Dean Duo

As the Harvard presidency transitions from Drew Faust to Lawrence S. Bacow, two deanships were filled by appointments announced late in spring term.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Paul professor of constitutional law and professor of history, has been appointed dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, effective July 1. She succeeds Jones professor of American studies Lizabeth Cohen, who returns to research and teaching, following seven years leading the institute.

Brown-Nagin, who earned her J.D. at Yale and her Ph.D. at Duke, came to Harvard from the University of Virginia in 2012. Her academic footings, in a professional school and the liberal arts, mirror the institute’s University-wide interests and programs—and she has direct experience at Radcliffe as well, as a fellow in the 2016-2017 academic year. She is currently faculty director of the law school’s Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice, bridging scholarship and practice. Her 2011 book, Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement, won the Bancroft Prize, conferred on outstanding works on U.S. history, and she is now working on a life of Constance Baker Motley, the first African-American female federal judge. A full profile is available here.

At the Graduate School of Education, Bridget Terry Long, Saris professor of education and economics, has been appointed dean as of July 1, succeeding James E. Ryan, president-elect of the University of Virginia.

Long earned her doctorate at Harvard and began teaching at the school in 2000; she served as academic dean from 2013 to 2017. Her research focuses on the transition from high school to college, including such factors as college preparation and financial aid. She is a research associate of the National Bureau of Economic Research, and also serves on the board of directors of Buckingham Browne & Nichols School in Cambridge.

As president-elect Lawrence S. Bacow emphasizes the importance of higher education in face of public criticism and partisan challenges (see “Continuity and Change,” May-June, page 14), Long’s expertise, and Bacow’s familiarity with her work, may be especially pertinent. In a statement accompanying the news, he said, “I came to know Bridget Terry Long during my time in residence at the Graduate School of Education. We share a common interest and passion for improving access to higher education for talented students from families of limited means. I look forward to working closely with her to achieve this goal and to advancing the important work of the School.” A more detailed report appears here.

Graduate Student Union

In April, Harvard graduate students voted 1,931-1,523 in favor of forming a labor union, ending a protracted, fiercely contested debate over unionization across the University. Provost Alan Garber announced in early May that Harvard “is prepared to begin good-faith negotiations” with the union—a notable break from the precedent set by Columbia, Yale, and the University of Chicago, which have refused to bargain with the victorious student unions elected on their respective campuses.

The Harvard Graduate Student Union-United Auto Workers (HGSU-UAW) covers a bargaining unit of about 5,000 research and teaching assistants from across Harvard’s schools, including the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, the professional schools, and the College. This election was Harvard’s second: graduate students previously voted on unionizing in November 2016, an election that turned out to be inconclusive. A majority of students then voted against unionizing, but after more than a year of legal battles that reached the federal National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in Washington, Harvard was ordered to hold a second election. The University had failed to provide a complete list of eligible voters prior to the election, creating confusion about eligibility, the NLRB found.

HGSU-UAW was notably better organized in the weeks leading up to this election than the previous one: student organizers at the Law School and other professional schools, not just Ph.D. candidates, rallied support among their peers, and the union’s social-media messaging stressed the benefits of unionizing for students across Harvard. Still, at the vote count at the Boston NLRB on April 20, representatives from HGSU-UAW were ecstatic and appeared, perhaps, a bit floored by their victory.

Meanwhile, some universities are seeking to reverse the NLRB’s position on the union rights of graduate students. The NLRB ruled in August 2016 that graduate students are university employees and thus have collective bargaining rights. The agency has reversed its position on that matter twice since 2000, and, if a relevant case appears before it, the Trump-era NLRB is thought likely to do so again. For further details, see this report.

Final-club Recognition

The College has announced that unrecognized single-gender social organizations (USGSOs; final clubs and Greek organizations) seeking to gain recognition and thus avoid the sanctioning of their members, will have to file a gender breakdown of their membership and their governing documents, among other steps.

Harvard policy now prohibits students who have belonged to USGSOs within the previous year from receiving the required College endorsement for certain fellowships or from holding leadership positions in recognized student organizations or athletic teams. To designate previously unrecognized social clubs, the new Dean of Students Office (DSO; described here) will create a new category, Recognized Student Organizations (RSOs).

To become an RSO with “interim” recognition (lasting for one academic year), final clubs will need to submit not only their gender breakdown (which need not include information that could identify members), but also a public affirmation of gender-inclusive membership and recruitment policies; the appointment of an official who will be a liaison between the club and the College; documentation of certain required trainings for its board members, including coverage of sexual-assault and anti-hazing prevention; and information about local autonomy and governance. (The latter requirement may not mesh with some final clubs’ graduate boards, composed of alumni members with power over club policies and membership.) Clubs won’t have to achieve any quota or specific gender breakdown.

