Blame the smallpox. The outbreak began in the depths of a worse than usual Boston winter, after a worse than usual year, during which the town had buried more souls than it baptized. On January 2, 1764, in tiny type on its last page, alongside advertisements hawking cloth and sugar and rum and tea and indigo and slaves, the Boston Gazette announced the first death from the familiar scourge. “No other Person in Town has that Distemper,” the printers assured readers.

They were wrong, of course. Within weeks, an epidemic took wing. By January 24, Boston was “utterly unsafe,” wrote the painter John Singleton Copley, urging a step-brother to stay clear of the “distresst Town, till its surcumstances are less mallancolly than they are at present.” The province’s legislature, known as the General Court, decamped to the sleepy village of Cambridge. To ensure their safety, and to allow the seamless workings of good governance, the lawmakers would live and work at Harvard College, which had emptied of students for the winter break.

The Court’s business was heady that season, as the legislators formulated a response to the impending Sugar Act, which threatened their crucial trade with the West Indies. New England cod fed the slaves who grew the cane that made the empire rich; New England pine made the barrels in which Caribbean sugar, molasses, and rum were shipped around the Atlantic. That commerce, the province’s governor, Sir Francis Bernard, told his London paymasters, “takes from us what no other markets will receive.” He warned that Parliament’s experiment could come to resemble “the case of the Man whose curiosity (or expectation of extraordinary present gain) killed the Goose who laid him golden eggs.” Perhaps Bernard’s Council debated this very point when it met in the library in Harvard Hall on January 24. Their session continued into the evening, as a blizzard howled, “the severest snow storm I ever remember,” wrote the daughter of Harvard’s president, Edward Holyoke. Before they retired for the night, the councilors, or more likely their servants, banked the hearth, for the gentlemen’s comfort come morning.

The ancient ramshackle building had survived thousands of such nights, during 83 New England winters. This one was the last. Around midnight, a beam beneath the hearth began to smolder. As the blaze caught, the library—at nearly 5,000 volumes, the largest collection of books in North America—became a giant torch. By the time the alarm sounded, Harvard Hall and its priceless contents had to be given up for lost. All hands rushed to save the college’s other four buildings. President Holyoke raced from Wadsworth House in his night shirt, into snow drifts four or five feet high, and “very near lost his life,” his daughter wrote.

A Prospect of the Colleges in Cambridge in New England by William Burgis (ca.1722-1736) shows at left the blended Medieval- and Renaissance-styled Harvard Hall, built in the 1670s, that burned in 1764.

Courtesy of the Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

“All Destroyed!” bellowed the article on the blaze in the Gazette the following week. “We are all real mourners on this occasion,” Holyoke’s daughter said. Copley and his patrons, eastward-facing New Englanders whose fortunes and imaginations centered in London and the ancient world, would have agreed.

But as is often the case, calamity proved the mother of opportunity, not least for Copley himself. The day after the fire, the General Court “cheerfully and unanimously” voted to rebuild Harvard Hall at public expense. Governor Bernard himself designed the new structure, “a much better building” than the old, proclaimed his lieutenant, Thomas Hutchinson. The cornerstone was laid in June, and a phalanx of joiners and bricklayers got to work. A year later, as a fresh round of protests anticipated the crown’s latest effort to tax the American provinces, finish carpentry had begun.

Built of brick and stone and slate, the new Harvard Hall followed the latest principles of architecture: the Enlightenment risen from the rubble of the Elizabethan era. The building’s high-ceilinged main floor featured a grand chamber measuring 36 by 45 feet, a single room as large as most houses of its day. The College needed to line its “new-built” walls. Asked the student author of “Harvardinum Restauraratum,” a poem published in the Boston Gazette: “what are walls unfurnish’d? empty things.”

It is entirely unsurprising that Harvard turned to John Singleton Copley to fill those soaring empty walls. Copley had painted at the College before: a three-quarter-length portrait of an aged and stout Edward Holyoke, perched in the knobby three-legged chair that even today serves as the official seat of Harvard presidents. Just 26 years old when Harvard Hall burned, the young painter had already grown eminent in New England. His brush was busy. Refusing an invitation to take a painting tour of the newly British port of Quebec the following year, Copley explained that he had “a large Room full of Pictures unfinishd, which would ingage me these twelve months, if I did not begin any others.”

