At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Adolf Ziegler won a prize for illustrating the theme of “progress” with a “cabinet of wonders” neatly displaying wax models of human embryos alongside those of frogs, chicks, and electric fish. Comparative developmental anatomy was a thrilling field at the time, and modeling a key research method. Scientists would write descriptive articles and make initial wax figures, sending them to “plastic publishers” like Ziegler and his son Friedrich, who manufactured the copies to promote the research. The Zieglers’ clientele included competing embryologists Ernst Haeckl and Wilhelm His; it was His’s drawings that formed the basis for the Zieglers’ best-selling models of human embryos, exported throughout Europe and to the United States.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

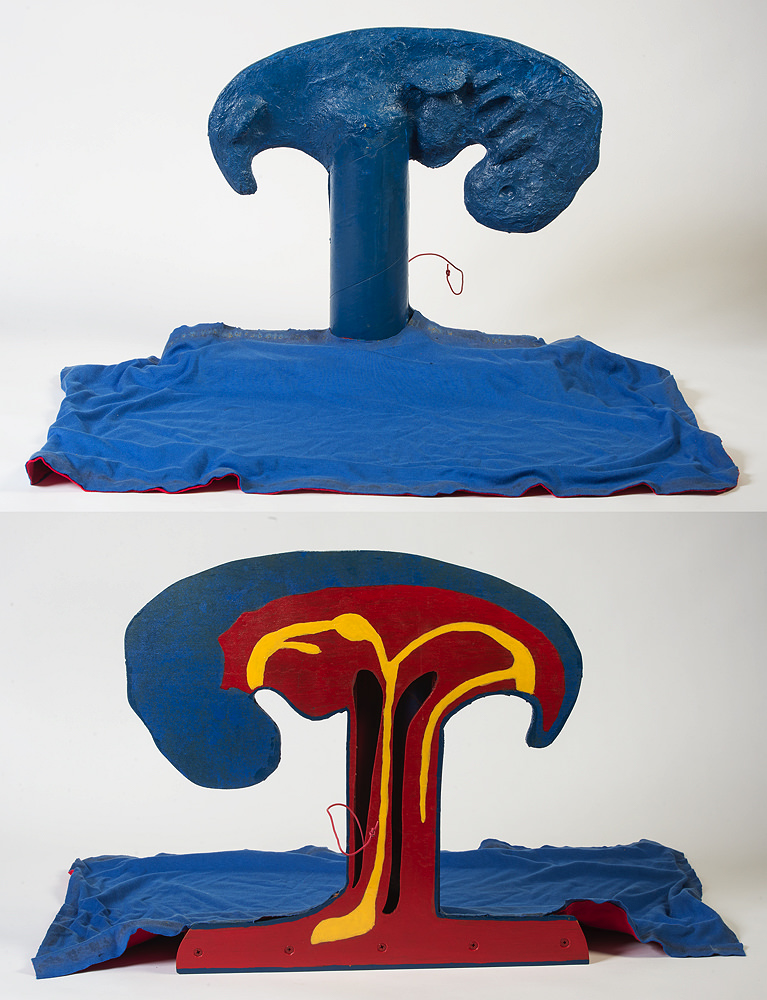

The set above, purchased by Harvard Medical School professor Charles Sedgwick Minot, is only part of the Warren Anatomical Museum’s holdings in embryology. There’s also an edition of Icones Embryonum Humanorum, an atlas-sized 1799 tome by Samuel Thomas Soemmerring, whose fine engravings of the first stage of human life depict a leafy pod peeled open to reveal an embryo like a curled-up bean. Later representations look more geological, as in the specimen above by William Overton Heard, using the “stacked-plate method” considered state of the art in the early twentieth century. Then there are the 3-D stereopticon slides—instead of a scenic vista of Niagara Falls, though, viewers gazed upon a photographic image of a developing embryo, looking like an eruption on a primordial planet. Most recent, and most abstract, are the teaching models used in the late twentieth century by embryology professor Elizabeth “Betty” Hay. The biggest and friendliest is two feet wide: a hard plastic dome, with foam parts inside, painted in cheerful primary colors; fuzzy pom-poms dot its surface.

A teaching model of the human embryo used by HMS professor Elizabeth "Betty" Hay

Photograph by Jim Harrison

Close-up of a Hay teaching model—this one has a hard plastic shell, with a polystyrene pieces inside.

Photograph by Jim Harrison

A painted wood model used by Hay, who also had students make their own models as part of their studies

Photographs by Jim Harrison

In the Ziegler studio, Adolf Ziegler first modeled the embryos free-hand, providing the basis for assistants to make molds and then new waxes.

Photographs by Jim Harrison

The Ziegler series featured eight “stages” of embryonic development; this model shows stage seven.

Photographs by Jim Harrison

A model by Osborne Overton Heard, hired by the Carnegie Institute of Washington in 1913 to make wax and plaster models of embryos. After World War II, he shifted to photographing them.

