“You should have a record.” That sentence dropped like a hammer inside the meeting room where Khalil Gibran Muhammad, then 21 years old, was sitting across the table from a Philadelphia police-union lawyer, answering questions about the day he’d briefly been arrested.

This was late May 1993. Several weeks earlier, Muhammad and a few other University of Pennsylvania students had organized a demonstration, with plans to seize copies of the student newspaper from distribution boxes: a last-ditch protest against a series of racially provocative op-eds that had roiled the campus for much of the school year. When Muhammad, dressed all in black, began stuffing newspapers into a trash bag a few minutes after six in the morning, he was cuffed and taken to a police station in the back of a patrol car. A couple of hours later, the police figured out what was going on (“There were reports of students running around with newspapers all over campus,” Muhammad says), and he and the others were released without charges. But because an officer had hit him on the legs with a baton during the arrest, and he was a student, a disciplinary process lurched into motion, to determine if the officer had overreacted. The final step was the meeting with the police-union attorney.

Penn’s general counsel, representing Muhammad, had warned him not to lose his cool: don’t show any emotion, don’t react, just tell your story. So that’s what he did, he says, “And it drove the other lawyer bananas.” Finally, in frustration, the man banged his fist on the table and said, “You should have a record.” It felt like a mask had slipped. Muhammad was a recent graduate of an Ivy League university. He’d just started a job at the accounting firm Deloitte & Touche. He was well-spoken and self-assured and steady and genial. And also, he was black. “And it just hit me in that moment,” he says, “what he was really saying.”

The “Public Transcript” of Urban America

The link between race and crime is one of the most potent and enduring ideas in the modern American imagination. It shapes public policies and social attitudes; it affects what Americans see when they look at one other. In education, housing, jobs, recreation, and other realms of city life, the idea of black criminality has altered what Muhammad—now professor of history, race, and public policy at the Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) and Murray professor at the Radcliffe Institute—calls the “public transcript” of the modern urban world.

The Daily Pennsylvanian account of the incident that led to Muhammad's meeting with a police lawyer.

Image courtesy of the The Daily Pennsylvanian

But it is not eternal. It can be traced to a particular moment in history, and in The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern America, the 2010 book that made his name as a historian, Muhammad traced the idea of black criminality to the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, a period of enormous, rapid social change in the United States. Slavery had ended, legally transforming a population of four million from property into people, and segregation was taking hold. Northern cities—for Condemnation is a Northern story—were industrializing and expanding, absorbing vast waves of immigrants from Europe and, starting in the 1910s, an increasing tide of African Americans from the Jim Crow South.

Simultaneously, statistics was emerging as an essential tool in the social sciences. This happened at a moment when Northern whites, whose antebellum knowledge of black people had been mostly ad hoc and anecdotal, were anxiously wondering what kind of citizens and neighbors these formerly enslaved people might become. They found it, Muhammad says, in the 1890 census, the first to measure African-American demographics a full generation after the Civil War. Although blacks were 12 percent of the country’s population, they accounted for 30 percent of its prison inmates. Racially motivated policing and surveillance were common by the 1890s, but white social scientists took the raw data as objective and incontrovertible. For years, “race experts” like Harvard scientist Nathaniel Shaler had warned of the havoc African Americans would wreak on society. The 1890 census seemed to prove them right. “From this moment forward,” Muhammad wrote, “notions about blacks as criminals materialized in national debates about the fundamental racial and cultural differences” between blacks and whites. Black criminality became a widely accepted justification for prejudice, discrimination, and “racial violence as an instrument of public safety.”

This was a groundbreaking finding. It had long been thought that the 1960s, the decade that produced Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s The Negro Family, was the moment when America’s statistical discourse about black dysfunctionality took root. “When Condemnation came out, it was huge,” says Elizabeth Hinton, assistant professor in history and African and African American studies (see Harvard Portrait, March-April 2017, page 19). Muhammad’s book arrived amid a surge of new scholarship on race, crime, and mass incarceration—most famously Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow—that has altered the national conversation. But most of those books were written by sociologists and legal scholars. “Khalil’s book was really the first by a historian that opened up these questions about the criminalization of people of color in the United States, and about how these disparate rates of incarceration should be understood,” says Hinton, whose own book, From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime, picks up the story a few decades after Condemnation leaves off. “You can’t really write about crime in the United States now without citing Khalil’s book or engaging with the ideas in it.”