On its face, Copley’s rapid rise seems like an American tale. Born poor, to immigrant parents, he had parlayed an ineffable blend of grit, hunger, and talent into a thriving trade. His father, who died when the boy called Jack was very young, left him nothing. Some years later, Jack’s stepfather, the London-born engraver Peter Pelham, started his stepson on a kind of informal apprenticeship—but then he, too, died. Jack was 13 when he inherited the care of his infirm mother, as well as a toddler half-brother, Henry (called Harry). He supported them by painting faces. Like some Horatio Alger creation with a paintbox, Copley bootstrapped his way onto the parlor walls of Boston, Cambridge, Salem, Newport, and Halifax.

Yet his ascent was in fact a British story, more like Fielding’s Tom Jones than Alger’s Ragged Dick. Copley was a child of the empire. Like many of his neighbors, he earned his living from the spoils of its wars. The great global conflict known as the Seven Years War, which began in 1754 and ended just months before the Harvard fire, had made the fortunes of many of the men Copley painted, from imperial bureaucrats like the customs collector who invited him to Quebec, to British officers who paid the young limner to portray them resplendent in scarlet, to merchants like Boston’s Thomas Hancock, who grew rich outfitting ships for the American theater’s northern campaigns. (Hancock’s fleet, fitted with irons in the manner of slavers, deported the Acadians from Nova Scotia.)

Like most American provincials from Newfoundland to Barbados, Copley thought of London as his capital city. Every June, Bostonians celebrated George III’s birthday with fireworks and cannon blasts. Even as Copley and his neighbors remonstrated against the crown’s new taxes, they marked the anniversary of the young king’s coronation. They imported their cloth, and their tea, and their culture from the English metropolis. You could buy The London Magazine at Boston’s London Book Store, on King Street, near its intersection with Queen. The Town House stood there as well, topped by gilded statues of the English lion and the Scottish unicorn, facing the harbor and, somewhere across the ocean, the Thames.

London, a city of more than three-quarters of a million people, with its connoisseurs, drawing schools, and increasingly robust exhibition culture, with its palaces and print shops and even its teeming slums, shimmered at the edges of Copley’s vision. Boston felt small and cramped by comparison: a stagnant town of about 15,000, with too many churches and too little art. Copley had begun to chafe against the confines of a place where paintings could be seen only dimly, in black and white, through “a few prints indiferently exicuted” and the occasional clumsy copy. He called his ailing mother and little brother his “Yowke,” his “Bondage”: ties “of a much more binding nature than the tie of Country.” He dreamed of the day he would “get disengaged from this frosen region” and “take…flight,” seizing as his birthright the British liberty that was the envy of the world.

In the summer of 1765, as the new Harvard Hall inched toward completion, Copley readied a bravura picture of his brother to send to London for exhibition under the auspices of the Society of Artists of Great Britain. The canvas, now known as Boy with a Flying Squirrel, was loaded aboard the Boscawen that September, shortly after Boston mobs tore apart Thomas Hutchinson’s house board by board to protest the Stamp Act. When the grand commissions from Harvard came, Copley was already facing east.

The new portraits would form a triptych, an altarpiece celebrating the patron saints of New England’s higher learning. The Harvard Corporation commissioned two of the three portraits soon after the fire. These presented particular challenges, for both resurrected dead men.

