The penultimate chapter of sociologist Roberto Gonzales’s book Lives in Limbo—the chapter he calls the most painful and gripping to read, the one that would be its climax, if the book were a work of fiction—opens with a story about two factory workers on an auto-parts assembly line. The men are friends, both in their late twenties, and both undocumented immigrants. Like everyone else in Gonzales’s book, they’ve spent most of their lives in the United States. One of them, Jonathan, never finished high school, while the other, Ricardo, has a college degree in political science and a master’s in management. “He shouldn’t even be here,” Jonathan says, sitting at a lunch table in the factory’s crowded break room. But Ricardo disagrees. “You see, this right here is right where I’m supposed to be,” he tells Gonzales. “It’s probably where I’ll be in five years.” He has figured out what Gonzales’s research notes have inexorably begun to show: that no matter what his education, or talent, or work ethic—or intrinsic “Americanness”—the thing that defines his life is his illegality.

An ethnographer as well as a sociologist, Gonzales is a professor of education and director of the Immigration Initiative at Harvard. He studies the lives of young undocumented immigrants like Jonathan and Ricardo, people who were brought, or sent, or smuggled into the United States as children, often before they were old enough to remember, and who then grew up here, in a state of perpetual in-between. His phrase for this kind of existence is, “Ni de aquí, ni de allá”: from neither here nor there. He has spent two decades (three, if you count his previous life as a youth worker in Chicago’s immigrant neighborhoods) amassing arguably the world’s most comprehensive data set about a population that, up until then, had never been closely studied.

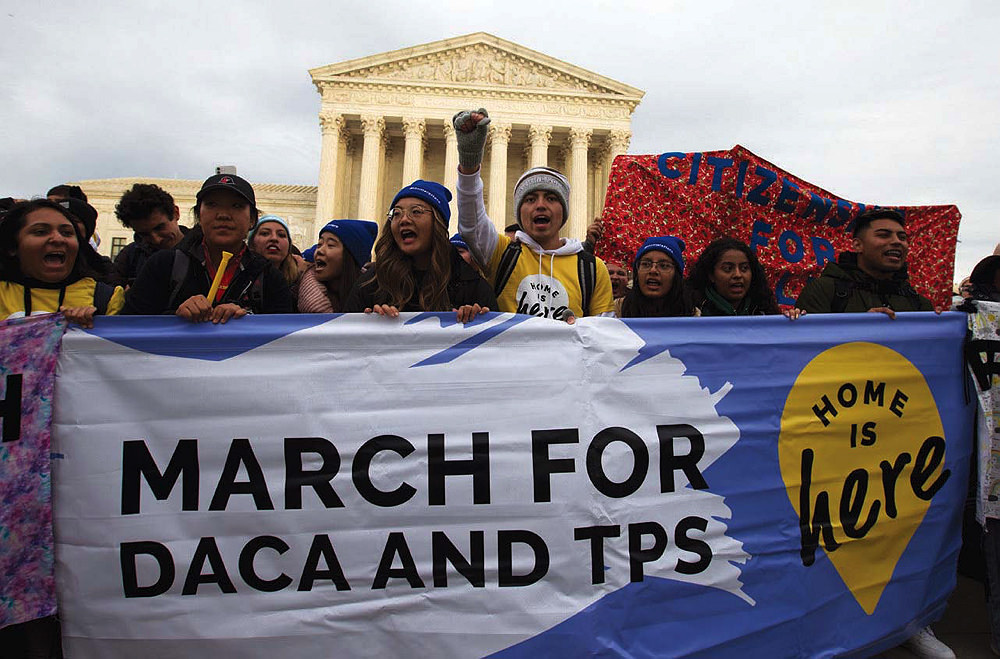

Demonstrators march in front of the U.S. Supreme Court last November, ahead of oral arguments in the case to decide DACA’s fate.

