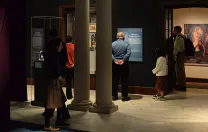

From the outside and the outset, the Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection is an oddity. The building, nestled in a leafy corner of Georgetown, in Washington, D.C., runs the architectural gamut, from its Renaissance-style “Music Room,” swollen with Italian marble and hung with tapestries, to the curved glass walls of the Philip Johnson Pavilion (both add-ons to the original Federal structure). Then there are the grounds: a series of terraced gardens where English meets Italian style, with (among other features) a swimming pool, a garden where Mexican pebbles are arranged in the shape of a sheaf of wheat, a brick amphitheater, and an orangery. Most of all, Dumbarton Oaks is thematically jumbled, specializing in Byzantine art, pre-Columbian art, and garden and landscape studies. As institutions go, it’s neither fish nor fowl: not quite art gallery, not quite anthropology museum. It’s a Harvard academic hub that is, and feels, far from Cambridge.

Jan Ziolkowski

Photograph by T.J. Kirkpatrick

“It’s donor-driven American philanthropy that accounts for the weirdness,” explains Dumbarton Oaks director Jan Ziolkowski. Those donors, Robert Woods Bliss, A.B. 1900, and Mildred Barnes Bliss, were a well-to-do Washington couple. With piles of inherited wealth but no children, they poured themselves into their home and its contents: “Their baby was very much Dumbarton Oaks.”

But within a few years of taking residence, in 1933, the Blisses were drawing up plans to give the property to Harvard. Their decision to found the museum during their lifetimes, and not after, made them more aggressively acquisitive. They expanded their collection of artifacts and bought books for an accompanying scholarly library (including texts on garden history, to complement the landscape then being designed by Beatrix Farrand). The Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection was inaugurated in 1940.

In this context, the museum’s next big exhibit, “Juggling the Middle Ages” (October 16 through February 28, 2019) is doubly odd, since it celebrates European medievalism. “It’s a little bit off-center,” Ziolkowski allows. He is also Porter professor of medieval Latin, and the show springs from his research interests, which lie catty-corner to Dumbarton Oaks’s triad.

“It’s important to me that people know that I’m not undoing our devotion to those areas,” he says. (The Blisses themselves felt that pressure: when they had their eye on a reliquary from the abbey of Melk, their art adviser scolded them in a letter: “I’m apalled [sic]…you’ll be in grave danger of scattering.”) “But,” Ziolkowski continues, “devotion to arcane fields means we have to redouble our efforts to explain to people why it matters.”

“Juggling the Middle Ages” traces the evolution of a once-popular story that fell into obscurity. It tells of a professional jongleur who decides to enter a monastery as a lay brother. There, he devises his own form of prayer. He strips down to his underclothes and does acrobatics in front of a statue of the Madonna until, exhausted, he collapses. His fellow monks call it blasphemy; the abbot investigates. Then the Virgin herself comes to life to comfort the tumbler. Overcome by the swift change from anxiety to relief, he expires, and Mary’s angels accompany his soul to heaven.

Ziolkowski first encountered the story while working on an essay about nonverbal rhetoric. He’d been investigating literary references to monks using sign language to communicate on days when they’d vowed to be silent.

“I looked at the whole piece and I found it just electrifying,” he says, “because it showed a man who was a worldly performer, who left the world and entered a monastery because he felt dissatisfied with the frenetic pace of life.” But, Ziolkowski continues, once the entertainer got inside the monastery, he found himself differently depressed. He felt inadequate, thinking he had nothing to offer amid a brotherhood of people who could sing and read and speak Latin. Yet, eventually, he found his own way to communicate his love of God.

The tale and its afterlife became a modest obsession. As he researched its different permutations, and his study got longer and longer, he realized, “This is becoming bizarre.” Still—despite how “People around me have thought that I needed an intervention”—he pushed on. For Ziolkowski, the story’s quirks were an occasion to meditate on deep, fundamental themes. “It looked as if it would promote monastic life and yet the holiest person in it was not a monk,” he says. “It brought up a lot of issues of, what is prayer? What kind of gift can we give to the divine or to each other? What’s the role of art in society? What’s the role of art within the humanities? These questions grabbed me.”