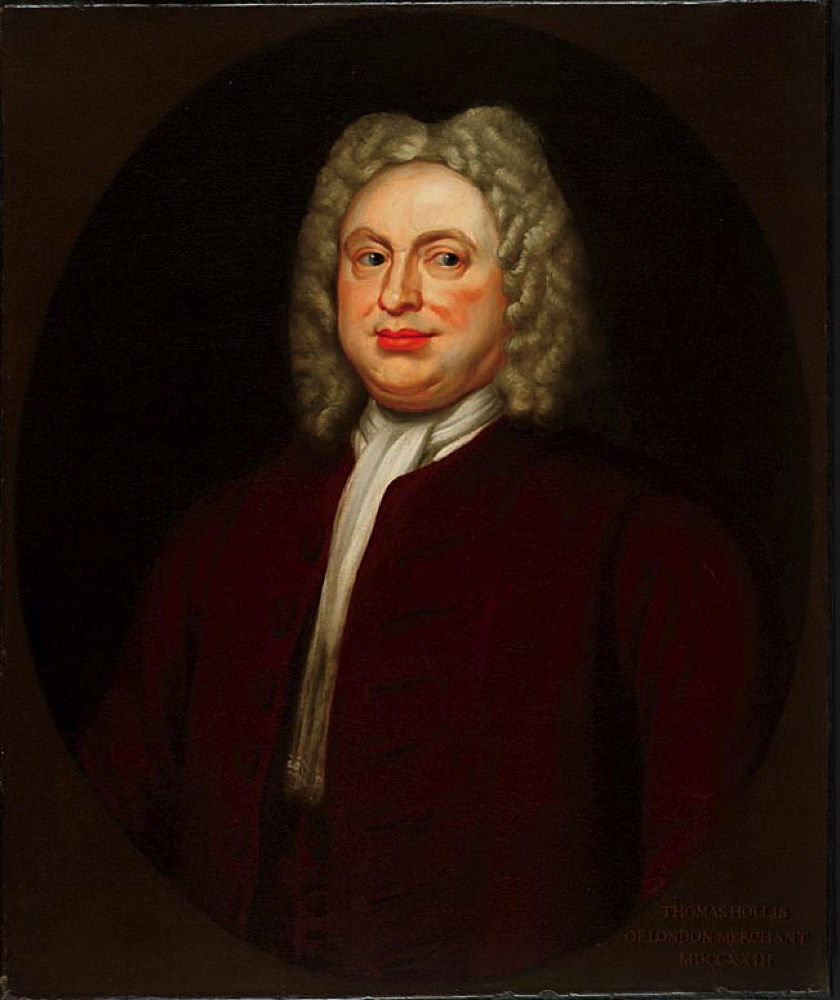

A likeness of Thomas Hollis III (1659-1731), the great benefactor of the College library, had burned with the old Harvard Hall. Hollis had shipped the portrait, by Joseph Highmore, from London in the early 1720s, long before Copley was born. A generation later, in 1751, Peter Pelham had scraped a mezzotint after the “curious picture.” Perhaps 13-year-old Jack Copley had seen the ancient original propped in his family’s modest home on Lindall Row, near the waterfront, while his stepfather translated it onto a copper plate. Pelham promised the College he would take “all due care” of the Highmore painting. The canvas survived another 13 years, but Pelham died a scant three months after completing the print.

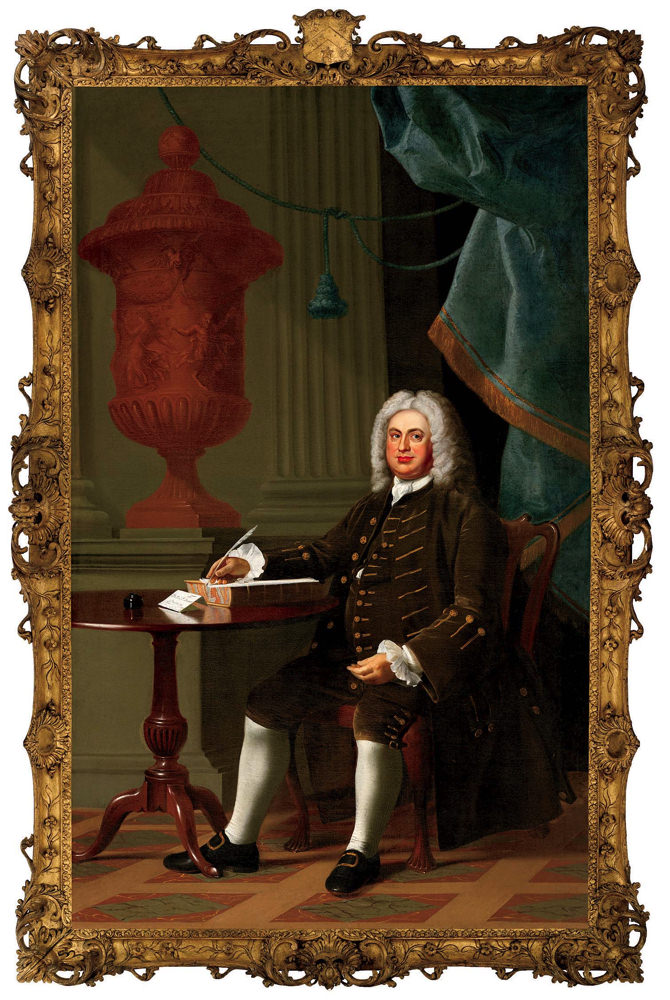

To fulfill his commission for a portrait of Thomas Hollis III (above), Copley had to elaborate significantly upon the much smaller image of Hollis (below), by Giovanni Battista Cipriani, originally sent as a replacement from London.