Photograph by JOSE LUIS MAGANA/AFP via Getty Images

Gonzales lays out this data in Lives in Limbo: Undocumented and Coming of Age in America, published in 2016—although, truthfully, data feels like too narrow a word. “At its heart, this research is about stories of belonging and wanting to belong,” writes Jose Antonio Vargas in the book’s foreword. A Pulitzer-winning journalist and immigration activist, Vargas is himself an undocumented immigrant. “Alexia, Chuy, Pedro, Gloria, and the others in this book are real people whose lives have been profoundly shaped by our complex and unpredictable immigration system.”

The research for Lives in Limbo began in 2002, when Gonzales embarked on what would become a groundbreaking 12-year study, closely following the lives of 150 young people in Los Angeles who had grown up in America but were here illegally. The vast majority were born in Mexico; when Gonzales first encountered them, they were somewhere in their twenties, and from his rich narratives of their unfolding lives, a complex picture emerges. At first, and for a long time, their experience of life in America seemed to be one of inclusion. A 1982 Supreme Court decision, Plyler v. Doe, permitted undocumented immigrants to attend public K-12 schools—“the most powerful institution for their age,” Gonzales says—and that mandate came to include after-school programs and summer activities. Undocumented children play sports and join clubs with their American-born classmates. “There are really no restrictions,” Gonzales says. Absorbing American sensibilities and aspirations, the idea of the American dream, they become cultural citizens, if not legal ones.

The crash comes in stages. Perhaps in early high school, they apply for driver’s licenses, or summer jobs, and discover they cannot get one without a Social Security number. For many, Gonzales found, the news that they are not legal residents comes as a shock. A few years later, applications for college, or for financial aid, present similar problems. The vise starts to close. As their American friends move forward into postsecondary education and careers and households of their own, most undocumented young people find themselves tripped up again and again—and in the end, permanently—by the limits of their immigration status. “The transition to illegality,” Gonzales calls this process. One of the young women he interviews has another name for it: “waking to a nightmare.”

Over time, Gonzales watched the group of 150 split into what he terms “early exiters”—people like Jonathan who never made it past high school, because of poverty or disillusionment or the raw demands of survival—and “college goers” like Ricardo. These divergent paths launch young people on starkly different trajectories throughout early adulthood, but by the time they reach their thirties, Gonzales found, those trajectories converge. And so it was that Jonathan and Ricardo were eating lunch together in the break room of the factory where they both were paid in cash for work that was backbreaking and mind-numbing, surrounded by the chatter of their immigrant co-workers.

“Hustling for a dream”

Lives in Limbo cemented Gonzales’s academic reputation. The book won the 2016 C. Wright Mills Award from the Society for the Study of Social Problems, a prize named after the postwar American sociologist who insisted early on that social scientists should not merely be theoreticians and disinterested observers, but moral actors bearing social responsibility. Other honors rolled in from academic organizations across a range of disciplines: anthropology, social work, educational research, law and society. “The most important thing I can say about Roberto is, read that book,” says Donald Graham ’66, the former longtime publisher of The Washington Post, who co-founded TheDream.US, an organization that provides college scholarships to undocumented students. “As a very old-fashioned American, somebody who believes in this country, Lives in Limbo is very hard reading. But it’s important reading. Roberto makes clear how truly impossible the situation of undocumented families is.”

The response from young undocumented immigrants themselves was even more powerful. People whom Gonzales had never met wrote and called, wanting to share their own stories of growing up in-between. Four years later, they still do. Those who had been his research subjects wrote and called too, asking when the book might be translated into Spanish: they’d been reading it to their families, they told him, so their parents could better understand what they’d been through. “Because, see, the road they travel is so different from their parents,” Gonzales says. “Adult migrants have a very consistent experience with being undocumented.” Exclusion, for them, is the starting point. “As soon as they arrive, they’re learning the rules of this country, what it will take for them to get home safe at the end of the day, to feed their families, to stay hidden, to keep quiet.” A lot had been written about that experience already. Now, for the first time, their children saw themselves reflected back.

