The debut of “Beyond Words”—on September 12 at Houghton Library and Boston College’s McMullen Museum of Art, and 10 days later at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum—represents the culmination of scholarly toil by Jeffrey F. Hamburger, Kuno Francke professor of German art and culture, and William P. Stoneman, curator of early books and manuscripts, initiated at the beginning of this millennium. A fitting gestation, perhaps, for an exhibition of some of the most important works created in human history, themselves extending back well into the prior millennium. Yet the 261 items scheduled to be displayed at the exhibition’s three venues, from 19 Boston-area libraries and museums, are only a fraction of the nearly 3,000 medieval and Renaissance manuscripts that the two scholars and their colleagues have examined since they began their project in 2000.

Stoneman recalls Hamburger’s interest in exploring local resources for his research and teaching (of late including a General Education course, “Openings: The Illuminated Manuscript,” and a freshman seminar, “The Book of Hours: Picturing Prayer in the Middle Ages”). Both knew about some of the treasures at the Boston Public Library, the Museum of Fine Arts, and Wellesley College, along with Houghton’s riches. But, Hamburger says, they suspected that some of Harvard’s holdings were less well known to scholars than they should be—and indeed, the exhibition has examples from the University’s business, divinity, law, and medical libraries as well. Even among accessible items, their research proved fruitful: fellow curator Anne-Marie Eze, formerly of the Gardner Museum, identified a prayer book in Houghton as the personal prayer book of Pope Julius III; the volume contains a previously unknown portrait of the mid-sixteenth-century pope—a vivid illustration of the treasures awaiting scholars’ attention. Such discoveries are, in Stoneman’s words, “hidden in plain sight.” The Greater Boston holdings, Hamburger says, are the largest group of medieval and Renaissance works in North America to have remained so little known to researchers and the public.

No longer. Recent exhibitions in Philadelphia and Cambridge, England, did much to broaden appreciation of such collections. “Beyond Words” ought to have the same effect here. The consortium of lending institutions is important in itself. So is the cooperative work by those institutions’ curatorial and conservation staffs, and the deep engagement of Hamburger, Stoneman, Eze, and their exhibition colleagues Nancy Netzer, professor of art history and director of the McMullen Museum at BC, and Lisa Fagin Davis, executive director of the Medieval Academy of America (who teaches at Simmons College’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science, and is proprietor of the “Manuscript Road Trip” blog).

The exhibition’s reach extends online (beyondwords2016.org); into print (an enormous eponymous catalog with 83 contributors, designed, edited, and published by the McMullen Museum, and distributed by the University of Chicago Press); to an international conference at the three venues, November 3-5; into Hamburger’s and Davis’s classes this fall; and worldwide, through Hamburger’s medieval modules in the HarvardX course “The Book.”

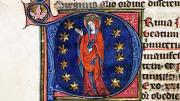

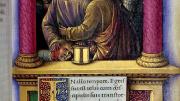

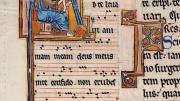

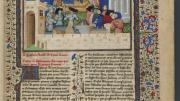

Because the languages and scripts in which the manuscripts were created are not accessible to lay readers, the items chosen for display emphasize, as the subtitle puts it, “Illuminated manuscripts in Boston collections.” The exhibition overall explains the production and use of books in the Middle Ages and Renaissance (and collection and appreciation since); the separate venues are conceived as three readers’ idealized libraries: for clerics, monks, or nuns, the book-centered monastic life (“Church & Cloister,” Houghton); for a lay user, prayer or professional books (“Pleasure & Piety,” McMullen); for a humanist ruler and patron, during the fifteenth-century birth of the modern book (“Italian Renaissance Books,” Gardner). Pulling it all together, Hamburger jokes, has involved “a cast of thousands.”

One need not be steeped in their scholarship to marvel at the manuscripts’ creation, their survival through their ages, the intellectual heritage they represent—and their riveting beauty.