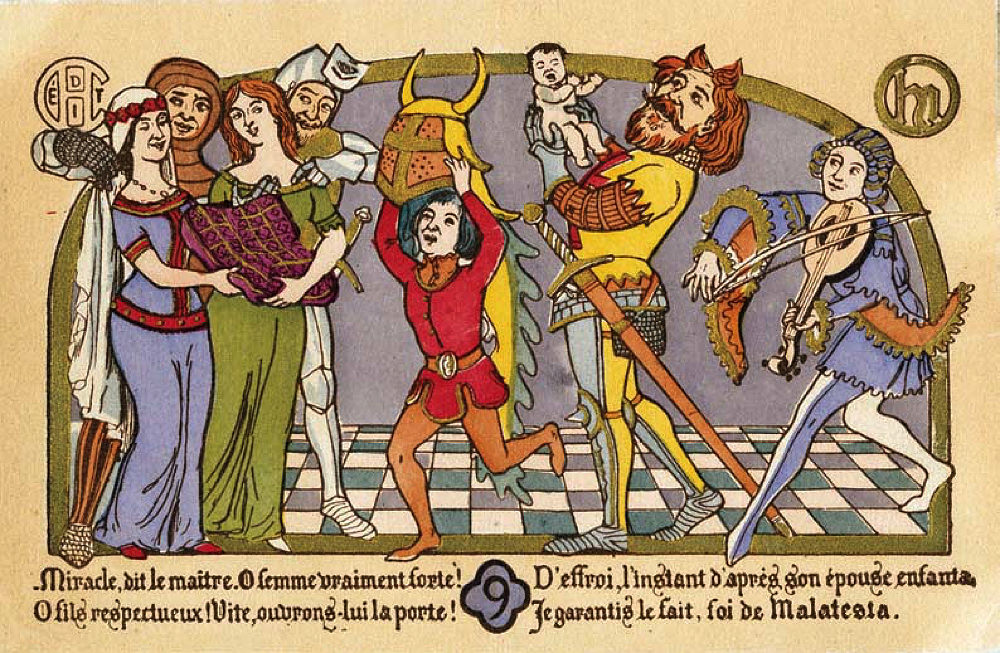

(Click on arrow at right to see a gallery of images.) A card by French artist Henri Malteste (1890s)

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

A card by French artist Henri Malteste (1890s)

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

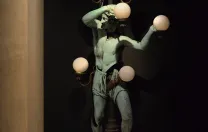

An acrobat, in limestone (c. 1150-1170)