It felt that way for Vargas. He was 12 years old when his mother put him on a plane from the Philippines to California, where his grandparents, both U.S. citizens, were waiting for him. Now 39, he has not seen his mother since that day. He spent his adolescence in Mountain View, and for him the waking-to-a-nightmare moment came at 16, when he presented what he thought was a green card at the DMV to apply for a driver’s permit and was told it was fake. He remembers tearing home on his bicycle to confront his grandfather about the lie.

Vargas managed to hide his undocumented status until he was almost 30. He finished high school and went on to college and then found a job at The Washington Post, where he won a Pulitzer covering the 2007 school shooting at Virginia Tech. In 2011, unable to bear the strain of his dual life any longer, he “came out” as undocumented in a New York Times Magazine essay and started a nonprofit, Define American, which advocates for immigrant rights and a rethinking of national identity. “I think when we look back at this time,” he says, “Lives in Limbo is going to be one of those landmark pieces of work that you can give to somebody, a grand-niece or grand-nephew, and say, ‘Look, this is what happened.’ In some ways, Roberto is chronicling one of the most important stories of modern American history.”

Karla Cornejo Villavicencio, one of Harvard’s first undocumented graduates: “I just felt so lost.”

Photograph courtesy of Karla Cornejo Villavicencio

It felt that way for Karla Cornejo Villavicencio ’11, too. Now a Yale Ph.D. student in American studies whose first book, The Undocumented Americans, came out in April, she was one of the first undocumented immigrants to graduate from Harvard. Back then she felt trapped, alone, and invisible on campus. The mental-health toll of that experience, and the deep depression and anxiety it triggered, took years for her to understand. Gonzales’s work helped. “I felt so seen through his research,” she says. Most other books she’d read on immigrants seemed written for someone else. But with Lives in Limbo, “I read that, and I thought, ‘That’s what I was going through.’ I had spent my entire life hustling for a dream, trying to get out, trying to save my parents, and then I made it to Harvard, and”—like so many of his research subjects—“I knew I was about to crash.” Even with an Ivy League degree, she had reached a familiar precipice: her undocumented status, she knew, would put most jobs—and every good job—out of reach. “Honestly, I just felt so lost.”

“A claim to personhood”

Depressed, anxious, lost. One unanticipated but unsurprising through line in all Gonzales’s work, from Lives in Limbo to his current research—to his teaching at Harvard, which centers in part on the educational needs of undocumented immigrants—has been the psychological and physical consequences of living without legal status. In the book, he describes a whole constellation of maladies, which he came to recognize, he writes, as symptoms typically linked to unresolved grief: headaches, toothaches, ulcers, high blood pressure, insomnia, overeating, undereating, chronic sadness, chronic fatigue. Some respondents drank too much, and others took drugs. One woman told Gonzales that she’d gone to the emergency room twice with pain so intense it felt like a heart attack. “I was overwhelmed by how consistent these manifestations were, and how severe the suffering,” Gonzales says. “Initially, I didn’t expect this—I was focused on questions of social mobility. But there was no mistaking what was happening.”

The finding was another answer to the question he had started out with: how policy shapes everyday lives. And more recently, he has made it an intentional research focus. Last summer, Gonzales completed fieldwork on a seven-year study of DACA (the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program), which shielded beneficiaries from deportation and granted provisional rights that allowed them to get driver’s licenses, apply for jobs, and go to college. There are now as many as 800,000 enrollees. After the DREAM Act, which proposed a pathway to citizenship, failed in Congress, President Barack Obama launched DACA by executive order in 2012. The idea was to tide things over until legislation could resolve their predicament more permanently; instead, five years later, the Trump administration announced it was ending the program altogether. That decision sparked a flurry of litigation, and late last year, the U.S. Supreme Court heard oral arguments in a lawsuit seeking to preserve DACA. As of press time, a ruling was expected any day. [Update 6/18/20: In a 5-4 decision released on June 18, the Supreme Court rejected the Trump administration’s effort to end the program. Chief Justice John Roberts ’76, J.D. ’79, wrote the majority opinion: “We do not decide whether DACA or its rescission are sound policies. We address only whether the agency [the Department of Homeland Security] complied with the procedural requirement that it provide a reasoned explanation for its action.”]

