In 2005, during her first year of graduate school, Elizabeth Hinton traveled from New York to California to visit her cousin in prison. In some ways, she understood what to expect: for most of her childhood, she’d known family members who cycled in and out of jail, caught up in drugs and addiction and poverty. Their experience was a large part of why, as a little girl, she had wanted to become a criminal defense attorney, and later, why she was drawn to African-American history and explorations of crime and punishment. That path would lead eventually to a career in a field that was just beginning to coalesce: the study of mass incarceration.

Even if prison was a familiar concept, though, witnessing it firsthand was shattering in ways she hadn’t anticipated. Her cousin was at the High Desert State Prison in Susanville, and to get there, she and her mother had flown to Reno, and then driven a rental car five hours to a motel in a town where everyone they saw knew why they were there.

Inside the gates, the two were screened, their clothing examined to make sure it conformed to the rules: nothing too tight-fitting, no jeans, no bras with metal. “Especially as a woman visiting a man in prison,” Hinton says, “you undergo a process of dehumanization and scrutiny—and criminalization—where you can be searched, where your body can be commented on, where you can be ridiculed by the guards, and where, if you don’t behave a certain way, you can be prevented from seeing your loved one.” She understood this humiliation to be an extension of the power dynamic and cruelty inherent in prison life. She knew that on the other side of the locked doors, her cousin was being strip-searched in preparation for the visit.

And then she stepped into the room where they would see him, a big space full of low tables and plastic chairs that reminded her of an elementary school. There were dull pencils for playing games like Scrabble (pens were forbidden), and vending machines along the wall, where people would line up to buy frozen foods—sandwiches, chicken wings, pizzas, pies—that tasted better than the prison meals they were used to. Most of the incarcerated were African American or Latino, and nearly all the guards were white. “And I looked around and saw all these black and brown families,” Hinton says: men talking to their children, sitting with their wives, with whom they could interact only in this room, whom they could touch only twice—hello and goodbye—and then only briefly. She thought about what all this meant for generations of children.

“It was really stark,” she says. “And I just thought, ‘Oh my God, how did this happen?’”

Origins of the Carceral State

A little more than a decade later, Hinton had an answer. In 2016, she published From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime: The Making of Mass Incarceration in America, a book that cemented her reputation, at the age of 33, as a rising star in a burgeoning field. In it, Hinton, Loeb associate professor of history and of African and African American studies, tells the story of how federal policies—shaped by presidential administrations and endorsed by Congress—ratcheted up surveillance and punishment in black urban neighborhoods from the 1960s through the 1980s, how criminalization was steadily expanded, and how all of this was driven by deeply held assumptions about the cultural and behavioral inferiority of black Americans.

Her biggest revelation—the central irony in a book full of them—is that the contemporary carceral state began to take hold, not under law-and-order conservatives like Ronald Reagan or Richard Nixon, the men usually held responsible, but under liberals, most notably Lyndon Johnson, whose Great Society social-welfare programs were enacted at the height of the civil-rights movement. Those programs began with sincere intentions but were never independent, Hinton argues, from federal policymakers’ “desire for social control, or from their concerns about crime.” In meticulous detail, she lays out how “the War on Poverty is best understood not as an effort to broadly uplift communities or as a moral crusade to transform society by combating inequality or want, but as a manifestation of fear about urban disorder and about the behavior of young people, particularly young African Americans.”

The notion that mass incarceration was a bipartisan project from the beginning—indeed, that its earliest innovators were social liberals concerned about poverty—was a significant finding. “And remember, when Elizabeth started this research, nobody was really working on the history of this crisis,” says Heather Ann Thompson, a historian at the University of Michigan (and a graduate and postgraduate advisor to Hinton), whose 2010 journal article “Why Mass Incarceration Matters” was one of the early publications that broke open the field. A flood of scholarship followed, but most of it, Thompson says, examined elements of present-day incarceration; “Elizabeth’s work shows how we got here. It helps us understand a part of the past we just didn’t understand before.”

