Harvard got into the book-publishing business in the 1640s. It happened this way. In 1638, Puritan clergyman Josse Glover sailed for Massachusetts with his wife, Elizabeth, and their children, and a locksmith named Stephen Day and his family. The Glovers brought with them a printing press, type, and paper to print on. Josse died on the voyage, Elizabeth moved into a big house in Cambridge, and set up the Days in a smaller house with the printing equipment.

In 1640 came another clergyman, Henry Dunster, 30, who was quickly appointed the first president of Harvard College. He married the widow Glover and moved into her house. She died in 1643, Dunster took possession of the press, type, and paper, remarried, and moved with the printing gear and the five Glover children into a house built for him by the College in Harvard Yard. Very likely the press was operated by Stephen Day’s son, Matthew, who was also the College steward.

The third item to issue from this press was the first real book produced in the English colonies, The Whole Book of Psalmes Faithfully Translated into English Metre (1640), later called the “Bay Psalm Book.” Colonists sang praises to God with this volume in hand. A good book, like most that have followed it from Harvard. (It also turned out to be a good investment. Only 11 copies of the psalter are known to exist today, and in December 2012, the congregants of Old South Church in Boston voted overwhelmingly to sell one of their two copies at auction to fund repairs, air conditioning, and so forth. Sotheby’s estimates it will fetch between $10 million and $20 million.)

The press moved into another building in the Yard and clattered busily, turning out books and pamphlets and other matter for the College and for outside customers until Harvard abandoned the effort in 1692. In 1802, the President and Fellows voted to establish a printing office to print for and at the direction of the University, but sold the operation in 1827. Harvard’s third printing venture came in 1872 with the establishment of a printing office and, in 1892, a publication office, both in University Hall in the Yard. They later moved to more spacious quarters in Randall Hall, on the site where William James Hall stands today like an immense big toe. See the presses there, above, and the composing room, opposite. Publication staff sat on a balcony behind a glass partition overlooking the compositors. (Printing and publishing would split apart organizationally in 1942.) In 1913, the publication office became Harvard University Press. It celebrates its centennial this year with various undertakings:

Book courtesy of the Harvard University Press and Houghton Library; photograph of book by Jim Harrison

A book on Chaucer by George Lyman Kittridge, published in 1915 and still in print in 1970

• The backlist lives forever. The Press has published more than 10,000 titles since its founding. Unlike commercial publishers, who pulp slow-selling books mere months after their launch and move on to new speculations, university presses tend to keep books in print for very long periods—estimable behavior, academic authors would say. But sometimes, of course, bad things happen to good books and they go out of print. Through a partnership with the German publisher De Gruyter, HUP will bring back into print, in either e-book format or print-on-demand hardcover, all currently unavailable titles for which the press still has publishing rights, starting this spring.

• Interactive Emily, etc. This year will bring an open-access digital Emily Dickinson Archive. It will showcase her manuscripts and encourage the reader to study the poet’s own handwriting, word choice, and arrangement; read and compare transcriptions of her poetry through time; and conduct new scholarship with annotation tools.

The digital Dictionary of American Regional English will enable readers to find regional words they already know but also search by definition, browse by region, and flip serendipitously through the dictionary to synonyms and new, unusual words—“cattywampus,” perhaps. It will also contain a wealth of information, along with audio of field recordings from when the original hardcover edition of the multivolume dictionary was compiled in the late 1960s.

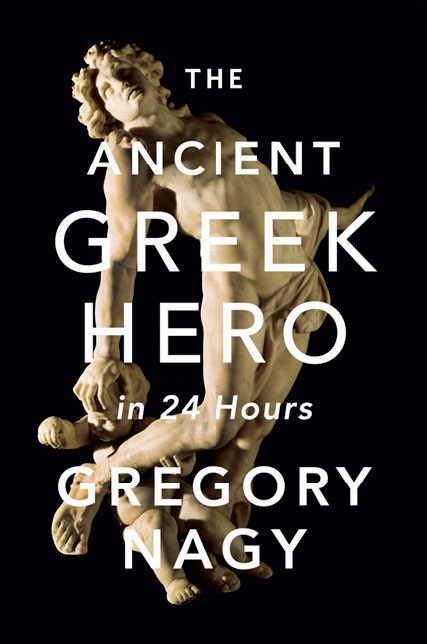

The Press will formally announce this year details of a program to come in 2014: the complete Loeb Classical Library, more than 500 volumes, will be available in digital format, searchable, so that one will be able to get in bytes and bits all that is important in classical Western literature, with Greek or Latin text next to English translations.

• Exhibitionism. Books to conjure with, interesting records, correspondence with notable authors, photographs, and ephemera worth looking at, are on display at the Houghton Library in Harvard University Press: 100 Years of Excellence in Publishing, through April 20. Examples are shown here.