To receive full recognition after the one-year interim period, RSOs will also need to provide their recruitment schedules to the DSO, and to offer all their members training in areas like anti-hazing and sexual-assault prevention. A third tier, “recognition with distinction,” will be reserved for organizations that have “achieved a standard of excellence” and have recruitment policies that promote diversity.

This recognition process, announced by dean of students Katie O’Dair in May, is the second step in the College’s effort to enforce its sanctions. The rules for individual students were laid out this past March. Undergraduates will not have to make affirmative statements that they don’t belong to a USGSO, and the College will not accept anonymous reports of policy violations or actively seek out students in violation of the policy. For further details, see here.

Faculty Diversity

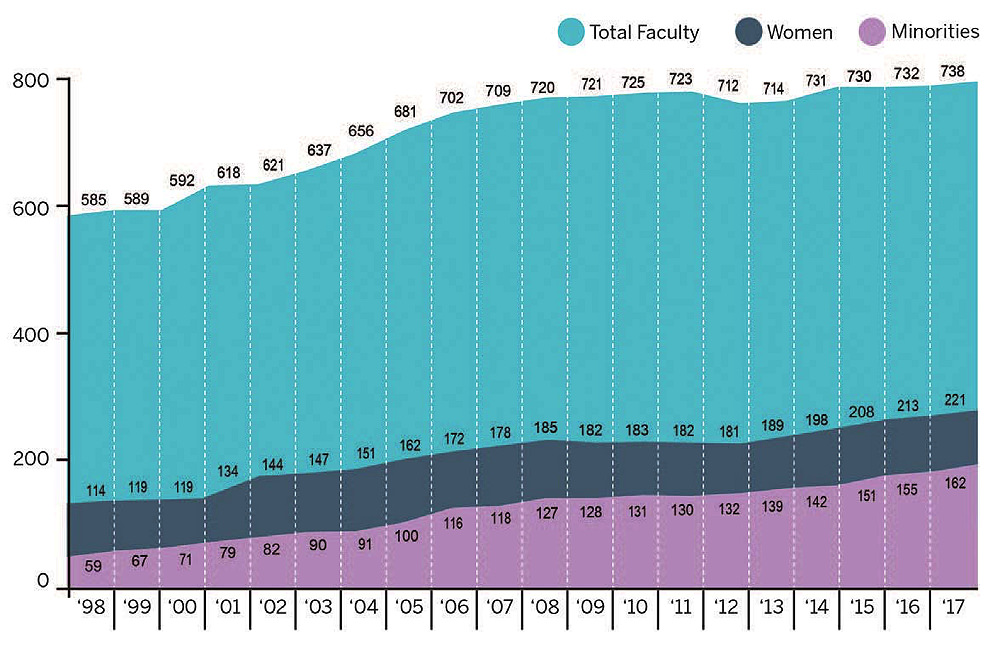

For the last decade, the University has tracked its progress in recruiting and retaining faculty members who can make it more inclusive in terms of race and gender. According to the newest annual faculty-diversity report, published April 12 by the office of Judith Singer, senior vice provost for faculty development and diversity, 27 percent of tenured faculty are women as of last September—up from 26 percent last year and 21 percent in 2008. Underrepresented minorities (African Americans, Latinos, and Native Americans) make up 8 percent of tenured faculty—unchanged from last year and up from 5 percent a decade ago.

Ladder faculty counts in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, 1998 to 2017

Courtesy of the Senior Vice Provost for Faculty Development & Diversity

These gains may sound small, but because turnover in faculty ranks is extremely slow, changes in composition occur in small increments each year. Of the 14 FAS faculty members who were reviewed internally for tenure in 2016-2017, nine were promoted, including six of nine men and three of five women. In the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS), women represent 27 percent of tenured and 43 percent of tenure-track faculty members; Asian Americans make up 12 percent of tenured and 21 percent of tenure-track faculty. Especially noteworthy is the University’s persistent lack of black and Latino faculty members—just 9 percent of both tenured and tenure-track faculty in FAS belong to these underrepresented minorities, pointing to a worrying pipeline problem. The report stresses the need to develop minority scholars much earlier: for example, through undergraduate research programs that promote student-faculty relationships and interest in academic careers.

For the first time, men and women are represented equally on the tenure track of the FAS sciences division, the report shows. But in December, a study led by Elena Kramer, chair of organismic and evolutionary biology, and Radhika Nagpal, professor of computer science, found that in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, only 69 percent of female junior professors stayed long enough to come up for tenure review, compared to 84 percent of men. The report attributed the disparity not only to implicit bias against women, “institutional and structural barriers, such as problematic maternal/paternal leave policies, inadequate infant/early childcare on campus, and poor support for dual academic career couples that is substantially behind our peer institutions,” but also to “persistent culture problems” in certain departments, including explicit sexism. To improve the retention of women, the University has announced that it will open a seventh childcare center in Allston in 2021—a year after the new science and engineering complex opens there. Read more on this subject here.