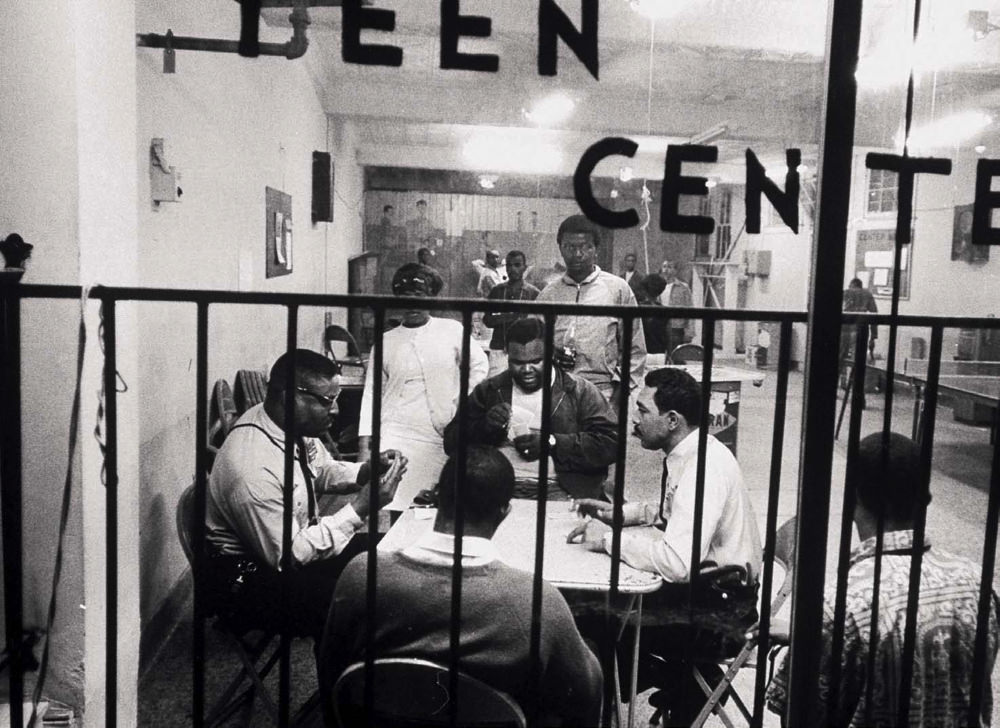

A police officer plays cards with locals at a Washington, D.C., teen center in 1968, part of a push to link policing and social services.

Photograph by Stan Wayman/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images

Hinton’s research led her through the White House Central Files of every administration from John F. Kennedy’s to Reagan’s, looking for any shred of information related to crime, punishment, and African Americans. Her requests to declassify documents turned up tens of thousands of pages of internal memoranda, reports, meeting notes, and correspondence (a few declassification requests are still pending with the Reagan Library). “Her work has definitely changed the narrative,” says Khalil Gibran Muhammad, professor of history, race, and public policy, whose 2010 book The Condemnation of Blackness documented the Progressive Era origins of the discourse linking crime and race (see “Writing Crime into Race,” July-August 2018, page 57). Tommie Shelby, Titcomb professor of African and African American studies and philosophy, was on the search committee that hired Hinton. “She’s a person whose work you have to engage with if you’re studying the penal dimensions of the state,” he says. “And not just in history—in political science, law, sociology; she cuts across fields.”

The story that unwinds in From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime is chilling. In March 1965, Hinton writes, President Johnson sent three bills to Congress that epitomized the federal government’s ambivalent response to the civil-rights movement: the Housing and Urban Development Act, the Voting Rights Act, and the Law Enforcement Assistance Act. The latter bill, signed into law a month after violent uprisings in Los Angeles’s segregated Watts neighborhood, marked the official start of the War on Crime. For the first time in U.S. history, the federal government began to take a direct role in local police, courts, and prisons.

Three years later, the Safe Streets Act created the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, which figures as a main culprit in her account. It funneled federal money into local police departments—a total of $10 billion by 1981 ($25 billion in today’s dollars)—to increase manpower, modernize forces, and arm officers with military-grade weapons. And it helped widen local law-enforcement patrols and surveillance operations in cities with large African-American populations.

