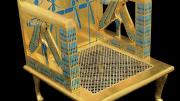

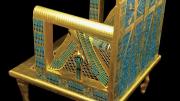

Much is still unknown about the world of the ancient Egyptian elites, whose lives are fossilized in the riches of the ruins at Giza —and reflected by the luminous throne that sits on the second floor of the Harvard Semitic Museum. Crafted from cedar wood, covered in delicate gold foil, and inlaid with turquoise-colored faience tile, the piece replicates a 4,500-year-old chair that belonged to Queen Hetepheres, the mother of King Khufu, who built the Great Pyramid at Giza. How the throne was used, or whether it was used at all, remains elusive. “Sometimes things are used in daily life and put into the tomb, and sometimes they’re dummy objects created for burial,” says King professor of Egyptology Peter Der Manuelian. “Whether it’s built for use in daily life or in the afterlife is always the question.”

The throne was discovered by accident, shattered into thousands of pieces, by a joint Harvard-Museum of Fine Arts expedition in 1925, when a photographer stumbled (literally) into a burial shaft containing the queen’s tomb. Three years after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb, the public remained hungry for stories about the treasures of ancient Egypt. “This was a sensational discovery,” says Manuelian. “For the next two years the team spent all their time down there, lying on mattresses with tweezers, picking up every tiny fragment.”

Most of the furniture in the queen’s tomb—a bed, a more modest wood throne, a handsome sedan chair—had been reconstructed for display in Cairo and at the MFA, but no one had tried to reproduce the grander of the two thrones. Flanked with falcons on either arm and inlaid with tiny pieces of tile depicting beetles, arrows, and other Egyptian iconography, it appeared too complex to imitate, even working from the excavation team’s detailed sketches.

It took a crew of craftsmen at the Harvard Giza Project three years and 1,000 hours of labor, plus 3-D imaging technology and a computer-driven carving machine, to rebuild the throne. Just figuring out how to reproduce the faience tiles took a year. “The Egyptians’ artists were far better,” jokes Rus Gant, lead technical artist of the Giza Project.

To be fair to the Semitic Museum, the royals had vast resources at their disposal. “This was a very tightly centralized period in Egyptian history,” Manuelian says, “where the ruling family and their relatives were totally in charge.” He calls the project “experimental archaeology,” a process meant to shed light on the Egyptians’ artistic methods, and tell us something of their hidden lives.