Harvard University Portrait Collection (H25 and H83); photograph by Harvard Art Museums Imaging Department/©President and Fellows of Harvard College

In 1764, while the embers cooled in the still-snowy Harvard Yard, President Holyoke sought a replacement portrait from Hollis’s great-nephew, who dispatched another image of his ancestor, copied by the Florentine artist Giovanni Battista Cipriani, before the year was out. But that diminutive canvas, a bust-length, depicting Hollis’s head and shoulders, proved unequal to its grand new surround. To hold the wall, it needed to be “drawn at Large,” Holyoke explained. He tapped Copley, whom he described as “a Painter who takes a fine likeness,” to do the job.

The commission to copy a copy would not have especially honored Copley, nor would Holyoke’s compliment have delighted him. A knack for catching a resemblance was a mean talent, mere mimicry, kin to the necessary flattery that tainted portraiture as an art form. “Was it not for preserving the resemblace of perticular persons, painting would not be known in” Boston, the artist lamented shortly thereafter, in his beautiful hand and the characteristically poor spelling that betrayed his lack of formal education. “The people generally regard it no more than any other usefull trade, as they sometimes term it, like that of a Carpenter tailor or shew maker, not as one of the most noble Arts in the World.” He found this state of the arts more than “a little Mortifiing.” Nonetheless, he took the job, whose visibility must have been too much to resist, even for an artist already grooming himself for the London eye.

The work proved as difficult as it was ignoble. Copley must have tacked between the Pelham engraving and the painted copy, neither of which contained even a breath of Hollis’s long-ago life. Even so, Copley found the Cipriani canvas precious enough that he was loath to part with it. He offered to lower his fee if he could keep it, telling Holyoke that Governor Bernard had encouraged him to propose the trade.The president flatly refused, fuming that the governor had overstepped. Bernard “must needs know he had no more power to Dispose of it than the smallest man in the Governmt,” Holyoke said. If Copley “must have more for the new Picture, let it be so.” Better still, the painter might consider the difference a “Gift to the College.” Copley took payment in full.

Was Holyoke pleased with the fruits of the commission? The painting was certainly grand enough. Standing 94 inches tall, Thomas Hollis was the largest picture Copley had ever painted, and only his second attempt at managing a full-length likeness. But it was far from his best work to date. Both the flatness of Pelham’s mezzotint and the lurid palette of the Cipriani, with its too-red lips and its shifty gaze, linger in Copley’s inflated version. He retained the pose of Pelham’s print. But where the page-sized scale of mezzotint forced Pelham to crop his figure close, Copley had some 38 square feet of canvas to cover. The seated Hollis takes up barely half the picture’s height, and Copley struggles to fill the void, with a slate-blue drape framing nothing and a clumsy red urn nearly large enough for the great benefactor to climb into. The figure itself appears literally disjointed, with two right feet. Anatomically, Hollis looks less like a man than a wooden drawing figure. Perhaps the large “layman” that Copley kept in his painting room served as his model. The enormous painting’s most successful passage is a small one: Hollis’s lifelike right hand, which leans on a large folio atop a gleaming mahogany table. An envelope is propped against the book, its address vivid enough that Hollis could have inked it yesterday.

Copley’s patrons expressed frustration with the longueurs of sitting to him; the word “tedious” comes up often in their recollections. Yet to see the failures of Copley’s Hollis is to realize how much of the feeling of life in the painter’s work emerged from the comforts and perhaps especially the discomforts of the studio session. The sheer boredom, the awkward blend of intimacy and deference, the small talk at which Copley was manifestly terrible: these base ingredients combined, alchemically, to produce remarkable illusions of life when Copley had life before him.

