Human existence changed irreversibly after the innovation of indoor plumbing and municipally supplied water and sewage treatment. The advent of electricity—and of pasteurization, automobiles, the telephone, penicillin, the polio vaccine, and many more inventions—also changed life as we know it. Analyzing such familiar, seemingly commonplace innovations, Robert J. Gordon ’62 addresses a question of pressing importance in the United States today, and indeed around much of the world: how does economic growth occur? He distills many of these innovations, and presents a lucid history of their economic impact on living standards in the United States during the last century and a half.

Although the topic might at first seem dull, this panoramic book makes good reading because Gordon, Harris professor of the social sciences at Northwestern University and one of the foremost analysts of economic growth, displays exemplary self-awareness about what standard economic measurement can and cannot do well. He uses the standard government statistics, but does not stop there, drawing widely from other sources and anecdotes (hence the information on plumbing, cars, and so on) to tell a rich story about changes in living standards.

The marriage of “innovation,” “history,” and “economics” might sound like an enormous agenda—too much for one book. But Gordon organizes copious details about history into very readable chunks, and his narrative moves forward at an engaging pace. Nonetheless, a tension arises when he turns to the present, in the last fifth of the volume. That section is almost a different book in tone and substance, containing unresolved policy debates and questions, and consequential conclusions that have generated professional disagreements with wider import for innovation policy: is the era of innovation-fueled growth over, and does the United States face a more challenged economic future?

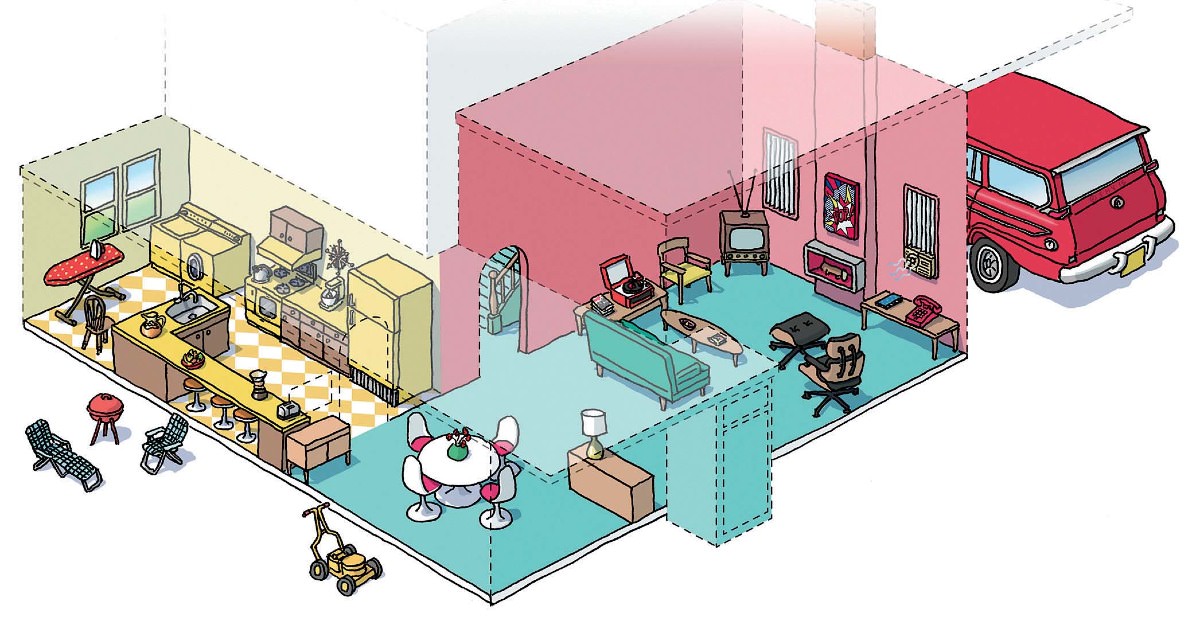

Illustration by Susan Hunt Yule

Innovation and GDP. One proposition motivates Gordon’s inquiry: Innovations come along only once in the history of a country’s growth, so each unique innovation changes Gross Domestic Product (GDP, a measure of the total flow of economic activity in the domestic economy in a given year) only once. Gordon, a master of GDP measurement, sets himself a tall task: to trace the links between different innovations and measured growth in GDP.

He doggedly pursues this somewhat technical project through a “greatest hits” list of post-Civil War and twentieth-century innovations: electricity, telephony, rail shipping, sanitation, the automobile, mass-market medicine, housing, and television. The book wanders delightfully into unobvious territory, too, devoting many pages to the rise of frozen food, the use of time-saving devices in households, the importance of air conditioning for the South and West, and the spread of retail catalogs into rural America.

