The Commencement-week speakers wove together affectionate observations, searing personal anecdotes, an explicit evocation of the apocalypse (in President Drew Faust’s address, making the case for universities’ role in troubled times), and that old standby, avuncular advice (from Steven Spielberg).

Kindness: A “Subversive Thing”

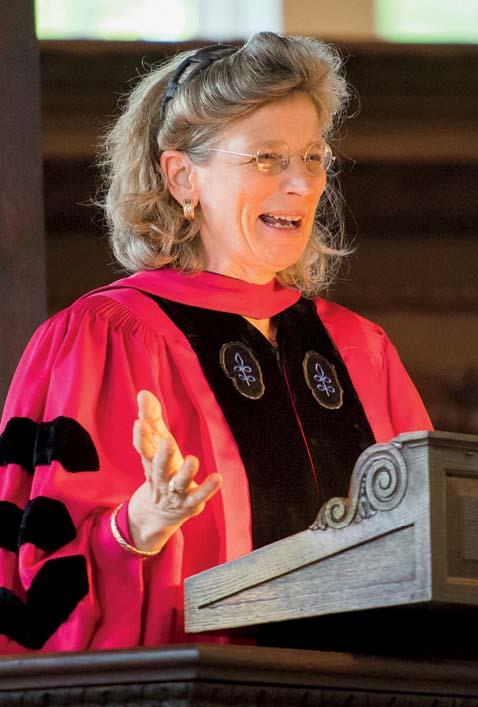

At Harvard Divinity School’s Multireligious Commencement Service, in Memorial Church, faculty speaker Kimberley C. Patton, professor of the comparative and historical study of religion, evoked the school’s spirit:

“What is it like to teach there?” I’m sometimes asked. I usually answer, wearily or humorously, depending on the day: “God bless them, they’re all trying to save the world.” How weird and wonderful to see you world-savers today, and tomorrow, not as independent self-actualizing graduate students, but instead as tenderly encumbered, trailed by your nearest and dearest. Your makers. Today your tribesmen are not only in your thoughts as you toil far away in Cambridge, but now in plain sight, like dreams suddenly manifest in the waking world, loving you, annoying you, photographing the life out of you. And sometimes, asking—behind your backs, or maybe right in front of you—what on Earth will she do with a Divinity degree? Especially in this economy.

Kimberley C. Patton

Photograph courtesy of the Harvard Divinity School

What they would do, she hoped, was apply what they had learned:

You’ve spent years of training to become scholars and ministers, to become activists, to become writers, to become literate in what has always been one of the oldest and most persistent realms of human experience, the one that calls the shots for all the rest of them. There is no chronic injustice or pernicious evil in this world that can be solved without understanding the profound role that religion, culture, and ideology, intertwining as they do, play in its action.

And in doing so, pursue the hard work of being kind and promulgating kindness, beyond the seemingly limiting reach of kinship and like-mindedness:

Kindness is so often dismissed as the anemic, saccharine twin of its more robust siblings in the terminology of world religions: compassion in Buddhism, mercy in Judaism and Islam, love in Christianity. Worse, kindness is often seen as a cowardly way to duck agonizing ethical dilemmas that involve the surrender of power, privilege, or capital; or to ignore systematic violence against female, brown, child, or gay and transgender bodies; or to hack the gnarly challenge of injustice while racking up gold stars for being nice. But kindness is not niceness. It is, instead, a powerful and subversive thing. It is something that anyone can practice, even if she cannot bring herself to feel compassion, or mercy, or love.

No matter the challenge, she urged, “Let us nevertheless practice kindness, the gateway to compassion, the gateway to justice.”

“My Hand on Fire”

During the Commencement Morning Exercises, He Jiang related a story stemming from his youth in a farming community in Hunan province, far from images of today’s modern, urban China—an incident that shaped his drive to pursue research on flu, malaria, and hepatitis, and to disseminate knowledge to less privileged areas, like his home village.

He Jiang

Photograph by Stu Rosner

When I was in middle school, a poisonous spider bit my right hand. I ran to my mom for help—but instead of taking me to a doctor, my mom set my hand on fire.

After wrapping my hand with cotton, then soaking it in wine, and putting a chopstick into my mouth, she ignited the cotton. The flame quickly engulfed my hand. The searing pain made me want to scream, but the chopstick prevented it. All I could do was watch my hand burn—one minute, two minutes—until mom put out the fire.