Condemnation appeared three months after The New Jim Crow. Michelle Alexander remembers reading it and recognizing a kindred scholar on a similar path—and realizing that the path stretched back much further than she’d known. “In my work, I was trying to demonstrate that our nation has this pattern, this habit of rebirthing these monstrous systems of racial and social control and trotting out the same racial stereotypes to rationalize each one,” Alexander says. “Khalil showed that we’ve been having those same debates since Reconstruction.” She adds, “I wish I’d had the benefit of his work when I wrote my own.”

For white immigrants, however, history unfolded differently. This is the devastating contrast at the heart of Condemnation. Like the African Americans arriving in cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York, newcomers from Italy, Ireland, and other parts of Europe were mostly poor and illiterate, discriminated against and labeled as dangerous. And like African Americans, they also had disproportionately high rates of disease, suicide—and crime. But Progressive era reformers, Muhammad wrote, interpreted immigrants’ dire statistics as consequences of industrialization and structural inequalities, rather than a fixed, congenital fault. In black neighborhoods, where residents were left to solve social ills largely on their own, violence begat more violence. But in immigrant neighborhoods, violence begat settlement houses, recreation centers, libraries, and playgrounds, as reformers strove to open pathways of rehabilitation and upward mobility.

In the preface to a 1903 study of immigrant life in Boston, Harvard economist William Ripley described the “horde” landing on New England’s shores as ignorant, lawless, and prone to crime—but hampered by nurture, not nature. “They are fellow passengers on our ship of state,” he wrote. In 1909, Ripley cautioned against tarring whole immigrant groups with the moral failures of individuals: do “not allow the crime of one Italian…to weigh for any more than the crime of an American.” African Americans were not part of his formulation.

That same racial calculus drove pioneering statistician Frederick L. Hoffman, a fascinating and malign character who looms large in Condemnation and whose effect on the country’s race debate remains profound. His 1896 book Race Traits and Tendencies of the American Negro, the first full-length analysis of the 1890 census, presented black criminality as immune to improvement. In Condemnation, Muhammad stated, “Hoffman wrote crime into race.”

The book ends in the 1930s, when the annual federal Uniform Crime Reports began to standardize arrest statistics. Muhammad chronicled the sustained efforts of scholars and activists like W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, and Ida B. Wells—and the generation of black social scientists who followed them, plus a few prominent white experts and blue-ribbon commission reports—to challenge the authority of racial crime statistics. In fact, from the earliest days of Hoffman’s obsession with race data, other voices pushed back against his conclusions. One was M.V. Ball, a prison doctor in 1890s Philadelphia who saw impoverished childhoods and hard living conditions, not racial degeneracy, in elevated African-American crime and disease rates. Hoffman, Ball said, had neglected the “sociologic factor.”

“But Hoffman hardly looked back,” Muhammad wrote. And by and large, the country went with him.

“A Robust Sense of Historical Literacy”

The success of Condemnation was immediate and intense. The book won the 2011 John Hope Franklin Publication Prize, awarded each year to the best book in American studies, and Muhammad, then a history professor at Indiana University, suddenly found himself sought after as a public speaker and writer. In op-eds for The New York Times, The Guardian, The Nation, Newsweek, National Public Radio, and other outlets, he discusses present-day mass incarceration and criminal justice, police violence, the Black Lives Matter movement, the racial implications of Donald Trump’s ascendance, the rhetorical sleight of hand in decrying “black-on-black crime.” During a 2012 interview with public television’s Bill Moyers, Muhammad declared New York City’s stop-and-frisk policy—then still in its heyday—a form of racial surveillance and control whose roots reached back to the “black codes” of a century ago: “It allows law enforcement, in this city—just like it did in the 1870s in Alabama—to have the widest berth of discretion to challenge a person, a black male on the streets, to ask them, ‘Where are you going? And do you belong here?’”

Now 46, slim and square-shouldered, Muhammad exudes a perpetual low-key intensity, like an engine always in gear. Candid—sometimes blunt—and carefully precise, he is also warm and funny, with a cagey smile that can make a listener feel simultaneously embraced and examined. In 2016, he came to Harvard, the historian’s first foray into teaching policy. “If we’re sending people out into the world in a deliberate and intentional way, to be servants of change, to have the charge of governing a social compact of civic engagement and civic responsibility,” he explains, “then how could I not want to touch these people?” It’s important, he adds, for HKS graduates to be able to bring “a robust sense of historical literacy” to their work.