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

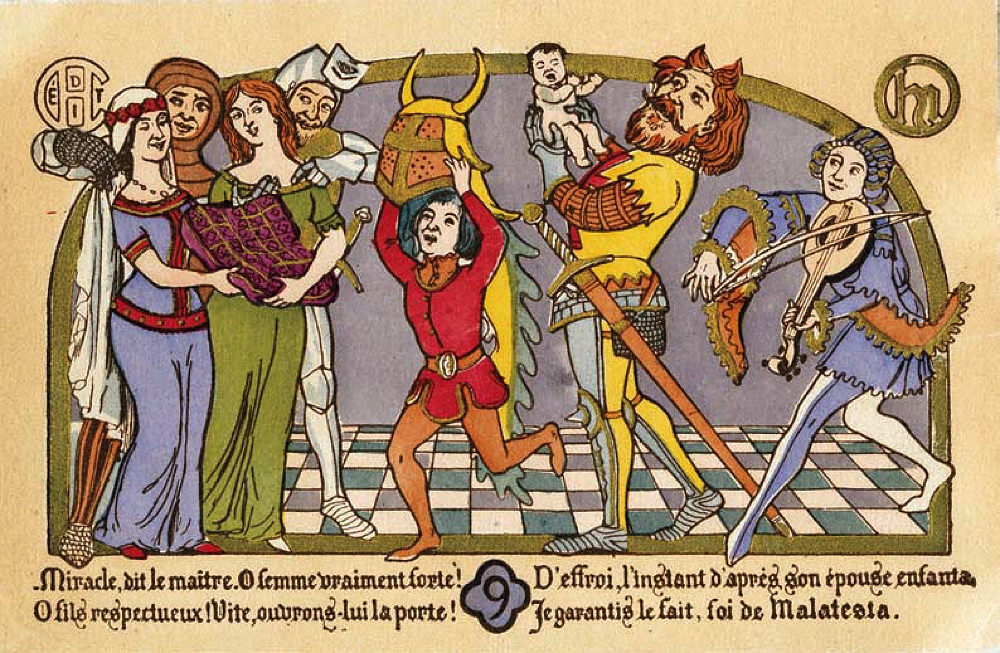

R. O. Blechman images for his version of the tale (1953 and later)

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

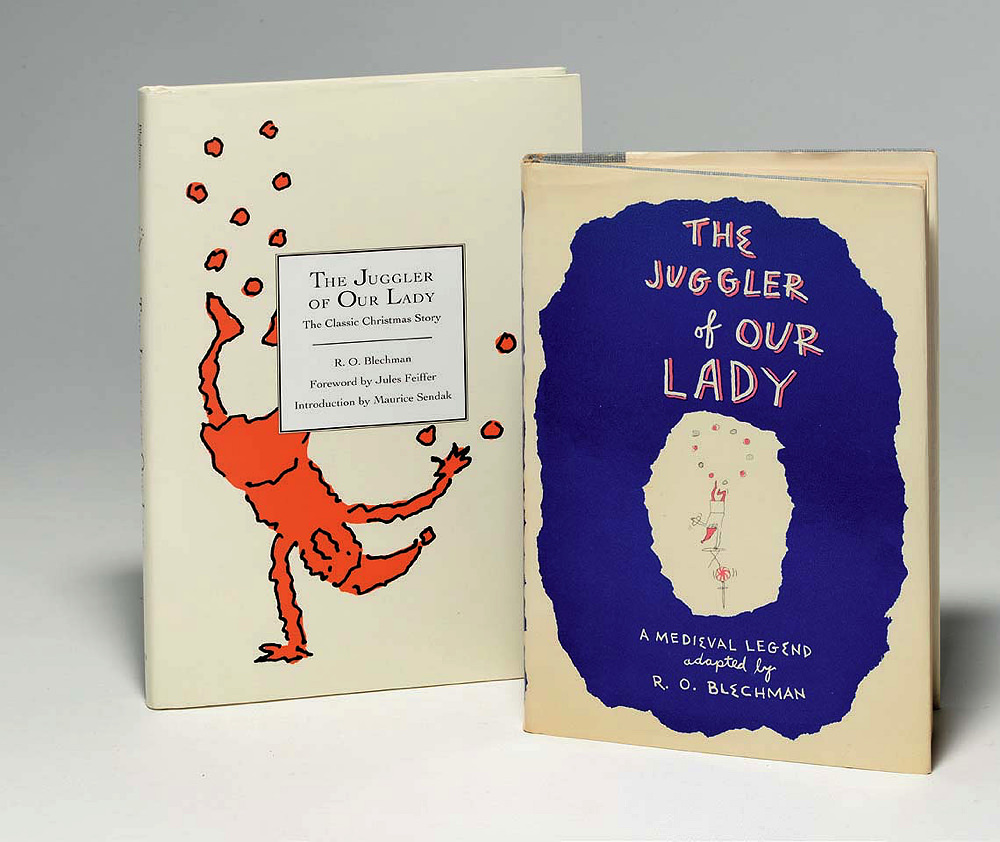

R. O. Blechman images for his version of the tale (1953 and later)

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

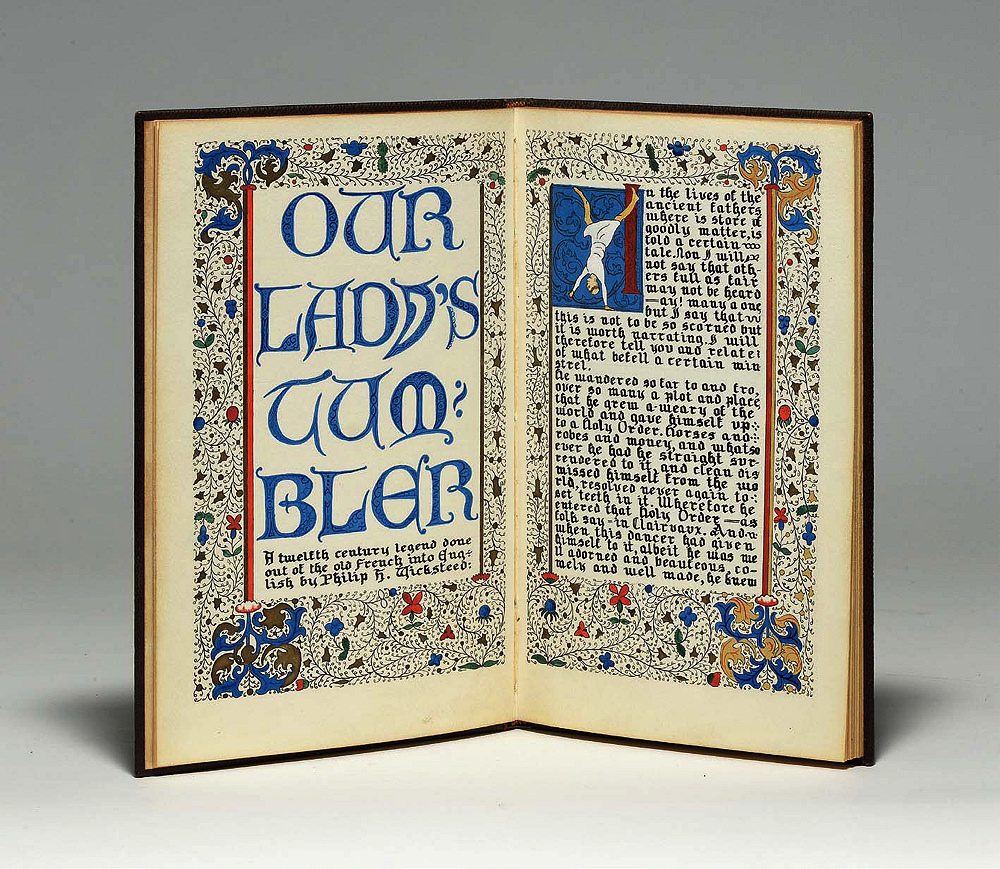

An early twentieth-century calligraphic retelling,…

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

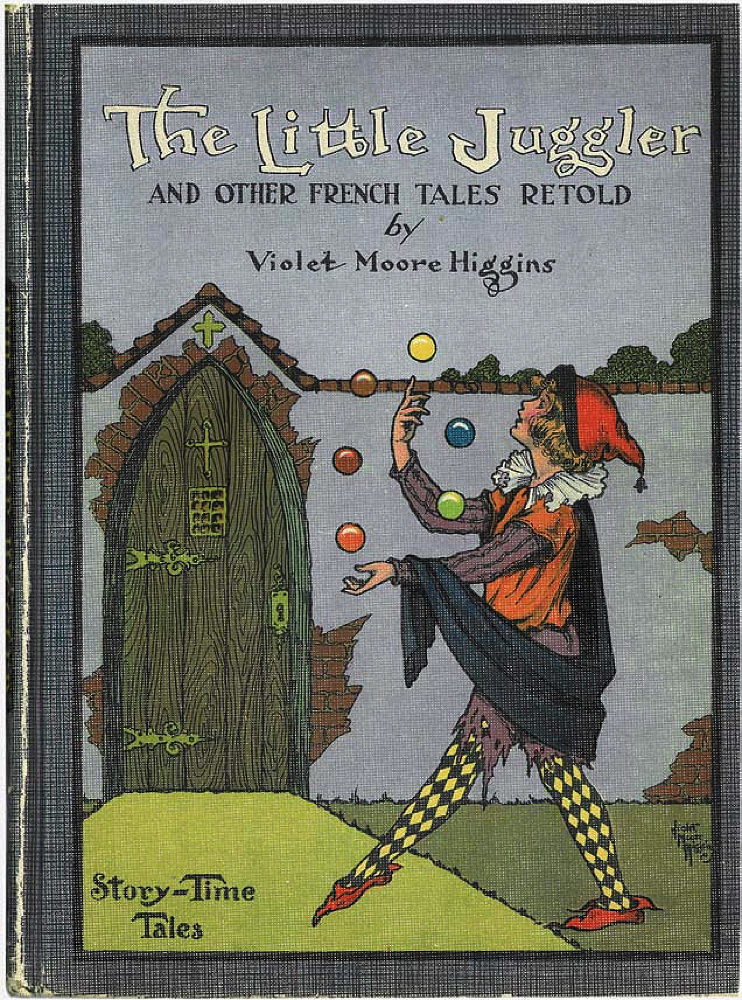

