A map is not merely an image of the earth, precisely plotted and filed as a scientific record. It also reflects political relationships among peoples and states, and choices about how to represent the world in two dimensions. Maps from the eighteenth century aided those profiting from the Atlantic slave trade; twentieth-century wartime maps plotted U.S. battle strategy against Japan.

Some of these maps, and about half a million others, are held by the Harvard Map Collection, which marks its two-hundredth anniversary this year. Its current Pusey Library exhibition, “Follow the Map: The Harvard Map Collection at 200,” combines selections from its holdings with the history of its donors, scholars, and curators. Their stories also trace the modern history of the world, and different ideas about how to visualize it. The exhibit begins in 1818, when Harvard acquired the library of Christoph Daniel Ebeling, a German who was a leading scholar on the geography of North America, despite never having set foot on the continent. The University had wanted to obtain the library and finally did with the help of Israel Thorndike, who purchased the maps for $6,285 and donated them. “Thorndike made his fortune in the Caribbean trading both commodities and enslaved Africans,” a text near the front of the exhibit notes. “Throughout its history, the map collection has always had the history of violence in its very structure.”

“I definitely felt more free to tell that historical story because of the Harvard and Slavery project,” says David Weimer, Ph.D. ’16, librarian for cartographic collections and learning and the lead curator of the exhibition, referring to the recent decisions of Harvard and other universities to acknowledge their ties to slavery. “If you’re going to tell the story of how the collection came to be, it’s incomplete if you don’t explain how someone got the money to do it. Slavery is how.” What ought it mean for the map collection to reckon with its ties to slavery? Part of the answer, Weimer continues, is to “help people think about how all of our lives are structured by the history of slavery, and where the economic system that we are now in comes from.”

A tourist map of Nikko, donated by Ernest Stillman, A.B. 1908

Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

Many motivations have existed to create maps: to navigate from one place to another, to understand what the earth looks like as a whole, to subvert some prevailing idea about what the world looks like, to memorialize certain places or tourist sites. “Anytime someone is trying to understand a phenomenon that has a spatial dimension,” Weimer says, “they’ll use maps.” By the end of the eighteenth century, maps were neither rare nor particularly expensive; most households in the United States had a map on the wall. One exquisitely detailed Japanese tourist map of Nikko, donated by Ernest Stillman, A.B. 1908, an avid traveler who gave his Japan collection to Harvard, depicts the city’s shrines and waterfalls and could easily serve as artwork in a private home.