After a year’s sabbatical, he taught his first class last fall, “Race, Inequality, and American Democracy.” The students seemed hungry for the subject, he says. In fact, demand was so high that enrollment, originally capped at 30, had to be doubled, and for three months, students crammed into a Brattle Street classroom for discussions on education, economics, American values, criminal justice, urban policy. Roughly half the students were nonwhite—“The highest diversity you’ll see in a class at HKS,” says Matt McDole, one enrollee—and discussions were spirited and emotional, rigorous and sometimes raw. Students asked searching questions and wrestled with knotty, complex readings. They drew arguments from their own lives and work experiences. Late in the semester, one student, a police officer, raised his hand and hesitantly recited the murder rates among African Americans in several cities. The numbers were ghastly. Tugging the brim of his baseball cap and hardening his voice, he confessed unease about the contrast between what the course was teaching and what he saw on the streets: law enforcement couldn’t simply ignore those statistics, could it? “And I’m black,” he added. “Trust me, I don’t want these numbers to be true.”

Muhammad sees stop-and-frisk policies as a form of racial control rooted in the Southern "black codes" that restricted African Americans' freedom after the Civil War.

Photograph by Mark Bonifacio/NY Daily News via Getty Images

Muhammad opened the floor to classmate responses, and the conversation ranged widely from there. But if the historian had been answering his student himself, he said later, he would have pointed, in part, to the early twentieth century, when violence in immigrant and white communities prompted not only playgrounds and settlement houses, but police reforms that made law enforcement more like social work. All this, he says, amounted to an anti-violence strategy focused on including white immigrants in American society and encouraging their belief in the social contract. Meanwhile, African Americans faced much of the same violence, but “those strategies for investment in the African American community to be part of America, to be part of what would become the New Deal, to be subject to the same kind of police reform that whites had—that did not happen.” Policing in black neighborhoods remained harsh, often abusive, and alienating, he says. In many instances, up to the present day, he adds, police became “the light that lights the powder keg of racial violence.”

Throughout the semester, as the class took on contemporary social problems, Muhammad kept nudging the students back toward the history they were learning, and its ability to broaden their imaginations beyond the limits of their empirical experience. On the last day of class, amid a discussion about desegregation in schools and policing, he gave them one more push. “Why would we retreat into the immediacy of today, when a wider set of choices informed by a sense of history is always there for us?” he said. “It’s always right there.” In a truly integrated education system, he said, it becomes impossible to choose one school over another as “more deserving” of public investment; desegregated policing means one set of practices for both white and black neighborhoods. That’s what policy should reach for, he said—“That’s what desegregation means.” It was striking how radical the idea sounded when he said it out loud. “This is the difficulty you all face,” he continued. “You will work in systems and institutions, and those systems and institutions are built to do what they do,” which perpetuates the status quo. “And the question is, can they be fundamentally changed to do something else?”