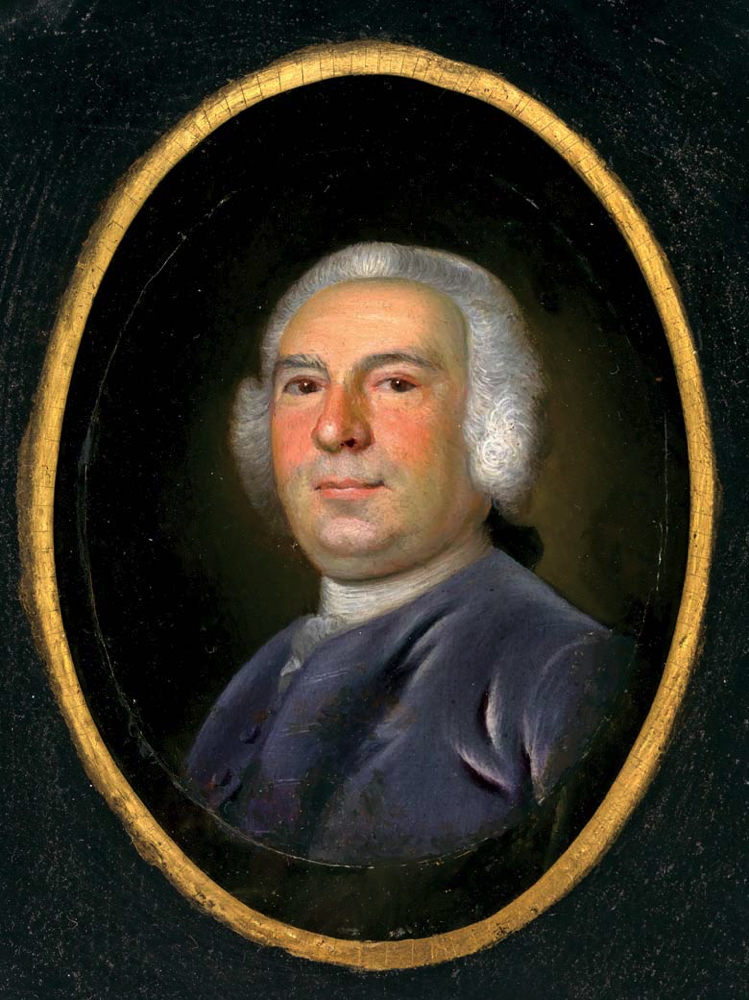

Copley had painted a three-inch miniature of Thomas Hancock (below) in the 1750s, enabling him to update his own work in undertaking the monumental memorial portrait (above) commissioned by Harvard more than a decade later.

Above: Harvard University Portrait Collection (H22 ); photograph by Harvard Art Museums Imaging Department/ ©President and Fellows of Harvard College. Below: National Portrait Gallery/Smithsonian Institution. Conserved with funds from the Smithsonian Women’s Committee

The second commission to emerge, phoenix-like, from the ashes of Harvard Hall at least caught Copley a little closer to home. Thomas Hancock died in early August 1764, after the cornerstone of the new hall was laid but before the roof went on. Agitation against the looming Sugar Act had grown heated with the sticky summer days. The issue of the Gazette announcing Hancock’s passing also announced the publication of a new pamphlet by James Otis, The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved: one of the first sustained statements of American rights. At his death, Hancock was one of the wealthiest men in New England. The newspapers inventoried the “Largeness of his Heart” and the fullness of his purse. Among his many “pious and charitable Donations” was a bequest of £1,000 to Harvard to endow a professorship in “Hebrew and the other Oriental Languages.” In October, a fortnight after the “black day” on which the Sugar Act took effect, the Corporation asked Hancock’s executor and primary beneficiary, his nephew John, “for the Favour of his Picture, in order to have it plac’d in the College.”

As with Hollis, the commission to paint Thomas Hancock required Copley to play the resurrection man. But this time Copley had his own work to draw upon. Hancock had sat to him in the 1750s, when both the middle-aged merchant and the young painter were breaking the frames of their early lives. In two intimate images meant for family display—a pastel portrait and a little copper-backed miniature just over three inches high—Copley depicted Hancock at his high-water mark, masterful and vigorous, buoyed by the fortune he gained supplying his majesty’s army during the Seven Years War. Copley knew that man. He had studied that face.