Meanwhile, Johnson’s poverty initiatives increasingly gave way to crime-fighting, as programs dedicated to health, housing, education, recreation, and job training came to be partly—or sometimes wholly—administered by law-enforcement agencies. Even as federal policymakers recognized that joblessness, failing schools, inadequate housing, and inequality lay at the root of urban ills—including crime—they repeatedly turned to law enforcement as the solution.

These measures were backed by scholars at the time. Harvard political scientists James Q. Wilson and Edward Banfield advocated divesting from social-welfare initiatives, and sociologist Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s famous publication, The Negro Family (known as the Moynihan Report), popularized the idea of a self-perpetuating “tangle of pathology” among black families. All three, Hinton writes, came to view black poverty “as a fact of American life,” and black crime and violence as innate. Their ideas helped push the Nixon administration, several years later, toward a belief that black cultural pathology, not poverty, was the real cause of crime.

And so, in low-income black neighborhoods, law enforcement became a ubiquitous part of the social and political landscape, and strategies intended to identify residents at risk of becoming criminals encouraged authorities to provoke interactions with them, creating, Hinton notes, a feedback loop of crime and enforcement. A few saw the danger looming. She quotes James Vorenberg, a former dean of Harvard Law School and director of Johnson’s Crime Commission: “As soon as we start dealing with the kids in [certain] categories as potential delinquents, and we put that label on them,” he told a congressional committee in 1967, “we may be creating a self-fulfilling prophecy.” Yet Vorenberg, too, supported a strategy of surveillance.

The Nixon administration ushered in dramatically more punitive policies, withdrawing further from social reforms and rehabilitative measures in favor of harsher punishments: longer sentences, preventive detention, broad wiretapping, no-knock raids. Sting operations often created crime, setting up decoy fencing operations and whole underground economies that incentivized the poor and unemployed to steal from one another.

Using flawed predictions of African-American population growth, the administration set in motion a long-range plan to vastly expand and modernize prisons—“one of the first declarations,” Hinton says, of policymakers’ decision “to try to manage inequality rather than to ameliorate it.” Meanwhile, block grants pushed states to spend money widening their own corrections programs. When Nixon took office in 1969, the country had fewer than 20 federal prisons; by 1977, the government had opened 15 more—4,871 new beds, which came to be filled, Hinton writes, by the 4,904 new black and Latino inmates taken in during those same years.

Her narrative carries through the administrations of Gerald Ford, under whom juvenile-detention facilities multiplied and white youths were treated as merely troubled while black youths were dealt with as criminal; and of Jimmy Carter, who, despite his progressive intentions channeled millions of federal dollars to public-housing authorities for surveillance and patrols that failed to improve safety but made housing projects into pipelines to prison.

The book ends in the 1980s, with Ronald Reagan, the War on Drugs, and the prison population mushrooming as new laws put drug users behind bars, especially African Americans: policies hardened penalties for crack cocaine, associated with black drug users, far beyond those for powder cocaine, more commonly associated with whites. The Reagan administration tightened the connections between the military and police and initiated, under the Comprehensive Crime Control Act of 1984, the asset-forfeiture system allowing police to seize cash and property from accused drug dealers, incentivizing increased arrest rates and what amounted to theft among corrupt officers.

Yet for all the law-enforcement initiatives targeting urban black neighborhoods, those places remain plagued by crime and violence, Hinton observes, over-policed and under-protected: “The War on Crime and the War on Drugs are two of the largest policy failures in the history of the United States.” In the century between the end of the Civil War and the start of Johnson’s War on Crime, “a total of 184,901 Americans entered state and federal prisons,” she writes. Between 1965 and the launch of the War on Drugs less than 20 years later, state and federal prisons added another 251,107 inmates.

Today, roughly two million people are incarcerated in this country, 60 percent of them African American or Latino. The United States, with 5 percent of the global population but 25 percent of its prisoners, is home to the largest prison system in the history of the world, with an incarceration rate that is five to 10 times that of peer nations. Altogether, the federal, state, and local penal systems cost taxpayers $80 billion per year, and some states, Hinton writes, spend more money imprisoning young people than educating them.