…a 1917 version,…

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

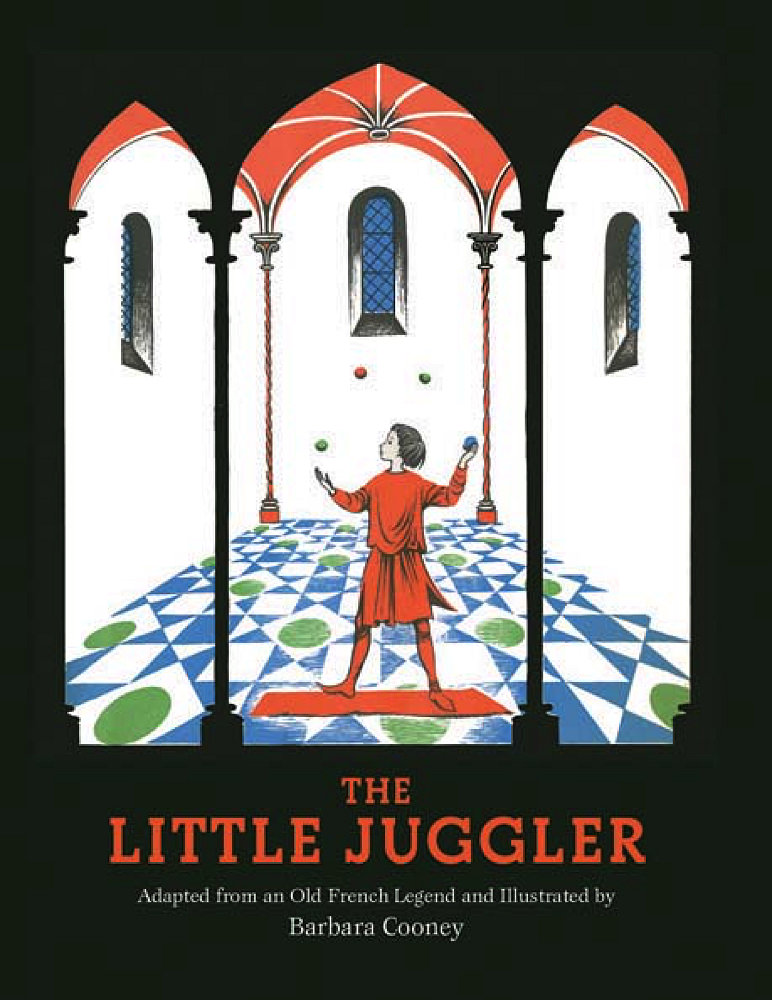

…and a 1961 retelling

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

That on-and-off side project, unfolding over more than a decade, has now resulted in The Juggler of Notre Dame and the Medievalizing of Modernity, published this year by a leading open-access academic press. Its six volumes trace the story from its origins as a medieval French poem, “Our Lady’s Tumbler,” told in 342 rhyming couplets, and its rediscovery in nineteenth-century Paris, feverish with renewed interest in all things Gothic: from Victor Hugo’s Hunchback of Notre Dame to the restoration of churches, monasteries, and monuments destroyed during the Revolution. The book then follows the tale’s translation into English, and its transmission in Britain and the United States, influencing Gothic revivalism in those countries. “Look, I’m at the point in my career where I’ve gotten way, way, way past the publish-or-perish part,” Ziolkowski says of his approach to the project. “I’m just going to do this the way that seems right to me.”