There can be no question that Thomas Hancock is a more successful picture than the unfortunate Thomas Hollis. Copley has aged Hancock’s face subtly but convincingly. The figure dominates the pictorial space. Its backdrop—a roofless classical temple—emphasizes Hancock’s refinement and his affinity with the virtues of the ancient world.

Beneath its varnished surface, however, Hancock betrays some of the same uncertainty that mars Hollis. Infrared and x-ray analysis by conservators Teri Hensick and Kate Smith at the Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies discloses the depths of Copley’s indecision. He second-guessed nearly every element of the mammoth canvas, from the pose to the drapery to the bric-a-brac in the background. The finished Thomas Hancock stands with both feet firmly planted, his left arm hanging, glove in hand. Lingering traces of earlier versions show the figure partly turned, with legs crossed and arms spread wide, a walking stick held in his right hand. If the hidden layers could be animated, we would see the figure of Thomas Hancock oscillating, as if caught dancing a quadrille.

Copley oscillated, too: between Boston and London, trade and Art, kin and calling. While Hancock and Hollis dried in his painting rooms in the spring of 1766, Portrait of a Boy with a Flying Squirrel hung in London, at the fifth annual exhibition of the Society of Artists. To the throngs who flocked to Spring Gardens to see the show, this was no sepia-tinted assemblage of antiquities, but a thrilling display of contemporary art, with something like the buzz of Art Basel or the Venice Biennale today. An ocean away, Copley waited on whispers caught in letters.

How would the work of this provincial Briton hold up amid the color and clamor of the great metropolis? Copley had no idea. The drought of examples in Boston left him “at a great loss to gess the stile” fashionable in the capital, he wrote that fall. Months passed before he learned how his submission had fared among the cognoscenti, tense months while Hollis and Holyoke were fitted into ornate gilded frames capped with the subjects’ respective coats of arms and installed on the east wall of the soaring new hall. By autumn, Copley’s gargantuan portraits of Hollis and Hancock flanked the fireplace. They made a poorly matched pair: one sitting stiffly in a brown suit with gold braid, the other standing stockily in a coat of murky black, both facing right. Only their checkerboard floors and their matching frames put the two pictures in conversation.

Between the great benefactors, in the prized place over the mantel, hung another large-scale Copley, a three-quarter-length portrait of the governor. There was little politesse around the way Francis Bernard’s portrait claimed that chimneystack. Harvard’s president and fellows did not implore him to sit for it, as they had entreated Hollis’s descendant and Hancock’s legatee. Upending the elaborate protocols that governed the gift economy, Bernard simply came forward and “offer’d to give his Picture to the College.” The Corporation voted unanimously to accept the donation. What choice did they have?

Copley executed Bernard’s portrait first; the embodiment of the governor’s importunate generosity reached Harvard Hall in late 1765, about three months after hundreds of Bostonians had rioted violently against the Stamp Act. Bernard, never beloved, had come to be despised. “I did not apprehend that mine was so much of a military post, as to require my maintaining it ’till I was knocked on the head,” he told Britain’s Board of Trade the following March. “I fear that the Worst is not over,” he said. “I am apprehensive that this Government will not be restored to its authority without some Convulsion.”

Copley’s Francis Bernard probably used the syntax of other images of Crown officials. Perhaps Bernard requested a seated pose, featuring the royal governor’s chair, a throne-like seat that was upholstered in British red. Maybe Bernard was robed in scarlet, too, as many of his predecessors had appeared in their state portraits. Bernard would have wanted to showcase his specific role as architect, as well as his ultimate political authority. Perhaps he held a set of floor plans.

Copley’s Bernard can only be imagined; the painting has long been lost. Before it disappeared, it was attacked, as a stand-in for the governor himself. Bernard proved correct: the worst was not over. In 1768, following yet another wave of protests denouncing yet another group of imperial taxes, the Crown dispatched four regiments of regulars to Boston to keep the peace. Less than a week after the first deployment landed, the painting in Harvard Hall was eviscerated under cover of darkness. Since the building was not a public space, the proxy-murder was likely an inside job. Perhaps the vandals were students, or tutors. Members of the Corporation may have turned a blind eye, or even lent a hand.