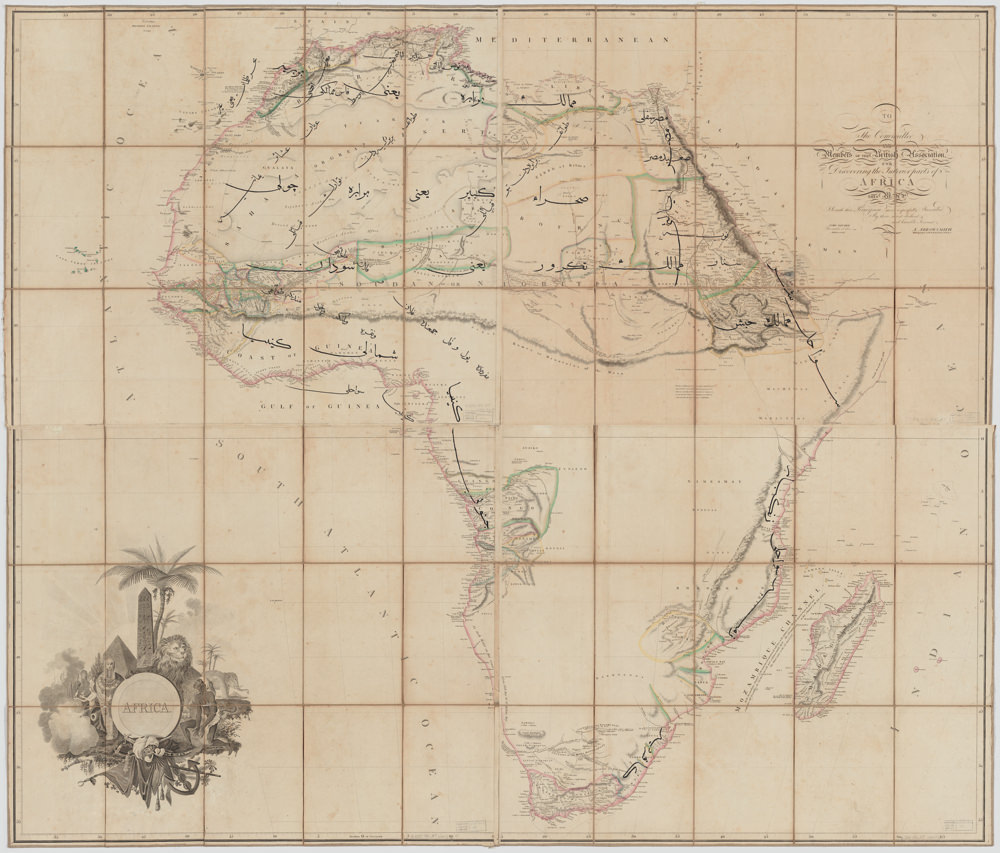

A surprising number of “Follow the Map” pieces double as objects of beauty in their own right. “There’s an intersection between what is beautiful and what is clearly legible and communicates straightforwardly,” Weimer says. A 1944 map from the U.S. Navy Intelligence Section, donated by a Harvard staff member who served in the Battle of Iwo Jima, details the beaches on the island the United States prepared to invade. Its beautiful details—the pale color palette and undisturbed island—are almost creepy against the backdrop of World War II. A visually captivating 1811 map of Africa by English cartographer Aaron Arrowsmith shows most of sub-Saharan Africa as completely empty, encouraging “European exploration—and exploitation,” a label notes. Arrowsmith’s place names have been overwritten by an unknown owner in a careful Arabic script.

Aaron Arrowsmith's "Africa"

Courtesy of the Harvard Map Collection

Maps can be applied to straightforward or tactical ends; they can also be fanciful, surprising, or plain weird. One example in the collection that is not part of the exhibit is an “upside-down” map created by the Wizard of New Zealand, a government-appointed public figure in that country; the map places New Zealand at the top and center. The Wizard “has developed a theory of the cosmos in which we’re not standing on the outside of the earth looking out, but that we’re on the outside looking in” at the universe, which is inside the earth, Weimer says. “Maps can be a playful or delightful way of thinking about what the world is and what our relationships are.” Separate from the exhibit, the collection also holds maps of imaginary places, like Narnia, Westeros, and the Nintendo game universe.

Creative visualizations can also have geopolitical or social interpretations; Weimer says his favorite maps have changed something about how he views the world. “Around World War II, you get a lot of people making polar projections as a political statement, which show the world with the North Pole in the middle to show how close the U.S., Russia, and Germany are, which is not at all clear from a Europe-centered rectangular map.” Other maps challenge the Mercator projection, the still widely used sixteenth-century mapmaking method that distorts the size of land the farther it is from the equator—making Europe and the United States, for example, appear larger than they really are relative to Africa.

In 1956, an exhibition text notes, the Map Collection was nearly dismantled after the then associate University Librarian judged that “the present generation of historians does not employ maps as intensively.” Many of its holdings were scattered across Harvard’s libraries, until a few decades later, when they were returned. Today as well, Weimer says, people often hold a misconception of maps as “narrow documents” that reflect the now-finished project of accurately mapping the world—or simply as a way of getting place-to-place—rather than as abstract representations that involve human choices. “Follow the Map” provides one corrective to this image of cartography. Initially conceived as a narrow exhibition about the original donation to the collection, Weimer and his colleagues decided instead to tell a broader story about mapping at Harvard, an undertaking that took them in “strange, interesting” directions—a map of migration patterns out of Ukraine; a brightly colored zoning map of Miami, representing the collection’s urban planning and design holdings. The Harvard Map Collection invites researchers from across the University to learn how to use mapping in their work; the objects on view this fall offer many unexpected ways in, to specialists and casual visitors as well.

“Follow the Map” will be open to the public at the Harvard Map Collection through October 27. On October 25 and 26, the collection will hold a symposium on the past and future of cartography.