The human cost is incalculably more: generations of young people of color, systematically removed from their communities, now living, she says, in “faraway cages.”

The Sociology of Saginaw

Hinton spent her childhood in the shadow of those crime policies. She grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan, the daughter of Ann Pearlman, a psychotherapist and writer, and Alfred Hinton, a professional-football-player-turned-art-professor at the University of Michigan. But deeper roots lay about an hour north, in Saginaw, a once-thriving industrial city to which her father’s parents had migrated from Columbus, Georgia, in the 1950s, joining thousands of other African Americans who came to the city during the war years and afterward to work in its factories and foundries.

“It’s a very typical American story,” Hinton says: General Motors offered her grandfather a job and a bus ticket, and he rode north in search of a better life for his family. “And just like so many,” she says, “he bought a house”—a little bungalow on a pretty residential street—“and integrated a white neighborhood.” Within five years, all the white residents had moved out, and in the decades that followed, manufacturing slowed and plants started closing. By the time Hinton was young, visiting from Ann Arbor on weekends, the vibrant autoworker neighborhood her grandparents had moved into was beginning to fall apart. The home next door became a crack house; others stood abandoned. Eventually, her grandfather (“Big Papa,” she calls him—her book is dedicated to him) left the neighborhood, too.

Amid the joblessness and hopelessness and worsening crime, some of Hinton’s cousins began to get into trouble. They were using drugs. They were in and out of prison, in and out of recovery and relapse. “And I understood why,” she says. “I mean, Big Papa bought this house and had so many hopes and dreams. And was soon living next to a crack house. The environment itself told the story.” To her, that story felt like a continuation of another one, which her family had been telling for as long as she could remember: about slavery and sharecropping and Jim Crow, about segregation and the civil-rights movement and centuries of racial oppression. The way she saw it, her cousins’ addiction and incarceration were inseparable from the poverty all around them in Saginaw: “I knew they were human, and I knew that like anybody else, they were complicated and contradictory, and that they were dealing with a particularly devastating set of circumstances.…It was something that weighed heavily over my childhood.”

Harlem residents confront police in 1970; the drastic rise of police presence in black neighborhoods often led to friction.

Photograph by Jack Garofalo/Paris Match via Getty Images

The sharp contrast to her own life and prospects in Ann Arbor, a college town with resources and a robust social fabric, corroborated her sense that what was happening to her family in Saginaw was deeply sociological, deeply tied to history. “I remember getting into arguments with friends in Ann Arbor about things like welfare and violence and incarceration,” Hinton says. “Because most of them didn’t have the same exposure—they didn’t have people in their families or in their lives who were on welfare, or in prison, or addicted to drugs. And so they didn’t have the same perspective.” Those debates, too, fueled a desire to figure out the factors she perceived to be at work, to map the contourrs more precisely.

Her first chance to do original research came in high school. She took an American studies class her junior year and wrote a paper, based on her reading of slave narratives collected in the 1930s, arguing that the Declaration of Independence legitimized slave revolts—“basically,” she says, “that, under its principles, they had a right to rebel.” A second research paper looked at FBI actions against the Black Panther Party, drawing on party co-founder Huey P. Newton’s 1980 doctoral dissertation, “War Against the Panthers: A Study of Repression in America” (her mother had a copy at home).

Hinton arrived at New York University’s Gallatin School in 2001 and carved out an individual major in historical sociology, exploring, from a black-studies perspective, the experiences of people of African descent in the Western Hemisphere. She worked as a research assistant for historian Robin D.G. Kelley, who was writing a biography of jazz musician Thelonious Monk, and fell in love with the archives. She began to see how research and storytelling could lift unseen narratives out of the slough of history.

Hinton wanted to chart a history of gang violence, to show how, for instance, drive-by shootings were not simply natural events, but distinct and particular, a behavior rooted in history.

She started graduate school at Columbia with questions in mind. “I really wanted to write about violence,” she says. “Because one of the big injustices I saw, and that frustrated me in those early debates with friends back in Ann Arbor, was that there was no historical explanation of violence in low-income communities of color.” It was still seen as something inevitable, a result of the “tangle of pathology” Moynihan had theorized about 40 years earlier. Hinton wanted to chart a history of gang violence in the late twentieth century, to show how, for instance, drive-by shootings were not simply natural events, but distinct and particular, a behavior that came from somewhere, rooted in a history of policies and disinvestments.