• New look. To commemorate its anniversary and welcome the future, the Press has enlisted the design firm Chermayeff and Geismar to create a logo and visual identity and is sending into the world books and publicity it hopes are stylishly dressed (see “Printer’s Mark”). With a backward glance, one notes that during the 1920s some of the greatest of book designers—Bruce Rogers, D.B. Updike, David Pottinger, and W.A. Dwiggins, variously associated with the Printing Office—laid hands on the Press’s output.

• Celebrations. There’s a birthday website with candles one may visit, www.hupcentennial.com, and when the American Association of University Presses meets in Boston in June, there will be learned parties.

Why establish a press? Back in 1912, when the founding fathers were trying to drum up enthusiasm and money for a full-fledged university press, they put together a circular giving seven reasons for wanting such a thing. “One was that an adequately endowed publication center would add greatly to Harvard’s reputation for scholarship,” the late Max Hall, NF ’50, HUP’s one-time editor for the social sciences, related in his 1986 book Harvard University Press: A History. “Another was that it would contribute materially to the advancement of knowledge....The authors strongly made the point that a learned press ‘would not be in any sense a competitor to the commercial publishers since its chief function would be the issuing of books that would not be commercially profitable.’”

Thomas J. Wilson, the fifth director of the Press, served from 1947 to 1967 and raised the prestige of the organization at Harvard and in the publishing world. He uttered a mission statement famous in his profession: “A university press exists to publish as many good scholarly books as possible short of bankruptcy.”

Book courtesy of the Harvard University Press and Houghton Library; photograph of book by Jim Harrison

A History of American Magazines.

Book courtesy of the Harvard University Press and Houghton Library; photograph of book by Jim Harrison

Eleanor of Aquitaine (1950), the Press’s first Times bestseller

The first of many Pulitzer Prizes for a Press book came in 1939, for Frank Luther Mott’s History of American Magazines. The first of many Bancroft Prizes for books about diplomacy or the history of the Americas came in 1951 for Arthur N. Holcombe’s Our More Perfect Union: From Eighteenth-Century Principles to Twentieth-Century Practice. Now and then, an actual bestseller slips onto the list, bringing a change of pace and elation to the Press staff. The first of these was Amy Kelly’s Eleanor of Aquitaine and the Four Kings, 1950.

In its centenary year, as in recent years, the Press will publish about 180 books, not counting paperback reprints. It’s no pee-wee enterprise. Some highlights of 2013: Walter Johnson’s River of Dark Dreams: Slavery and Empire in the Cotton Kingdom, just out; Gish Jen’s Tiger Writing: Art, Culture, and the Interdependent Self, drawn from her Massey Lectures in the history of American civilization, due in March; the first English translation of Albert Camus’s Algerian Chronicles, coming in May; and in the fall Martha Nussbaum’s Political Emotions: Why Love Matters for Justice.

Naturally, the Press has had its good days and bad. In his history of the place, Max Hall summed up: “During the centuries since the first printing press arrived in North America, the publishing of books by Harvard has taken several forms, and the maturing of the central publishing department, even after 1913, has been a slow and erratic process. President Eliot founded the Printing Office and Publication Office, and would have founded a more fully organized university press if the financial means had been available. President Lowell wanted a university press, but only with misgivings did he agree to start one, because he feared that it would not be self-supporting—and it wasn’t. President Conant tried to abolish the Press because he did not think the University should be ‘in business.’ But he failed, and the University in the second half of his administration strengthened the Press instead, recognizing for the first time the need for making ample funds available for working capital. President Pusey had no financial worries about the Press until the very end of his tenure. [Under the four-year directorship of Mark Carroll, the Press published such seminal works as John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice, E.O. Wilson’s The Insect Societies, and Notable American Women: 1607-1950, edited by Edward T. James and Janet W. James. It also ran large, unanticipated, and unsatisfactorily explained deficits, and Carroll left his job, not quietly, in 1972.] President Bok inherited a crisis during which Harvard gained some additional experience with academic publishing. He told the new director in 1972 that he wanted the best scholarly press and also a very professional press and saw no reason why the two purposes should interfere with each other.”

A book offered for a fee in print and free online in edX, the nonprofit Harvard-MIT partnership for interactive study on the Web

“It would be hubristic of me, I think, to assess our place in the world,” says today’s Press director, William P. Sisler, in response to a question to that point, “but the number of positive reviews we receive for our books and the awards won suggest we’re doing okay. To the best of my knowledge, we have not been a drain on the University in the last 40-some-odd years (I’ve been here going on 23, and can attest to that), so we continue to be self-sufficient from two sources, our sales and our endowment. Obviously, both we and the University will be happier if that situation continues, though it doesn’t get any easier!”

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,