You see, the part of China I grew up in was a poor, pre-industrial farming society. When I was born, my village had no cars, no telephones, no electricity, not even running water. And we certainly didn’t have modern medical resources. There was no doctor to see about my spider bite.

For those who study biology, you may have grasped the science behind my mom’s cure: heat deactivates protein, and the spider’s venom is simply a form of protein. It’s cool how that folk remedy incorporates basic biochemistry, isn’t it? But I am a Ph.D. student in biochemistry at Harvard, I know that better, less painful treatment existed. So I can’t help but ask myself, why I didn’t receive one at the time?

“Truth Cannot Simply Be Claimed”

In troubled times, President Drew Faust told the afternoon audience, universities need to restate their basic values:

We sing in our alma mater about “Calm rising through change and through storm.” What does that mean for today’s crises? Where do universities fit in this threatening mix? What can we do? What should we do? What must we do?

We are gathered today in Tercentenary Theatre, with Widener Library and Memorial Church standing before and behind us, enduring symbols of Harvard’s larger identity and purposes, testaments to what universities do and believe at a time when we have never needed them more.…

Drew Faust

Photograph by Stu Rosner

We look at Widener Library and see…a repository of learning…a monument to reason and knowledge, to the collection and preservation of the widest possible range of beliefs, and experiences, and facts that fuel free inquiry and our constantly evolving understanding. A vehicle for Veritas—for exploring the path to truth wherever it may lead. A tribute to the belief that knowledge matters, that facts matter—in the present moment, as a basis for the informed decisions of individuals, societies, and nations; and for the future, as the basis for new insight. As James Madison wrote in 1822, “a people who mean to be their own Governors, must arm themselves with the power which knowledge gives.” Or as early twentieth-century civil rights activist Nannie Helen Burroughs put it, “education is democracy’s life insurance.”

Evidence, reason, facts, logic, an understanding of history and of science.…These are the bedrock of education, and of an informed citizenry with the capacity to lead, to explore, to invent. Yet this commitment to reason and truth…seems increasingly a minority viewpoint. In a recent column, George Will deplored the nation’s evident abandonment of what he called “the reality principle—the need to assess and adapt to facts.” Universities are defined by this principle. We produce a ready stream of evidence and insights, many with potential to create a better world.…

So what are our obligations when we see our fundamental purpose under siege, our reason for being discounted and undermined? First we must maintain an unwavering dedication to rigorous assessment and debate within our own walls. We must be unassailable in our insistence that ideas most fully thrive and grow when they are open to challenge. Truth cannot simply be claimed; it must be established—even when that process is uncomfortable. Universities do not just store facts; they teach us how to evaluate, test, challenge, and refine them. Only if we ourselves model a commitment to fact over what Stephen Colbert so memorably labeled as “truthiness”…can we credibly call for adherence to such standards in public life and a wider world.

We must model this commitment for our students, as we educate them to embrace these principles—in their work here and in the lives they will lead as citizens and leaders of national and international life.

“My Intuition Kicked In”

Steven Spielberg, visibly thrilled to be a Harvard honorand, mixed personal anecdote, filmic wisdom, and conventional graduation tropes:

I left college because I knew exactly what I wanted to do, and some of you know, too, but some of you don’t.…Maybe you’re sitting here trying to figure out how to tell your parents that you want to be a doctor and not a comedy writer. Well, what you choose to do next is what we call, in the movies, “a character-defining moment.” Now, these are moments that you’re very familiar with, like…Indiana Jones choosing mission over fear by jumping into a pile of snakes. Now, in a two-hour movie, you get a handful of character-defining moments. But in real life, you face them every day. Life is one long string of character-defining moments, and I was lucky that at 18, I knew exactly what I wanted to do. But I didn’t know who I was.

How could I, and how could any of us? Because for the first 25 years of our lives, we are trained to listen to voices that are not our own. Parents and professors fill our heads with wisdom and information, and then employers and mentors…explain how this world really works.…[B]ut sometimes doubt starts to creep into our heads, into our hearts, and even when you think, “That’s not quite how I see the world,” it’s kinda easier just to nod in agreement and go along, and for a while I let that going-along define my character.…

But then I started paying more attention. And my intuition kicked in. I want to be clear that your intuition is different from your conscience. They work in tandem, but here’s the distinction. Your conscience shouts, “Here’s what you should do,” while your intuition whispers, “Here’s what you could do.” Listen to that voice that tells you what you could do. Nothing will define your character more than that.