But the archives she needed didn’t yet exist, she soon discovered, in part because the data were difficult to obtain, stacked away in countless diffuse newspaper accounts and oral histories, and in official police records that often weren’t open to the public.

At about that same time, she began visiting her cousin in prison. And in that big room with the low tables and the vending machines and all those other black and brown families, everything shifted.

“How We Got Here”

On a late afternoon in mid March, Hinton is standing at the front of a first-floor Boylston Hall classroom packed to the walls with students and backpacks and the mild commotion of midterm anxiety. Her “Urban Inequality after Civil Rights” class is embarking on a discussion of policing and incarceration. “Every time rights are extended to African-American groups,” Hinton tells students, a diverse bunch of about 30 undergraduates and a few grad students, “there’s a subsequent turn toward criminalization and incarceration.” After Emancipation came discriminatory state laws known as “black codes,” then chain gangs and convict leasing. A hundred years later, amid the civil-rights movement, “We get another turn toward policing and confinement.”

Hinton’s lecture draws on some of the threads in her book—lingering on Nixon’s long-range plan for prison construction, Reagan’s militarization of the police during the War on Drugs, and the sting operations and mass arrests that came to characterize the War on Crime—but a couple of moments seem to hit the class especially hard. When Hinton explains that Nixon officials recognized early on the correlation between unemployment and incarceration rates, and took that link not as a motivation to create jobs, but as a justification for expanding prisons, an aghast silence fills the room. Hinton nods. “That’s something I can’t get my mind around,” she says. “That you can ignore the factors that fuel crime and incarceration and at the same time use those same figures as a basis for further incarceration.”

For many of the students, it is not the first course they have taken with Hinton. Since joining Harvard in 2014, she has amassed what one colleague calls “an enormous following.” Jackie Wang, a Ph.D. student in African and African American studies (and one of Hinton’s graduate advisees), served as a teaching assistant last fall for Hinton’s course “Mass Incarceration in Historical Perspective.” Enrollment was capped at 35, but Wang remembers that on the first day, more than 150 students showed up. The winnowing was difficult. “Students adore her,” Wang says (this past spring Hinton was awarded a Phi Beta Kappa prize for excellence in teaching). Brandon Terry, assistant professor in African and African American studies, calls Hinton “already bedrock” for the department, and for the study of inequality at Harvard. “She attracts as many graduate students as some of the senior faculty,” says Terry. “And her students are producing pathbreaking work on incarceration and the activism around incarceration.”

Hinton’s arrival (after three years at the University of Michigan—a postdoc followed by a faculty appointment) coincided with an inflection point in the national conversation on race and policing: about a month before her first semester in Cambridge, Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri. She remembers packing for her move amid the protests and watching in amazement as a new national consciousness coalesced around the issues at the heart of her work. She arrived to find the campus in upheaval. Sonya Karabel ’18 was a freshman that year and remembers Hinton’s fall course on the global history of prisons taking on a new urgency: “Suddenly we were learning this history not only to know it, but to grasp our own moment and to change it.” The following semester Hinton taught “African-American History from the Civil War to the Present,” and her classroom filled with students. Some of them had never taken a history course before, let alone African-American history. They told her they wanted to understand “how we got here.”