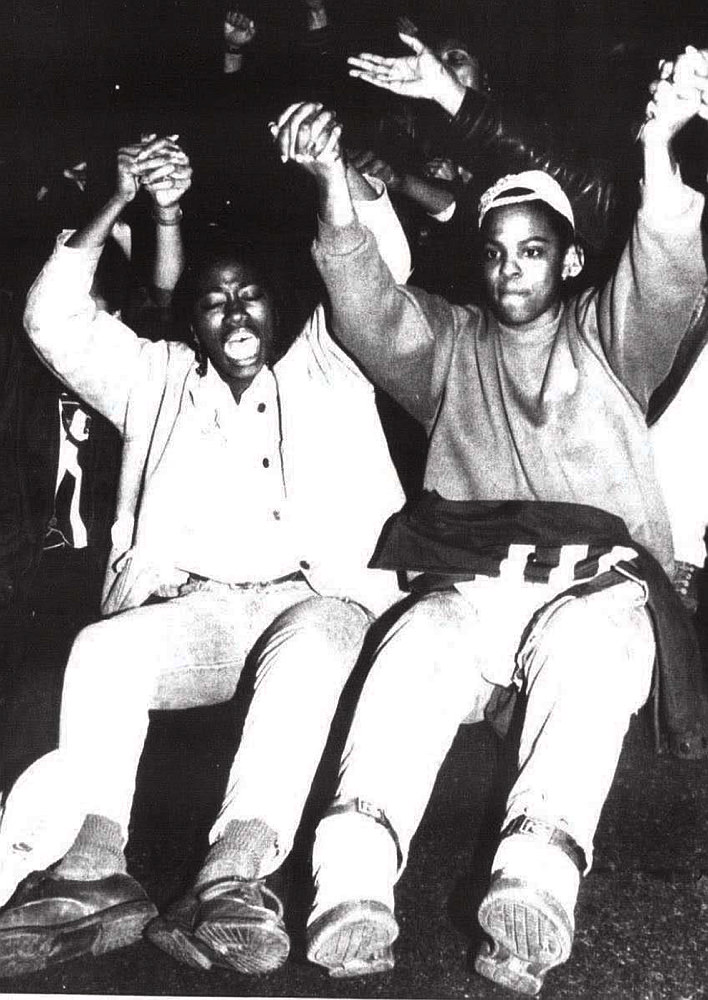

The 1992 acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers in the Rodney King beating sparked protests at the University of Pennsylvania, and Muhammad recalls being harassed by white students as he and others gathered to march.

Photograph courtesy of the The Daily Pennsylvanian

A month later, Shaniqua McClendon was still thinking about that last day of class, and how Muhammad had warned them not to suppose that the hard, complicated work of reimagining whole systems and institutions was someone else’s responsibility. One such institution, McClendon says, is HKS, which has struggled to increase diversity in its ranks. As one of only two tenured African American professors, and only the third in HKS history, Muhammad has been a vocal advocate—especially after the recent departure of three black administrators—for hiring and retaining faculty and administrators of color. He is also a magnet for nonwhite students, says McClendon, who is president of the Black Student Union. “He’s been very generous with his time,” she says. “When you’re faculty or staff of any marginalized community, the students who identify with you flock to you.” Tanisha Ford and Carl Suddler, two former graduate students at Indiana, where Muhammad taught and lived from 2005 to 2011, tell a similar story, about how he and his wife, Stephanie Lawson-Muhammad—and their three children, Gibran, Jordan, and Justice—took time outside the classroom to make the very white Midwestern town of Bloomington feel less foreign to black students who were often far from home.

“Correct Your Mistake”

In biographical notes about Muhammad, two facts always come up: that he is a native of Chicago’s South Side, and that he is a great-grandson of Elijah Muhammad. The Nation of Islam leader died when Muhammad was two years old, and his parents divorced not long afterward, so he wasn’t raised as a Muslim, as his father had been. Instead, his experience of his great-grandfather came mostly through extended family—aunts, uncles, cousins, his grandmother. And through his father, Ozier Muhammad, who worked as a photojournalist for Ebony, Jet, Newsday (where he won a Pulitzer Prize), and The New York Times and sometimes took his son on assignments. “He had grown up with this very rich nationalist tradition of celebrating black people,” Muhammad says, “and I got a lot of that from him, and a lot of curiosity about African-American history.”

Muhammad’s mother, Kimberly Muhammad, was a teacher, and then an administrator, in the Chicago public schools, where her specialty, she says, was “unusual projects.” One year it was bringing order to a homeless shelter for families that had been overrun with prostitution and drugs; another year, raising attendance in violent neighborhoods with a program that recruited parents to walk their children to school—it worked because the gang members shooting at each other were also children of those same parents. In the mid 1970s, she and Muhammad came close to integrating a white school. Among the first generation of black teachers sent into classrooms in the mostly white neighborhoods of the city’s North Side, she had obtained special permission to enroll her son in kindergarten at the school where she taught. It didn’t last long. “I showed up one day and all hell broke loose,” Muhammad says. His mother remembers the community delivering a three-word ultimatum to the school’s principal: “Correct your mistake.” Her son would be in seventh grade before he attended an integrated school.

And yet the neighborhoods where he grew up were, for the most part, less segregated than the rest of the city, a mix of working class and middle-income families, populated by African-American professionals—doctors, dentists, lawyers. The Nation of Islam has a large presence in the Chatham neighborhood, and Hyde Park, about 20 blocks north, is home to the University of Chicago. “Hyde Park was, then and now, a kind of relative racial utopia, as much as we can imagine racial utopias exist, which is complicated,” Muhammad says. “But it was not a big thing to be a black kid with white friends or vice versa” (although looking back on it, he remembered that when the police stopped him and his white friends out after curfew, it was always his ID they wanted to see). His closest friend was a white classmate named Ben Austen, now an author and magazine writer in Chicago, and through junior high and high school, the two worked together at a neighborhood computer store, where by age 15, Muhammad was the de facto assistant manager, closing out receipts, making bank deposits, doing payroll. When he left for college, he thought he was heading toward a career in business.

