Drawing from the Harvard Art Museums’ extensive collection of Japanese woodblock prints, “Japan on Paper,” opening May 25, examines the versatile art form and its history. The technique was used “as early as the eighth century to produce Buddhist texts,” according to museum exhibit notes; the nearly 50 featured prints span the early Edo period (1615-1868) through the twentieth century, and capture cultural touchpoints—iconic mountainous scenery, Kabuki actors, and beautiful women—as well as contemplative modern portraits.

The innovative artist Suzuki Harunobu, of the Edo era, was especially known for his renderings of feminine grace. He pioneered the use of full-color reproduction technology that emerged in the 1760s, as evidenced in his Woman Running to Escape a Sudden Shower, c. 1765-70. Black slashes of rain charge across the paper, juxtaposed against billowing folds of her silky red-trimmed kimono, the open skirting revealing a lovely naked leg. The effect gives a subtle (or not so subtle) eroticism that feels surprisingly liberating—and modern.

To illustrate aspects of the printing process during the New Prints (Shin hanga) movement, almost 200 years later, the museum has mounted a series of images by landscape artist Kawase Hasui that were produced between 1945 and 1951. They all depict the same scene, of simple wooden houses by the ocean, entitled A Cloudy Day in Mizuki, Ibaraki Prefecture. Yet the mood of the place and forms differ depending on the shifting colorations, from sketched and water-colored versions to the rich blue tones of the fully realized woodblock color-print.

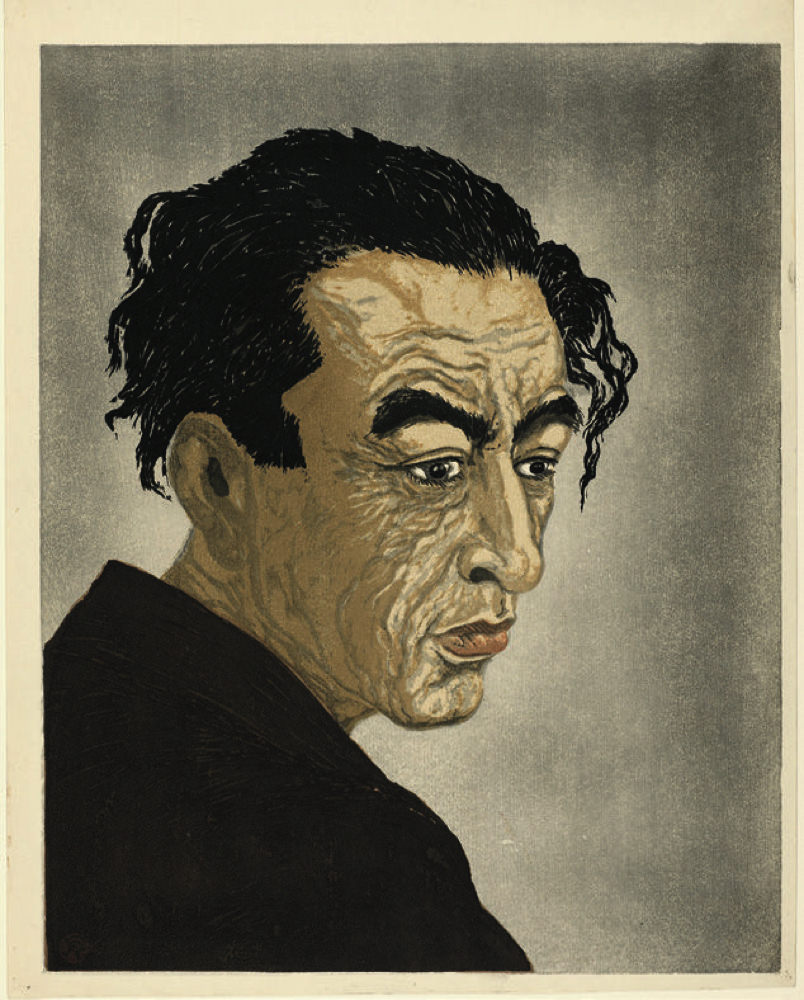

Perhaps the most haunting piece in the show is the Portrait of Poet Hagiwara Sakutarō (posthumous edition dated 1957; original dated 1943), by his friend the artist Onchi Kōshirō. It was created a year after the poet, hit hard psychically by the war and prone to depression and alcoholism, had died. Untamed black hair and deep furrows don’t hide eyes that, even cast downward, convey a soulful eloquence that’s hard to look away from.