returns to his village one night with a severed human head in one hand.” A village boy spies on the hunter as he makes daily treks into the jungle, returning each time with a decapitated human head. The heads, mounted on stakes, speak to the boy and urge him to act. He does, and the hunter’s own head soon joins the others, atop a stake. The story ends, “The boy slips into the jungle and is gone,” leaving readers to wonder if the boy is fleeing to avoid punishment, or has acquired a taste for headhunting himself.

In other tales, a duck falls in love with a rock; an octopus lives in a house and drinks tea; a moose befriends and then parachutes with a man. “Fables is a word I started to use to give editors a heads-up that these stories are stylistically different,” Loory says. Unlike Aesop’s, his don’t have morals. “They aren’t really fables, but there is something fable-like about them,” he says. “To me, the point of a story is the feeling it produces. I’m more interested in writing music than propaganda.”

Some stories seem to have a spiritual dimension. In “The Tunnel,” “Two boys are walking home from school when one of them sees a drainpipe set back in the woods.” As we fear, one of the boys crawls into the pipe, where “the tunnel closes in—bit by bit, slowly…filthy walls press his arms against his sides.” He continues, and gets stuck, and “It is then—and only then—that the boy sees the door. The little door in the wall right behind him.”

Yet most of the tales tend toward the light, and have more cheerful resolutions. In “The Book,” a woman buys some books, and one is full of blank pages. This enrages her and leads to various misfortunes until, decades later, as an old widow, she finds the book on the shelf and finds therein a photograph of herself and husband, “on the very first day that they met.”

They’re standing together on that beach; in the distance is a sunset.

Oh, says the woman, look at that.

And a smile spreads across her face.

And then the book seems to open itself, and there’s her life on the page.

This same element of surprise will likely startle in Loory’s future work: he is now at work on an illustrated children’s book, and another collection of linked short stories that all take place in the same town. He gives many readings, and enjoys doing them: “My stories are designed to be read out loud,” he says. “It’s a big part of my writing process. It always helps me to hear what’s working, and what isn’t.”

A confessed night owl, Loory says that these 40 tales were written in both the nighttime and the day. “I have one rule in writing, which is that I write whatever comes out,” he says. “And when I sit down to write, short stories are what come out.”