But Muhammad arrived at Penn during the 1980s culture wars, when universities across the country were implementing affirmative action programs against intense opposition, and early programs for racial diversity and inclusion were just launching. He remembers celebrating Martin Luther King Day for the first time ever his freshman year. “Everything was brand new,” he says.

African-American students, then about 5 percent of Penn’s student body, ate together in the cafeteria and hung out together in the quads. Some lived in a residence hall named for DuBois, who had done field studies for The Philadelphia Negro as a Penn sociology researcher in the late 1890s. Because African American students were vastly outnumbered in classrooms, “All these other social spaces became very robust cultural sites, for you to feel like you belonged,” Muhammad says, not only in the African-American community, but at the wider university. And he did feel like he belonged. “Until one day, I didn’t.”

A series of racially charged run-ins on campus made his last couple of years at college unexpectedly tumultuous. In the spring of his junior year, four Los Angeles police officers were acquitted in the beating of motorist Rodney King, and a spontaneous protest coalesced at Penn. As the demonstrators assembled outside the DuBois House to march to City Hall, white students opened their windows and dropped eggs and shouted “racial things,” Muhammad recalls. Another incident took place the following year, in 1993. A group of black sorority sisters—one of them Muhammad’s then-girlfriend—were holding an outdoor event when a student shouted at them from a nearby dorm window, “Shut up, you water buffalo!” The women, and Muhammad, took the term as a racial slur; the student, who was Jewish, later insisted it was harmless Hebrew slang. The sorority sisters filed a racial harassment complaint, and the ensuing clash made international news.

In Hyde Park, “Khalil moved easily with everyone,” Austen says. “And to suddenly be in a place where racism was overt—I think that really shocked him.” In his last semester in college, a conflict erupted between Muhammad and a conservative columnist for the student paper, The Daily Pennsylvanian, who wrote that affirmative action had lowered the university’s admission standards and denounced Martin Luther King, calling the holiday in his name “wrongheaded.” The columns outraged Muhammad. He lodged a formal complaint with Penn’s administration, and when that process began to drag, he and 200 others published a sharply worded letter to the editor. To further the protest, the Black Student Union planned to seize copies of the newspaper and replace them with placards explaining their grievance. In the aftermath of his resulting arrest, when the police lawyer lost control, something in Muhammad finally, fully shifted: “It just circled back to everything: the Rodney King march, the climate on campus, the police investigation, the whole thing.”

“Blacks Somehow Corrupted Justice?”

He started graduate school at Rutgers just as O.J. Simpson was about to go on trial for murder. That first year, he roomed with a Dutch student who was already deep into his philosophy dissertation, but spent long lunch breaks watching the trial on television. Muhammad sometimes watched with him. “I had no investment in O.J. Simpson,” he says. “He was just a guy jumping over chairs in Hertz commercials when I was a kid.” But the spectacle was interesting.

Then came the verdict, and the uproar. Amid the cries for criminal-justice reform and overhauling jury selection and the wildly divergent reactions among whites and blacks, Muhammad couldn’t help but think back to the Rodney King acquittal—“a motorist pulled over and damn near beat to death.” In class he was learning about the “absolute racial terror” that had unfolded a century earlier in the American South, where black people could not even testify in their own defense. “How do you square that with the idea that maybe one black man did get away with murder—and now the entire criminal-justice system needs to be reformed? Because blacks somehow corrupted justice?” Muhammad’s face flattens into a tight smile. “I mean, that really struck me.”