Photographs by Jim Harrison

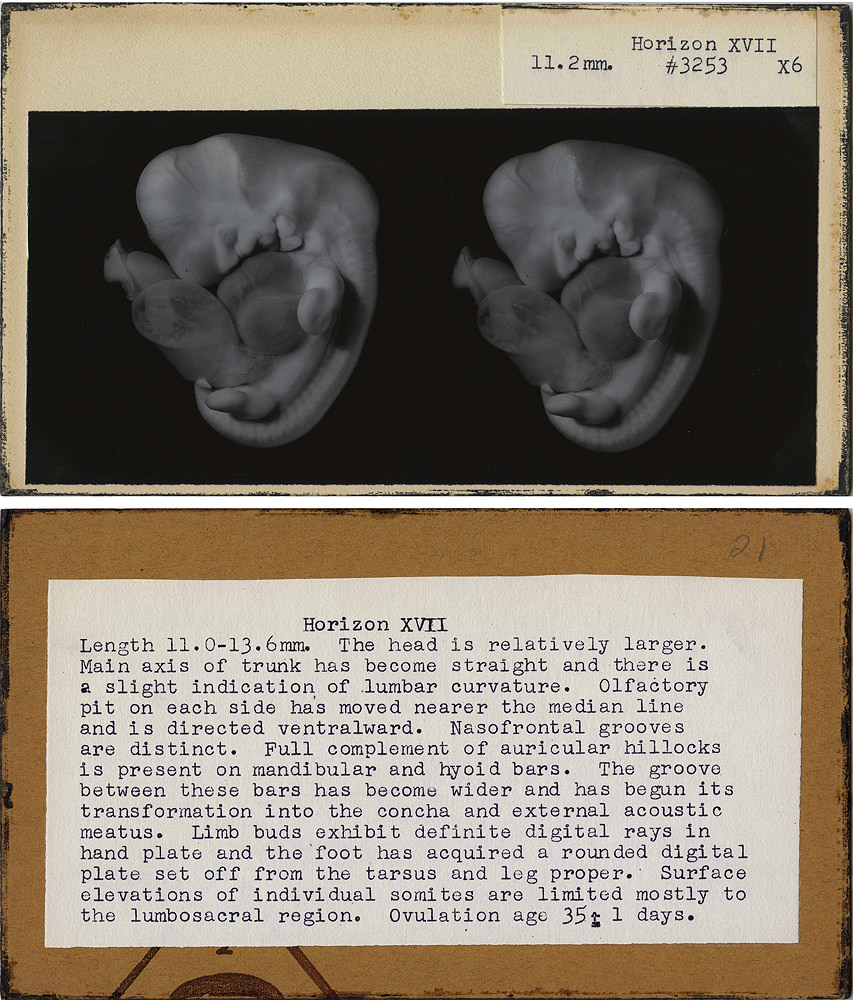

One of a set of stereoscopic slides showing a stage of embryonic development. When inserted into a viewer, the image pops out in 3D.

