By now, Derek Bok’s two-decade initial stint as Harvard’s president seems only a chapter in his career as a leader in American higher education. The Struggle to Reform Our Colleges (Princeton, $29.95) is the most recent in his long series of distinguished analyses: critiques that credit the value of higher education by treating its flaws seriously and teasing out appropriate remedies. Unfashionably reasonable and soft-spoken, Bok here engages the fundamental irony: at a time when educational attainment matters more than ever, and scholars have gained new insights into effective teaching and learning (and promising technologies to enhance both), the United States has, seemingly, made little progress. Citing the imperative to educate more of the populace, and to do so better, he writes, “It is the need to make progress toward both objectives simultaneously that presents the greatest challenge for America’s colleges” now.

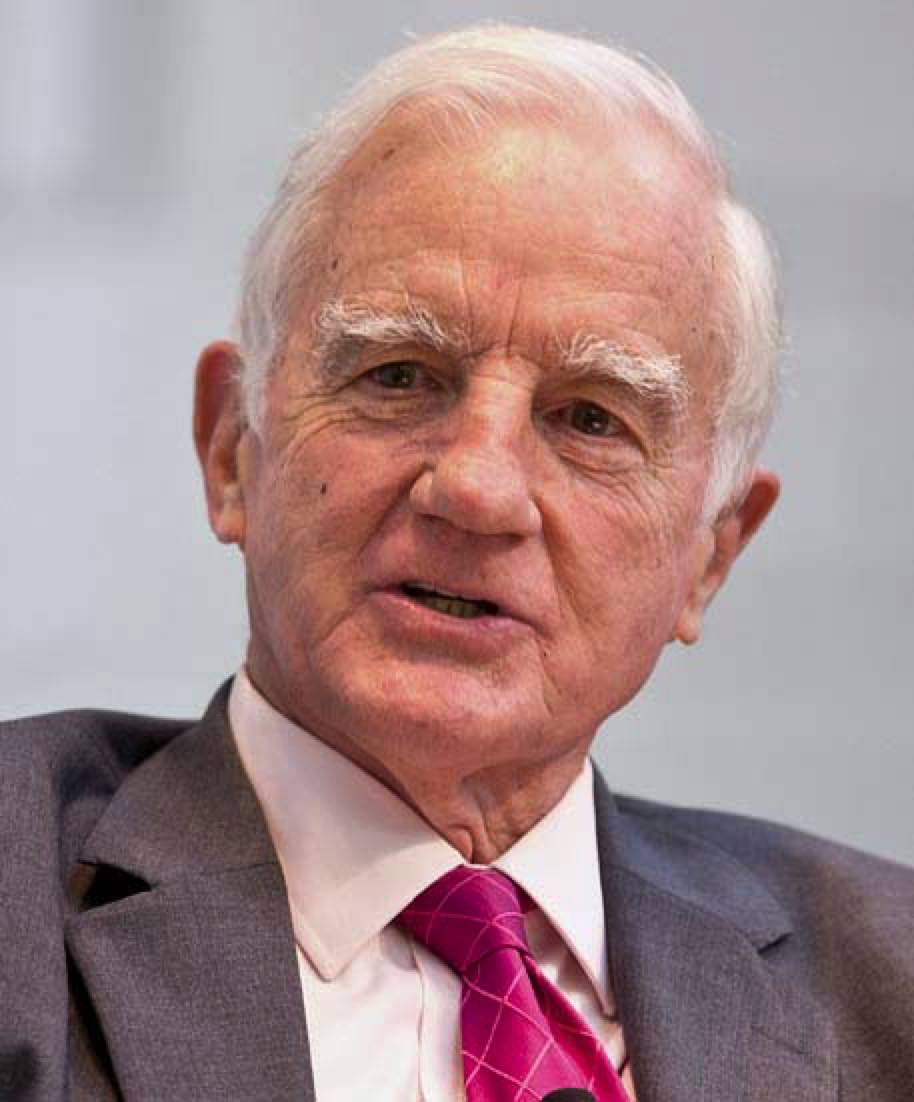

Derek Bok

Photograph by Justin Ide/HPAC

But where to turn when universities themselves are “conservative,” tenure-track faculty members “reluctant” to alter pedagogies and curriculums, adjuncts too hard-pressed and insecure to have a voice, and few presidents eager to pursue major reforms “that could prove to be time-consuming, contentious, and ultimately unsuccessful”? Don’t look to students, Bok says. Their future employers are a source of pressure for justifiable efforts “to evaluate the effects of a college education,” opposition to which is “harder to defend” today. Technology may be promising. Foundations, state and federal government, and accrediting agencies might play constructive roles in raising graduation rates and enhancing quality—but the record is not encouraging.

Bok the educator thus suggests that colleges and universities act as, well, learning institutions: they should test and assess models like Arizona State’s online tutoring as a possible way to enhance the efficacy of remedial courses; or marry financial aid to orientation, mentoring, and peer advising, to see if that boosts college completion. Focus on better graduate education as well, he suggests, so future teachers are better prepared to educate their students; create teaching faculties (rather than beggar adjuncts, who handle so much introductory instruction); put those who teach in charge of revising the curriculum; and get serious about educational research.

Not very tweetable—but an agenda guided by experience, wisdom, and belief in gradual improvement. Bok notes near his conclusion: “many college leaders and their faculties are excessively optimistic about the performance of their own institution.” Just perhaps, a few might listen to one of their own, and begin to assess their performance more realistically.

Carl Wieman

Photograph courtesy of Carl Wieman

In an important, related vein, Nobel laureate Carl Wieman, now professor of physics and of education at Stanford, has brought his scholarly skills to bear on rigorous design and testing of better teaching. Improving How Universities Teach Science (Harvard University Press, $35) helpfully guides readers through discoveries disseminated previously in education journals and forums. Nothing he proposes should be too difficult for any institution that cares about teaching and learning to implement, and the lessons are presented with clarity and force. This is the kind of emerging work Bok hopes to encourage—against the inertial forces Wieman’s scientific colleagues understand so well in their own research.

Finally, just try to be objective about selective college admissions: you will find it impossible to separate your own experience, or hopes for loved ones, from your assessment. At the start of another frenzied admissions season, Rebecca Zwick (formerly of University of California, Santa Barbara, now affiliated with the Educational Testing Service) examines essentially every option and its trade-offs. The result is Who Gets In? (Harvard, $35). Its last sentence says just about everything needed to move “public conversation” about admissions toward a “less rancorous and more productive” place: “The first step is for schools to reveal what is behind the curtain.”