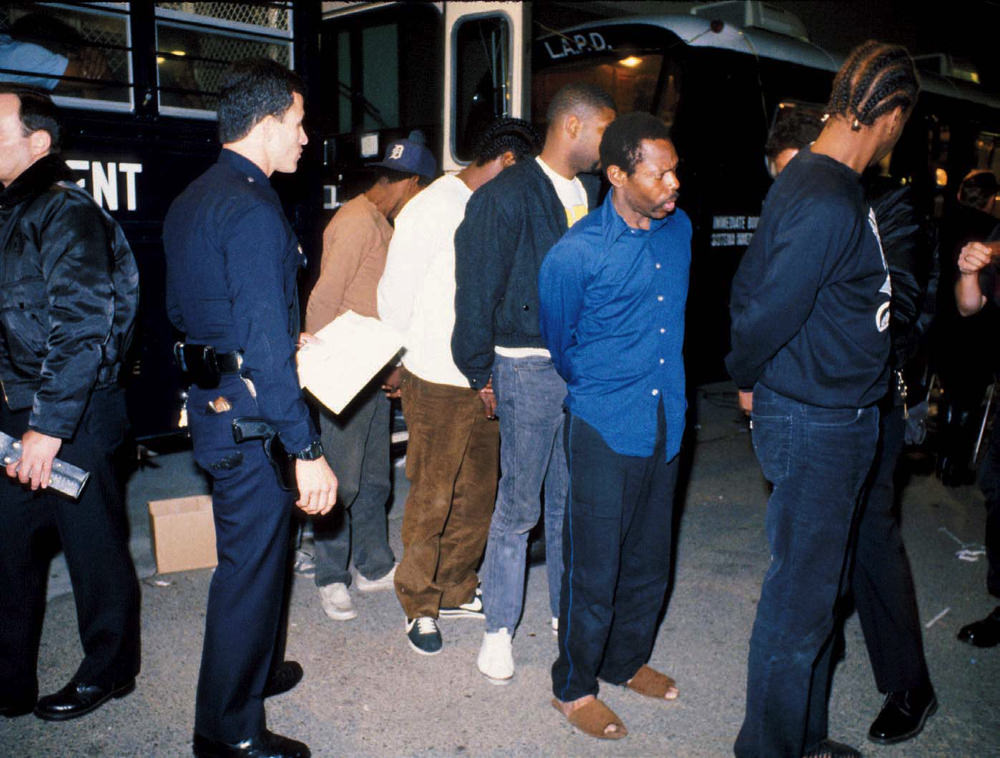

Los Angeles police with men in custody after a 1988 anti-gang sweep; officers arrested 1,400 residents in one two-day span that year.

Photograph by Jean Marc Giboux/Liaison/Getty Images

Outside the classroom, she was equally busy, helping students sort through the turmoil. “Elizabeth really rose to that challenge more than anybody else on the faculty,” says Terry. “She was doing multiple events a week”—student-organized panel discussions about race and policing—“and having students routinely break down in tears in her office.” Hinton, he says, is someone students turn to “when their sense of what their society is capable of delivering on has fallen apart. She’s a real source of support in those dark moments. And that doesn’t go on a person’s CV.”

Hinton remembers those days too. “There were a couple of weeks there where it felt like Brandon and I were doing an event every night,” she says, “and we’d have a line out the door during office hours, and, you know, you can’t get out of there.” But it’s an important part of the job, she believes. “It’s hard for me to say no to students. I think for a lot of young faculty of color, this is a kind of invisible labor that we do.”

Scholars as Activists

Just as she has found that teaching doesn’t only mean instruction, working as a scholar in carceral studies doesn’t only mean research. “She is a committed activist,” Heather Ann Thompson says. “In this field, it’s a logical expression of one’s work—you want to help try to undo the trauma in your findings. And she’s also a first-rate scholar. She’s a model for how to strike that balance.” Hinton has advocated for changes to incarceration policy, and she is “incredibly important,” Terry says, “for the movement toward a real reckoning with our history of incarceration.”

At Harvard, the scholar-activism balance has sometimes been uneasy. In 2017, Hinton and other history department colleagues endorsed the graduate-school application of Michelle Jones, who became an accomplished historian while serving more than 20 years in prison for the murder of her four-year-old son. Countermanding that recommendation, though, the University rejected Jones’s application (she’s now a Ph.D. candidate at NYU), a decision that made national news and sparked controversy; Hinton, who had championed Jones vigorously, was devastated.

More recently, she has been pressing Harvard to launch a prison education program for people in Massachusetts correctional facilities. All of Harvard’s Ivy League peers except Dartmouth already offer courses or degree programs in prisons near their campuses, taught by faculty members and students, and usually accredited through their schools of continuing education or local community colleges; Hinton particularly admires the programs run by Columbia and NYU.

