Quinn Hoffman, a Harvard freshman on a 13-game hitting streak, stepped up to home plate at Fenway Park.

Batting second in the 2017 Beanpot baseball championship against Boston College, he looked out at the pitcher’s mound, where his father, Trevor Hoffman, had pitched in the 1999 All-Star Game. Beyond the mound, the shortshop was standing where his uncle, Glenn, had played with the Red Sox from 1980 to 1987.

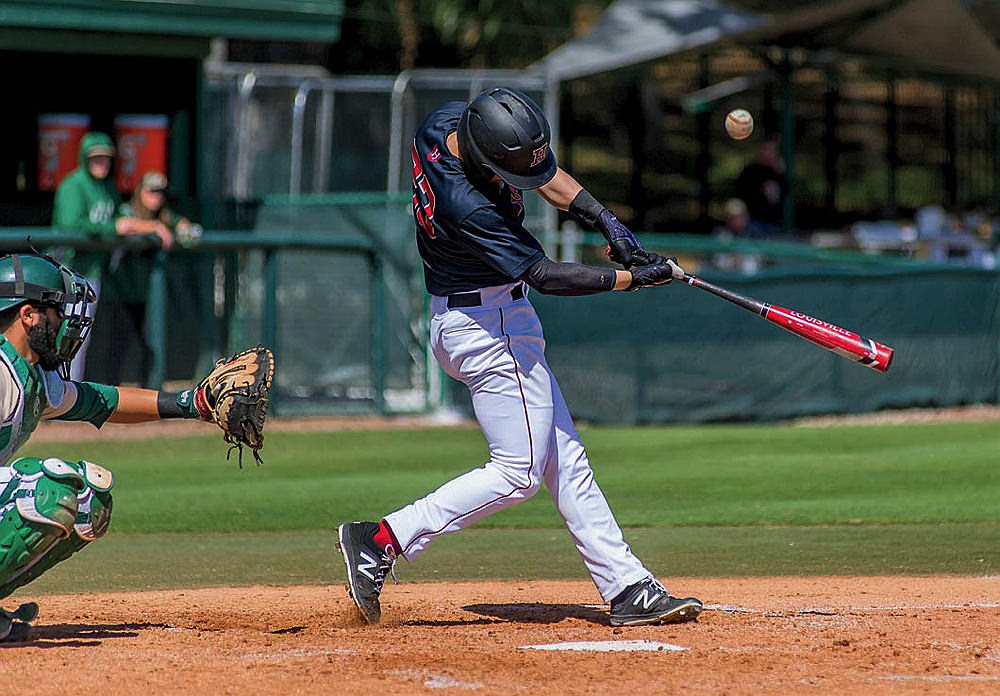

Now, with the first pitch, it was his turn. “I was just able to get a good pitch, and put a good swing on it,” he recalls, “and I didn’t realize I was going to be able to hit it out.” The ball shot off Hoffman’s bat, over left field, toward Fenway’s Green Monster—and cleared the 37-foot wall for his first college home run.

“To be in a place so special to Boston, and to be able to hit a bomb there, is something pretty special,” he recalls. “I was running around the bases with a smile on my face, like I was in Little League again.”

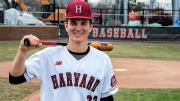

The son and nephew of major-league ballplayers earned his own reputation as a standout last season. Hoffman, the Crimson’s starting second baseman, hit .288 across a team-high 41 games played. He was named Ivy League Rookie of the Week in March and twice made the league Honor Roll in April. “He’s arguably one of the better middle infielders in the area, in the Northeast,” says the Crimson’s coach, Bill Decker. “He’s got electric feet.”

Hoffman had a 14-game hitting streak last year, culminating in a home run at the Beanpot final.

Photograph courtesy of Harvard Athletic Communications

On first meeting, Hoffman seems quiet, but that’s just because he speaks with an even tone. Soon it becomes obvious that he’s eager and chatty about baseball, a quick talker with precise thoughts about his game, who acknowledges the unusual opportunities his family has given him without boasting or self-effacement. “He’s competitive, but he doesn’t do it with a growl,” Decker says. “He’s got that little confident look, not overconfidence.”