But not even a book as sweeping as this one can do everything, and that poses a problem, because in practice there cannot be a clear boundary between Gordon’s “greatest hits” and those innovations not on his radar. Some of the missing discussions are puzzling. Consider his treatment of communications technology: Gordon has a great discussion on the invention of the telephone and its spread, and later acknowledges the contribution of cell phones and smart phones. I would have liked more on the value of mobility. Does Gordon think the new mobility of communications is of minor importance for living standards? Mobile devices have certainly rendered the telephone booth obsolete—and a large fraction of the residential landline business has gone away. Nor does he delve deeply into innovation at the Bell System, beyond token stories about the invention of the transistor. Despite its lumbering size and regulatory obligations, the Bell System could be innovative. For example, it deployed electro-mechanical and then digital switches—major technical achievements that linked the country. Did Gordon not devote time to the topic because he did not think it mattered, or because he did not look into it?

The present—and prospects. As noted, Gordon turns his attention in the final 20 percent of his book to contemporary events: an important and seemingly volatile period. Following strong growth for almost three decades after World War II (when per capita growth averaged more than 2.5 percent per annum), the United States experienced slow growth in the 1970s and ’80s (far less than 2 percent between 1973 and 1995), until the Internet boom between 1995 and 2001 (when the per capita growth rate accelerated to over 2.5 percent again). Economic growth has since slowed once more (to notably less than 2 percent), reflecting the dot-com bust, the financial meltdown during the last decade, and the sluggish recovery since. That might seem like a small change, but growth rates compound and accumulate, and can make enormous differences if they persist.

Gordon foresees more slow growth ahead, a forecast that has generated attention and criticism from within the economic profession. The writer who so celebrated historical innovations transforms into someone else. Although he makes upbeat observations about airline deregulation, the personal computer, the CT (computed tomography) scanner, and e-commerce, his mood becomes mostly dismal. He does not foresee many major innovations on the horizon (he illustrates the argument with discussions about medicine and information technology)—and so he concludes the growth engine has declined.

This discussion is incomplete and unbalanced. Gordon poses a question that requires a thorough and definitive analysis of why the market for information technology contains or lacks the capacity to renew itself. A thorough analysis must grapple with the many pathways through which radical innovation emerges today. Yet Gordon pronounces his skepticism with breezy confidence.

In examining the Internet, for instance, he takes note of the value of mobile telephony and the PC, but remains skeptical of exaggerated claims for information technology (as are most of us). But perhaps he protests too much: Gordon seeks important innovations that simultaneously change consumption, alter the allocation of leisure time, and upend standard business processes across the entire economy—and finds the IT revolution lacking. Again, perhaps, the scope of his inquiry is too limited. One would have expected him to embrace the rise of the commercial Internet, which has wrought all of those changes for a sustained period, and continues to do so. Gordon lauds some of these effects, such as the ascent of Amazon, but then displays no serious appreciation for how much business processes have changed as a result, nor how those changes supported the expansion of world trade—and specifically, U.S. exports and imports. Indeed, he remains a skeptic, providing reasons why no major, innovative information technology is likely to arise tomorrow or contribute to vigorous economic growth.

His discussion about medical technology reflects the same tension. Many issues merit attention, and Gordon highlights those, but his discussion is incomplete without a survey of advances in many areas of medicine. Assessing the capacity of the system to yield radical improvements in living standards requires a nuanced, thorough analysis. Again, Gordon has posed a question and reached a conclusion that seems unresolvable given the scope of his treatment.

By his final chapter, the ebullient economic historian has disappeared, replaced by a downbeat macroeconomic forecaster who enumerates a number of challenging social and economic factors, such as inequality in consumption and underfunded entitlements (collectively, Gordon calls them “headwinds”), that make growth difficult. He argues that these headwinds will overwhelm the impact of any but major innovations, and forecasts that few of those will appear on the horizon. If that is the case, the social implications are enormous. But if this forecast is unsupported and fundamentally unresolvable on the basis of the evidence presented, then his conclusion seems unwarranted and hasty.

***

I respect Robert Gordon for what he has achieved. He has assembled an enormous amount of historical evidence, and framed a provocative argument about contemporary experience.

It certainly made me ponder some big questions. If prior generations picked the low-hanging fruit, do modern innovators face a thornier and costlier set of challenges? What changes would raise the likelihood of major innovations from the U.S. university system, corporate labs, the Department of Defense, and Silicon Valley?

If prior generations overcame their headwinds, why can’t ours? Today’s headwinds do not look any worse than yesterday’s: primitive scientific instrumentation, bank panics, world wars, and the Great Depression, not to mention the fires that razed Chicago and San Francisco, to name just a few. And what are we to make of the unique status of the United States on the global stage today? It is still the world mecca for innovators, and governments around the globe still admire the U.S. innovative engine. I wish Gordon would lighten up, and cut the present generation of innovators some slack.