Courtesy of the Warren Anatomical Museum/Harvard Medical School

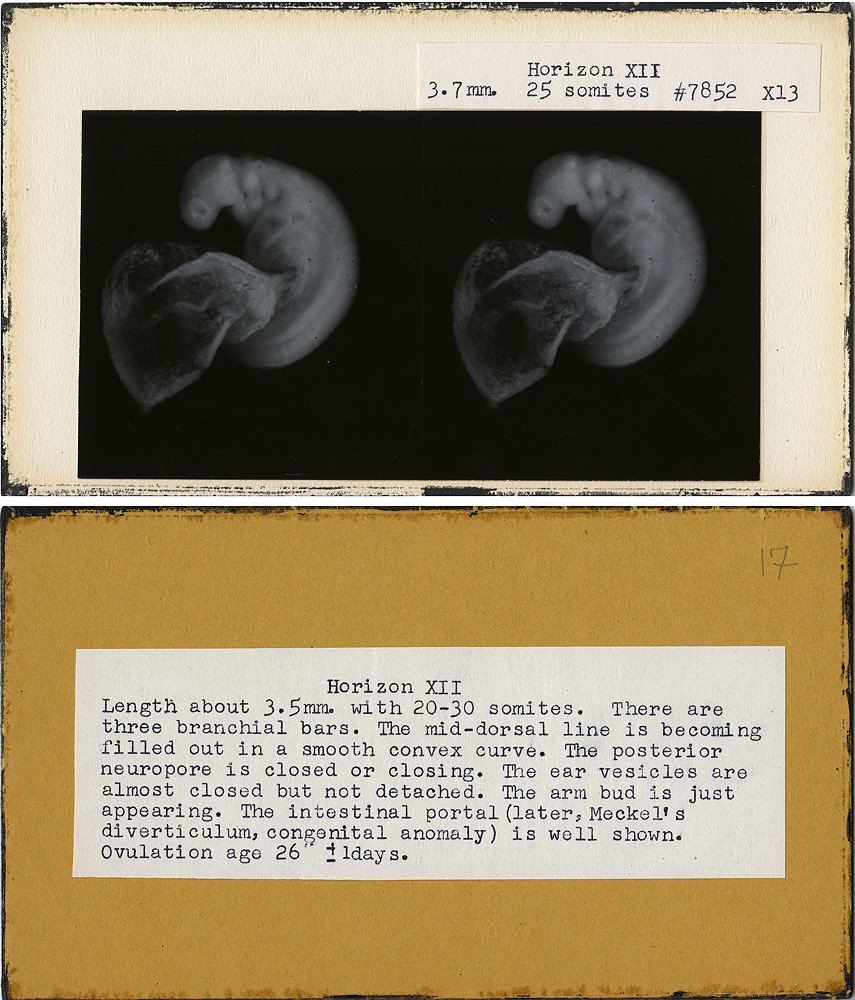

One of a set of stereoscopic slides showing a stage of embryonic development. When inserted into a viewer, the image pops out in 3D.

Courtesy of the Warren Anatomical Museum/Harvard Medical School

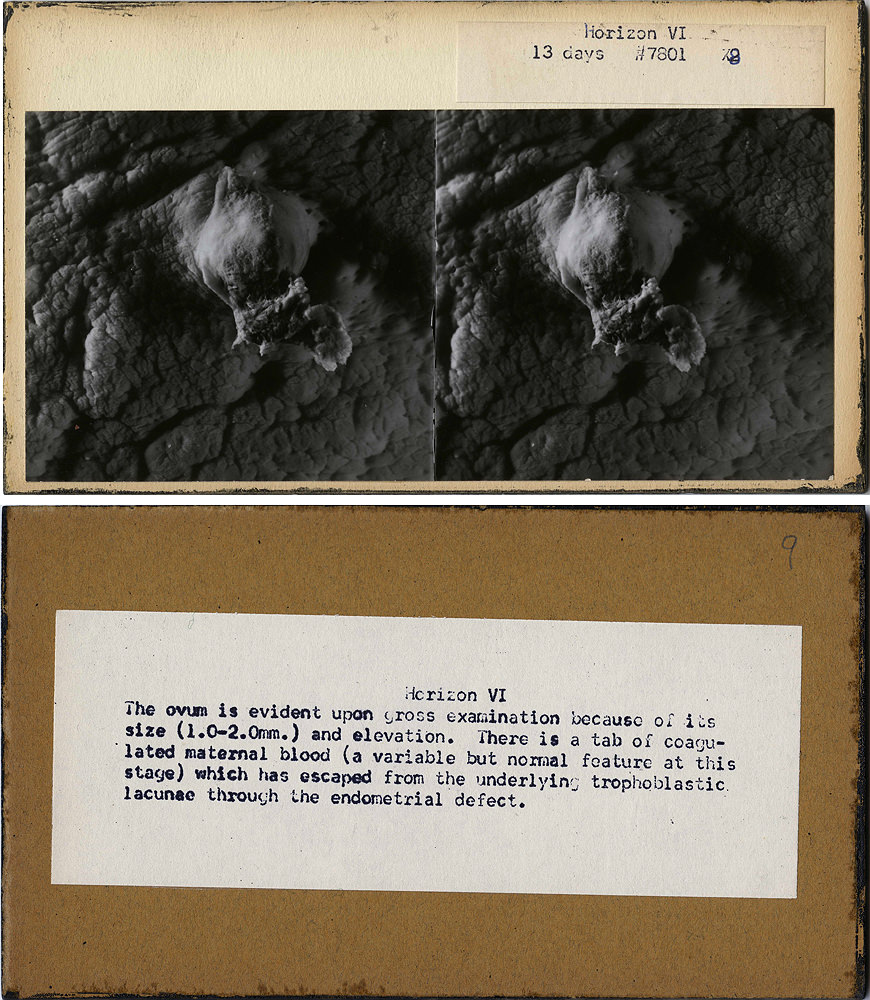

One of a set of stereoscopic slides showing a stage of embryonic development. When inserted into a viewer, the image pops out in 3D.

Courtesy of the Warren Anatomical Museum/Harvard Medical School

The Ziegler embryos in Harvard’s set aren’t especially rare, but they have, in a way, been rendered individual over time. “They’ve all had hard lives,” says Dominic Hall, the musem’s curator. “They’ve been chipped and used and glued together.” Generations of hands have worn features away, or broken them off with rough handling. Across the centuries, models have been thought to “discipline the eye,” helping students learn by touch what can’t easily be seen: making ideas graspable. But they also obscure some phenomena in favor of others. The Zeigler waxes, for example, lack anatomical context. Notably vague: the womb, or even the umbilical cord. They embody a particular idealized notion of life—free-standing and man-made.