The marauders carried tools: a ladder, a razor. They brought a note, a clever caption for their deed. The Journal of the Times, which roused the populace by printing every outrage that fall,described the performance:

From Cambridge we learn, that last evening, the picture of ------- -------, hanging in the college-hall, had a piece cut out of the breast exactly describing a heart, and a note,--that it was a most charitable attempt to deprive him of that part, which a retrospect upon his administration must have rendered exquisitely painful.

Harvard’s own records fail to mention the attack. In late November, nearly two months after the painting was slashed, the President and Fellows voted that the picture be “put into an handsome Frame, the Expence to be defrayed out of the College Treasury.” Then Francis Bernard and his neighbors—the whole Copley triptych—were to be “removed to the philosophy Room” upstairs, to be kept under lock and key.

But first the picture had to be repaired. Somebody contracted with Copley to do the work—either Harvard or the governor himself. (No record survives.) In March, when Bernard’s restored likeness was returned to the College, the Journal of the Times quipped, “Our American limner, Mr. Copley, by the surprising art of his pencil, has actually restored as good a heart as had been taken from it; tho’ upon a near and accurate inspection, it will be found to be no other than a false one.” Bernard’s heartlessness remained obvious. But where did Copley’s heart lie? The Journal’s writer implies that a truly “American” painter might not have done the work quite so well, if indeed he did it at all.

Bernard sailed east that summer, removed from his post, to his considerable relief and enduring mortification. Copley would dither about his own journey out of the provinces for another half decade, chiaroscuro years of professional prosperity, conjugal felicity, and growing political strife. As the ties between the province and the empire further frayed, Copley’s world—a place where loyalties were sketched in infinite shades of gray—slowly dissolved, casualty of an era of black and white. Relationships to earlier patrons, including John Hancock, grew tense and sour. Commissions dried up. Mobs reached his doorstep. In June 1774, days after the laws Bostonians called the Intolerable Acts closed the harbor to trade, Copley sailed for London. He would never return.

John Singleton Copley spent the rest of his long life working to put his Boston style behind him. In London, he climbed the ladder of Art, painting enormous modern-dress histories, moody biblical scenes, and the occasional literary allegory. He portrayed generals, aristocrats, and the occasional royal. His work hung in the Royal Academy of Arts, in the Queen’s palace, and in the great houses of the gentry across Britain. It is hard to imagine that his mind’s eye often wandered back to the triptych in Harvard Hall.

Yet Copley did not want Harvard to forget him. Even before the conflict that came to be known as the American Revolution reached its shocking conclusion, the New England-born painter began sending the College gifts of mezzotints after his great London triumphs. In 1780, while the American War still raged on the seas, he shipped reproductions of Watson and the Shark and The Nativity across the Atlantic to Cambridge. The Harvard Corporation voted him an official thanks, conveyed by the painter’s mother, who had remained behind in war-ravaged Boston. The ensuing years brought a steady trickle of additional prints. The largest cache came posthumously, in 1818, when the painter’s penniless widow, having tried without much success to peddle a box of engravings after her husband’s paintings on the American market, agreed that a set be donated to Harvard. Copley’s son-in-law conveyed 11 prints, with a note telling President John Thornton Kirkland that the group, when added to “those already in your possession will nearly complete a series of the works which have been published of our late celebrated countryman, and form a Copley Gallery.”

For a long time after 1818, the greatest of Copley’s pictures—vast vivid canvases that had filled tents and stirred the English masses—could be seen in the former British colonies only in such black-and-white reproductions: the very conditions Copley himself had once struggled against. Harvard’s prints were kept, with other curiosities, among the collections of the Philosophy Chamber.*

The engravings that comprised Harvard’s “Copley Gallery” remain preternaturally vivid some 200 years after they came to the University: their blacks as rich and inky as the day they were pulled from the press. One seldom sees an eighteenth-century print so pristine as Copley’s Richard Howe, whose wig powder appears fresh enough to dust from the admiral’s shoulders. Such condition suggests that Copley’s gifts were catalogued and then tucked away, acknowledged but not exhibited. And so, to the Boston eye, New England’s greatest early master remained frozen in time, with some of his least successful paintings left to stand in for a brilliant cosmopolitan career.

*Next spring, an exhibition at the Harvard Art Museums will bring together those hidden treasures for the first time in nearly two centuries.