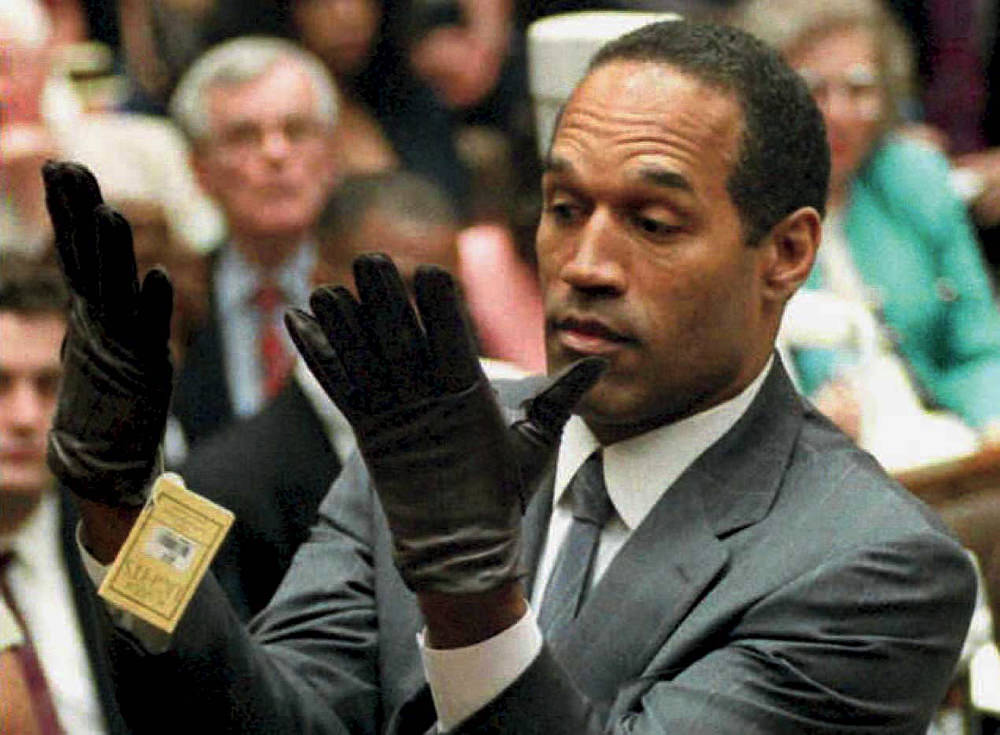

White Americans' reaction to the O.J. Simpson verdict became a turning point for Muhammad's research.

Photograph by Vince Bucci/AFP/Getty Images

But the history of the South didn’t fully explain what he was seeing televised from Los Angeles. It didn’t explain the Rodney King beating and the officers’ acquittal and the lack of outrage that verdict had generated among white Americans across the country. What was missing, he realized, was a chronicle of the North. He began to wonder: what happened to black people when they moved to places like Chicago, New York, Philadelphia, and even Los Angeles? What were their experiences in these relatively liberal cities where criminal justice was supposedly free of the racial bias that defined the South?

In the archives, he found a vast literature about the lives of European immigrants in big cities: “And the story was mostly the same: these people came here with expectations of a better life for themselves, of finding the streets paved with gold, but instead they found slums and ghettos and tenements, and they had to do all the paving themselves.” In these narratives, crime became a way of life, a way to survive and to make sense of their alienation, until they were incorporated into society and Americanized.

But the archives were mostly silent about black people in those same big cities, the migrants who had fled Jim Crow. “They too wanted jobs and to work and to have a better life for themselves,” Muhammad says. “They too were ghettoized and alienated. Why wouldn’t the same ideas apply?” As he began to write his dissertation, which led eventually to Condemnation, it became clear to Muhammad that “the stakes for understanding this early history were incredibly high, in order to change the discourse about black pathology and the prevailing thesis of cultural poverty and personal responsibility….That’s kind of what Rodney King and O.J. Simpson broke open: the possibility for seeing things differently.”

A few months after Condemnation came out, he received a call from the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, which was searching for a new director. A part of the New York Public Library system and a neighborhood fixture in Harlem, the center is a deep repository whose genealogy he recites with obvious pride: the place Du Bois and Paul Robeson turned to as a resource for their scholarship and artistry, where the painter Jacob Lawrence took history lessons as a teenager from Ella Baker, who became godmother to the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. As adolescents, Harry Belafonte, Ruby Dee, Ossie Davis, and Sidney Poitier took acting lessons together in the basement—then called the American Negro Theatre, that stage launched their careers. “Langston Hughes walked through the Schomburg’s doors in the 1920s and didn’t leave for four decades,” Muhammad says. In the early 1990s, Hughes’s ashes returned, to be buried in the main floor.