Education for the incarcerated and the formerly incarcerated has become a central concern in her work. “It’s a huge part of her commitment to bringing her scholarship into the real world of criminal justice reform,” Khalil Gibran Muhammad says. In her book, she notes that people in prison are among the least educated in society, and that lack of education is a stronger predictor of future incarceration even than race. Taking classes while behind bars, meanwhile, has been shown to markedly reduce recidivism rates, and prisons with education programs are often safer than those without.

Bringing education into prisons is an affirmation that the people locked up inside are human beings capable of self-knowledge, that they deserve the chance to grow.

But for Hinton, the imperative goes deeper. Bringing education into prisons is an affirmation that the people locked up inside are human beings capable of learning and self-knowledge, that they deserve the chance to grow. That includes, she adds, those sentenced to life without parole: “It is a human right,” a good unto itself.

Which brings her back to Harvard. Universities, she argues, are uniquely positioned—and morally bound—to invest in prison education, an investment she believes is key to ameliorating the incarceration crisis. “Supporting faculty research is not enough to actually change lives,” she says. Education helps not only by improving the well-being of those imprisoned, but also by cultivating their expertise: “People who have been through this system firsthand really need to be at the forefront of a lot of the policy discussions that we’re having about these issues,” Hinton says. “And colleges and universities can begin to facilitate these kinds of conversations.”

In March 2018, Hinton co-organized a conference, “Beyond the Gates,” proposing a Harvard-run prison education program. The University has not yet taken up that proposal, a point of frustration for Hinton and the other organizers; but “We all knew this was going to be a long-game situation,” says Elsa Hardy, a Ph.D. student and Hinton advisee who researched Harvard’s history of prison education for the conference (and is planning a career in prison education). “We wanted to hear from people who have been incarcerated and have had their lives changed by these programs, and from practitioners who have developed them,” says conference co-organizer Garrett Felber, a University of Mississippi historian who was a Warren Center visiting scholar that year. “To say, ‘Look, this is what can be done.’” Muhammad moderated a panel of formerly incarcerated speakers now working in prison education and in re-entry efforts for those released. They talked about the hell they’d been through and the college courses they’d clung to like a raft.

The following evening, listeners filed into Sanders Theatre for a discussion among activists, scholars, and former inmates (including Jones). “I am one of 70 million Americans who have a criminal conviction,” said Bard College graduate Darren Mack. “Education is meant to transform, to change us, and to change the world,” said conference co-organizer Kaia Stern, a Harvard Graduate School of Education lecturer and director of the Prison Studies Project, which for several years led “inside-out” courses bringing students from Harvard and Boston University together with incarcerated students to attend classes.

Conant University Professor Danielle Allen, director of the Safra Center for Ethics, whose 2017 memoir Cuz told the story of her cousin who spent more than a decade in prison and was murdered a few years after his release, delivered the introductory remarks that night. “It is possible to live in a different world, to think of wrongdoing and rehabilitation differently,” Allen said. “It’s not crazy; it’s not a utopia.”

* * *

Recently, Hinton’s research has returned her to an old question, and to a place that in some ways feels like home. For the past few years, she has been working with the police department in Stockton, California, a small city in the Central Valley with a gun-violence rate higher than Chicago’s and a black population that has historically distrusted the police. She was awarded a Carnegie fellowship to spend this academic year there; she’s been helping the department conduct a “reconciliation process” with the community, uncovering and addressing longstanding sources of tension. In return, Chief Eric Jones granted her access to decades of police administrative files—exactly the kind of archive that could help put together a history of gang violence. She’s still in the early stages of her research, but, she says, “I’m trying to tell the history of a city in order to historicize violence.” She pauses for a moment, then adds, “I mean, I’ve always wanted to write about Saginaw”—and in Stockton, she sees elements of her cousins’ hometown: segregated, struggling economically, with areas of deep poverty that are heavily policed.

“In some ways these places, like Stockton and Saginaw and Ferguson, this is what much of America looks like,” she continues. “These cities have a lot to teach us about how we got to where we are.”