He also collected images to illustrate the work, starting with paper ephemera depicting the juggler and other Gothic motifs, and then moving on to larger and more unusual objects. Then, he says, “I realized that I’d accumulated this array of materials that has never been gathered together before, and will never be gathered together again, including some really beautiful things.” And he’d learned a lot by directing Dumbarton Oaks: “I’ve never curated anything, I’m not an art historian, I’m definitely not a museologist, but I thought, you know, let me go ahead and give it a go and try to put on the exhibit.”

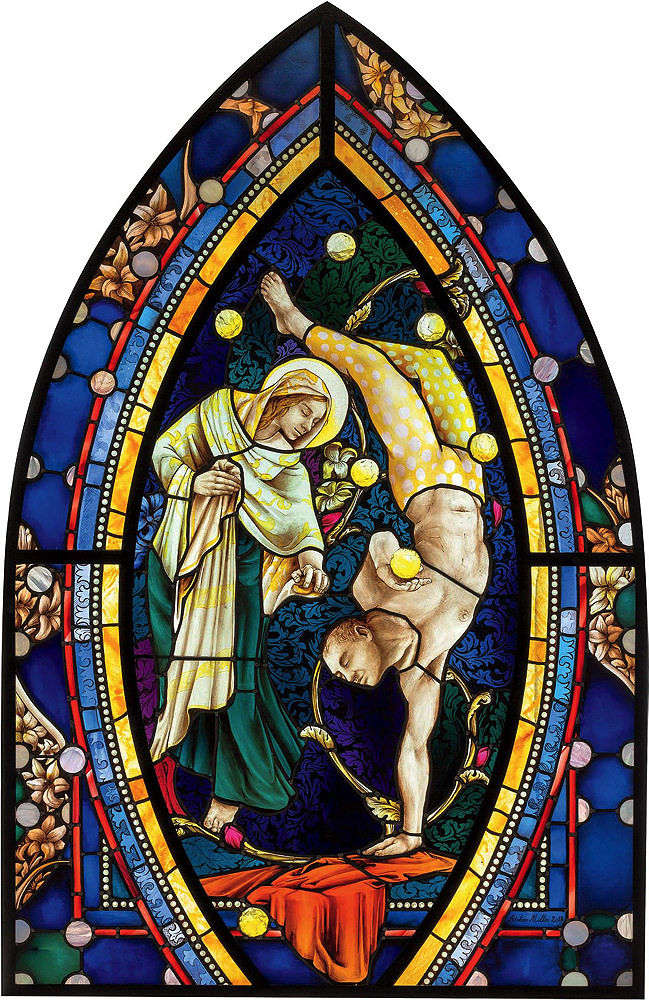

The exhibition starts in the front lobby, where the juggler will be presented in an all-new format: stained glass. (Ziolkowski commissioned this original artwork from a fabricator and restorer he knows in France.) Displays explain the tale’s underlying elements, in sections focused more closely on the juggler himself and on representations of the Madonna and her various apparitions. From there, “Juggling the Middle Ages” unwinds through the story’s retellings over time, including in a three-act opera by Jules Massenet and a plethora of children’s books in many languages. (The Dumbarton Oaks imprint at Harvard University Press is bringing several back into print: Barbara Cooney’s The Little Juggler, from 1961, and two different illustrated versions of Anatole France’s short story, “Le jongleur de Notre Dame,” from 1890, which Ziolkowski has newly translated. They’re also releasing a coloring book.) There are branchings out into related tales, like the story of the little drummer boy who attends the birth of Jesus. Other sections explore the “medieval revival” in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the era’s aesthetics were incorporated in architecture and design.