At Indiana, Muhammad had come to believe there was a wide gap between public debate and the work of scholars in American and African American history. “The Schomburg was built to close that gap.” As director, he raised the center’s attendance and launched renovations. He added more educational programs for adults and convened public talks that compelled academics to translate their work to general audiences. “I wanted to build on the black public sphere that is embedded in the DNA of that institution, and to build on it in ways that would scale up to every kind of American, every kind of immigrant, every kind of person who could learn about these stories that have been systematically erased or denied or silenced,” he explains. “We learn a lot about a country by how you treat ‘the least of these.’ And the story of black people in this country is in many ways the story of the expansion of the possibility of democracy. I mean, you don’t get birthright citizenship without the Fourteenth Amendment,” which granted citizenship to former slaves. The expansion of democracy is “undeniably, inextricably linked to the great turmoil of black life in the nineteenth century.”

“Statistical White Flight”

Muhammad’s current book project, tentatively titled “Erasure,” tells Condemnation’s mirror story: how white criminality became invisible in the popular imagination. At a talk last fall at Boston College, he posed a challenge to his audience. “How many Italian Americans committed armed robbery last quarter, or Irish Americans committed murders?” he asked. “I’ll give $100,000 to anyone who answers that question.” A burst of laughter rose, and quickly fell. “Why can’t you answer that?” he continued. “Because we stopped keeping track of what Italian-American or Irish-American criminals were doing a long time ago.” By the 1930s, arrest records no longer noted whether a white perpetrator was foreign-born, or his or her ethnicity. Muhammad calls this “statistical white flight.”

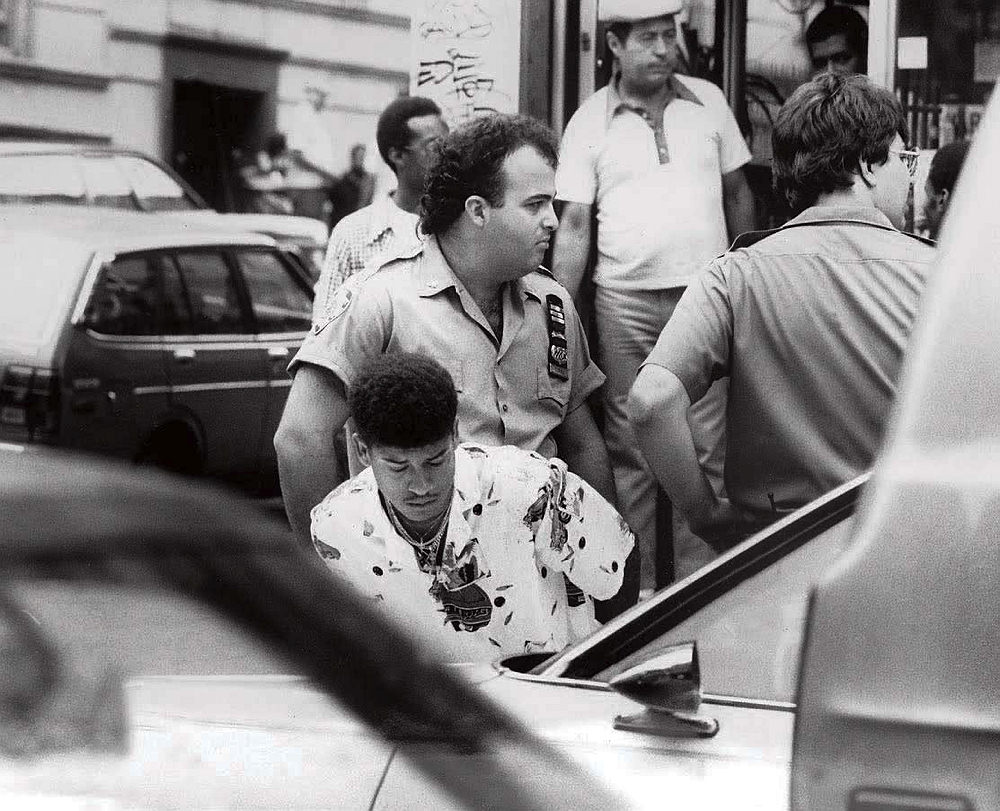

Police responses to the 1980s crack-cocaine epidemic, which affected mostly black communities, were punitive and unforgiving, Muhammad recalls.