This January 24, from Harvard’s Bubble, the winter athletic practice dome inflated within the Stadium, Hoffman called his parents on FaceTime so he could witness a moment his family had awaited for years. Trevor Hoffman, the San Diego Padres’ closer for 15 seasons and the first major-league pitcher to record 600 saves, was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame. In July, Quinn will travel to Cooperstown, New York, with some teammates and possibly some coaches, to see his father inducted into baseball’s pantheon. “It’s everything he’s worked for,” Quinn says. “That’s the top of the game. That’s the peak, the pinnacle.”

A shortshop in high school, Hoffman switched to second base last season because senior Drew Reid held the starting job at short. “When you’re a shortstop, you’re more fluid, and throwing the baseball is more one motion,” he says. “As a second baseman, you have more time. You don’t have to be as fast with your throws, so you’re able to be more relaxed.”

The change also helped Hoffman focus more on batting, which paid off in his 14-game hitting streak, from April 1 to 19, culminating in his 2-for-2 performance at the plate in the rain-shortened Beanpot game (which Harvard lost to Boston College, 3-2, in four and a half innings). Hoffman says his timing and his mental game each played a role. “My foot was down early. I was seeing the pitches really well. Things started to click,” he recalls. “Midway through the season, I was able to forget my bad at-bats and remember the good ones.”

Playing for Harvard, Hoffman is starting to fulfill the promise he showed very early, growing up in a major-league-ball-playing family. “I was given a ball, and I was given a bat, when I was…I can’t even remember,” he says. “It was handed down to me. It’s kind of in my blood.”

When he was six, his dad took him to the Padres’ Petco Park, and, trusting his skills, left him in the outfield during batting practice. Someone hit a line drive that came straight toward him. His father “freaked out,” Hoffman recounts. “I don’t remember it—he tells me the story about it—but I guess I caught it.”

Even as a kid, Hoffman knew he wanted to play his uncle’s old position. “I’ve always wanted to be a shortstop,” he says. “I kept playing infield, enjoyed it, being able to get my uniform dirty and dive.” He watched his dad’s teammates play short and second base, soaking up their mechanics, their footwork, their arm action, how they turned double plays. Meanwhile, he watched his father—a bullpen leader famous for entering games in late innings to AC/DC’s “Hells Bells”—lead by example with his work ethic. “[He’d be] showing guys, ‘Hey, we’re getting up early, going to work out, going to run,” he recalls.

Trevor Hoffman pitched for the Padres from 1993 to 2008, then ended his career with two seasons in Milwaukee. His older brother, Glenn, has been the Padres’ third base coach since 2006. While in high school, Quinn spent a couple of weekends a year with his uncle at the Padres’ spring training in Peoria, Arizona, shagging fly balls during batting practice and taking part in infield drills. “He gave me a couple tips here and there: try to stay underneath the ball, be quick with your feet, let your hands do the work,” Hoffman recalls.

He was a standout as the shortstop at Cathedral Catholic High School in San Diego. His senior year, he was team captain and most valuable player. With younger brother Wyatt starting next to him at second base, the team won the California Interscholastic Federation’s San Diego Section Championship, the top accomplishment for a high-school team in the metro area. The Padres picked him in the thirty-sixth round of the 2016 draft (a move the San Diego Union-Tribune described as a “courtesy” to his father). “As a kid you dream of getting drafted by a pro team,” he says. “It was surreal. I was in shock. I was also committed to Harvard, so I couldn’t go wrong with my decision.”

The sophomore sociology major wants to follow his dad and uncle into professional baseball, either on the field or off. “If I’m not able to play,” he says, “I’d like to do something that involves baseball, inside the game.”

Meanwhile, he’s been recovering from off-season shoulder surgery, undergoing twice-weekly physical therapy. As of press time, he was hoping to return to the Crimson lineup sometime this spring. When he does, he’ll likely become the starting shortstop. “As soon as he’s healthy, we become a better ball club,” says Decker.