The stained-glass window Ziolkowski commissioned, a collaboration with Paris-based artist Sarah Navasse and master craftsman Jeremy Bourdois, from Atelier Miller

Image courtesy of Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection

The resulting show is sprawling, diffuse. Ziolkowski’s search for medievalesque curios led him down at least several rabbit holes, and into other communities of aficionados. When he found a couple of antique radios shaped like cathedrals and tried to get them refurbished, he met the radio nerds. When he bought a handmade, bilingual edition of “The Juggler of Notre Dame” by Maryline Poole Adams—bound in green leather, and two inches tall—he found the miniature-book buffs.

Maybe it’s a kind of blasphemy to display a pilaster of an acrobat—a genuine medieval artifact on loan from the Metropolitan Museum of Art—next door to a “Holy Toast!” Miracle Bread Stamp that burns the Virgin Mary’s aspect into your breakfast. But this catholic sensibility is also of a piece with Ziolkowski’s general determination to make Dumbarton Oaks fun, not fusty. “We’ve been building slowly but surely in increasing different types of outreach,” he says, citing recent efforts in educational programming.

So the galleries will also include a pop-up theater area where visitors can watch R. O. Blechman’s nine-minute animated short about the juggler (based on his children’s book), and an excerpt from a 1950s television program. One retrofitted radio will broadcast a 1952 radio play, The Juggler of Our Lady. Dumbarton Oaks will partner with the District of Columbia Public Library to bring the beloved children’s-book author Tomie dePaola in for a reading of his book, originally published in 1978, The Clown of God. Ziolkowski will lend benches carved to resemble Gothic churches, fitted with new cushions so that parents can sit and read to their children. There will even be a painted wooden display where kids can pose for a photo looking like a juggler.

The gravitational center of this eclectic assortment is, essentially, Ziolkowski’s superabundant enthusiasm. He’s eager to show the public a broader view of the Middle Ages—what he calls its “transcendent and positive side.” These days, colleagues in his field are grappling with the ways in which white supremacists have co-opted various elements of medievalism, while in the culture at large, he says, “What we get, mainly, are negatives. We get Game of Thrones, we know about plagues and crusades and witch hunts, and many things that are depicted very darkly, but there’s this brighter side.” He wants to put people, kids especially, in contact with an enchanted past, and with the ideals of beauty and nobility that inspired him as a boy growing up in Princeton, New Jersey, reading C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien.

But he has other aims, too. “Look, honestly, what I would love would be to have a lot of people come to the exhibit, see different versions, compare them, talk with each other about them, and just…,” he pauses, “compare notes on something not depressing, not political, and to engage in healthy interpretation about something connected with the human condition. Because I think we need that.”

In a museum-rich city, Dumbarton Oaks is relatively removed from the fray—“isolated,” as Ziolkowski puts it, in its genteel, red-brick residential area of northern Georgetown. Last spring, he and his staff were finalizing plans with exhibition designers. Outside, the shorn grounds were recovering from winter maintenance, and the first cherry blossoms starting to bud. Overhead, helicopters juddered, going in and out of the Naval Observatory (“Mike Pence’s choppers,” someone joked). Suddenly the Blisses’ vision became easily apparent. “They wanted to pass down this way of life that they loved,” Ziolkowski explains. “They wanted scholars to have an Edenic, paradisiacal, serene setting for thinking.” For his part, he likes to think of Dumbarton Oaks as somewhere people can put aside “their obsessions with a divisive now” and contemplate the past.

Dumbarton Oaks does have a medieval aspect, with its scholars-in-residence poring over its treasures, gathering in the dining hall (actually called the Refectory) for lunch, taking a stroll in its walled gardens. Visitors may not find being immersed in the juggler’s tale all that strange. It’s a story, after all, about unorthodox devotion, and eccentric passions finding sanctuary.

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,