Photograph by Willie Anderson/NY Daily News via Getty Image

He is still working out the arguments that will frame the book, but its narrative will build toward the current opioid crisis. He notes how differently politicians and police treat the mostly white Americans caught up in the epidemic of opioid addiction, as compared to the harshly punitive reaction during the 1980s crack-cocaine epidemic, which affected mostly African Americans. But Muhammad also reminded his audience that black heroin users were “public enemy number one” in Richard Nixon’s America—and pointed out that even though researchers had been studying white opioid use since World War I, Southern blacks at the time bore the primary stigma for an addiction that, even then, evidence showed was majority white.

Meanwhile, opioid addiction, which has devastated white communities, has sparked a softer and more understanding response from police.

Photograph by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

An important part of the story is the Baumes Laws, short-lived and shockingly brutal statutes from the 1920s. A precursor to current three-strikes laws, the Baumes statutes sent those with four felony convictions to prison for life, without the possibility of parole. Intended to catch big-time gangsters during Prohibition, the laws ended up ensnaring mostly petty criminals—almost all of them white. Within a few years, judges and prosecutors revolted; juries began refusing to convict. The former warden at Sing Sing Prison spoke out against the laws. Then-governor Franklin D. Roosevelt, A.B. 1904, LL.D. 1929, fought for and won their repeal on the eve of his presidential inauguration. “And so there was what I would call the first moment for the possibility of mass incarceration,” Muhammad says. “And the whole thing unravels, really quickly.”

The story he’s still investigating involves the middle decades of the twentieth century: “What happens in post-World War II America in these imagined utopias of white suburbs?” In cities and towns where the police blotter, like the population, is mostly white, he says, crime reporting doesn’t lead to moral panics and questions about broken culture. “If a critical mass of your white population is engaged in criminality, whether it is violence or nonviolence, drugs or non-drug-related, then the solution cannot be law enforcement as the blunt instrument of social control,” he says. “There’s a tipping point, where if this many white people are engaged in criminal activity, it can’t be them. It’s got to be something wrong in society. That’s what happened during Prohibition, and that’s what’s happening in the opioid crisis.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Last October, Muhammad sat down at HKS with Derek Black, a former white nationalist whose defection from the movement made news during the run-up to the 2016 presidential election. Black and Muhammad talked about the alt-right rally in Charlottesville, Black Lives Matter versus Blue Lives Matter, dog whistles, racial violence, failures in education, and the ideological conversion that began for Black in college. His father, Don Black, founded the website Stormfront, and at one point Derek Black warned the audience, “There’s nothing about white liberals that makes them immune to white supremacy”—an assertion that echoed Muhammad’s findings that both liberals and conservatives participated in casting blacks as criminals during the Progressive Era. Black marveled at how the white-nationalist talking points he once used to try to recruit newcomers had become mainstream political commentary. “And the main part of that,” he said, “is ‘Black people are more criminal.’”

The conversation seemed to affect Muhammad deeply—in the days and weeks that followed he kept bringing it up in other forums. After the event ended that evening, he shook Black’s hand and walked back to his office in the falling dark, full of thoughts. He recalled something Black had said about the difficulty and discomfort of anti-racism work, how it cannot be passive or partial. In class, Muhammad was teaching a parallel idea, about the inadequacy of merely tinkering with racially unequal systems, and how history both demonstrates the need for deeper, more arduous change and opens the space that makes that change possible.

On stage, Muhammad had shared a story about a trip in 2015 to Germany, where incarceration and crime are both low. He was part of a delegation of U.S. prison commissioners, governors, reformers, scholars, and a former inmate, whose purpose was to gather lessons to help reshape the American prison system. The trip was organized by the Vera Institute, a criminal-justice reform organization, where Muhammad completed a two-year fellowship immediately after graduate school (and on whose board he now serves), and the group toured several German prisons. Sentences there are dramatically shorter, wardens are often trained psychologists, and the focus of imprisonment is on rehabilitation and re-socialization. Inmates often cook their own meals and wear their own clothes; furloughs allow them to spend time with family before they’re released. “It’s more professional in every way,” Muhammad told the HKS audience, especially “in shielding from the politics of vengeance, which very much animate the United States.” And the rights of Germany’s incarcerated are guaranteed by a constitution that the United States helped write.

After the flight home, Muhammad was flagged in customs and sent for additional screening, unlike his colleagues, almost all of whom were white. When the customs agent asked why he’d been in Germany, Muhammad said he was there to study how and why the German prison system does a better job than the American at looking after its incarcerated population.

“I can tell you why,” the customs agent said. “They don’t have as many black people.”