In 2013, Gonzales and several colleagues surveyed almost 2,700 DACA beneficiaries nationwide, following up in-depth with about 500 respondents in six states: California, Arizona, Georgia, South Carolina, Illinois, and New York. The data show clearly, he says, that in almost every way, the program has made people’s lives better, sometimes dramatically so. Immediately, people started getting driver’s licenses and health insurance. They opened credit-card and bank accounts; they started making more money. (Society benefits from having their lives regularized, too.) Just 16 months into the program, 59 percent of respondents reported having found new jobs. “They’re able to chart out occupational pathways that match their education,” Gonzales says. They were able to go from college to graduate school, medical school, law school—trade school. “Even more modestly educated people were finding on-ramps back to GED programs, to community college, to occupational licenses, and using those programs as stepping-stones to better things.” These recipients, he says, are some of DACA’s biggest success stories.

The effects rippled out to families too, as DACA beneficiaries were able to contribute more to household expenses, to rent and mortgages. They were able to drive relatives to and from work. They endured fewer headaches and toothaches, less depression and anxiety. “People felt a greater sense of belonging,” Gonzales says. “Having this identity as a DACA holder allowed them to stake a claim to personhood, to membership in this society.” In 2018, he testified about these findings before the Senate Judiciary Committee.

The other side of all that, of course, was the Damoclean uncertainty that hung over the whole project. “What does it mean to implement a policy that is temporary and partial?” wondered Gonzales. And after DACA’s repeal, he found himself asking an even more profound question: “What does it mean to have an expiration date?”

“An opportunity to fill in a void”

It has been a difficult few years to be an immigration researcher. Immigration bans, deportation raids, and family separations at the border, ever-tightening restrictions on refugees and asylum-seekers and green-card applicants: President Donald Trump’s agenda on immigration has been his most consistent pursuit since taking office, the campaign promise he’s tried hardest to keep. For scholars like Gonzales, it forces a difficult calculation. “On the one hand, there’s a tremendous responsibility to document what’s happening,” he says. But there are new hazards as well. Undocumented immigrants are “arguably more vulnerable now than at any other point when I’ve been doing this research.” Two years ago, Gonzales abandoned a plan to interview parents and siblings of DACA beneficiaries, because it would have meant collecting addresses and contact numbers. He decided it wasn’t worth the risk.

Undocumented immigrants are “arguably more vulnerable now than at any point when I’ve been doing this research,” Gonzales says.

At Harvard, meanwhile, the DACA repeal sparked an act of protest that led eventually to the formation of the Immigration Initiative. In early 2018, Gonzales and two colleagues—Winthrop professor of history and of African and African American studies Walter Johnson and professor of history Kirsten Weld—organized a series of seminars with immigration lawyers, activists, educators, undocumented students, and Harvard workers affected by recent changes to immigration policy. The capstone event, in early March, was “A Day of Hope & Resistance”: 12 hours of workshops, discussions, performances, and open-mics, convening at 10 a.m. in Memorial Church and closing with a candlelight vigil and a concert finale. Speakers and performers included Latinx artistic luminaries: hip-hop duo Rebel Diaz, Los Angeles rock group Quetzal, migrant poet Sonia Guiñansaca, feminist rapper Audry Funk, jazz singer Esperanza Spalding, and undocumented immigrant poet Yosimar Reyes.

Turnout was enormous at almost every event. “So that taught us that there was huge interest in this subject on campus,” Gonzales says. And it gave him the idea to try something bigger: in October 2019, the Immigration Initiative launched. Housed at the Graduate School of Education (GSE), it reaches University-wide and rests on three basic pillars: a speaker series; a research fellowship for graduate students working on immigration-related dissertations in fields from education and history to public health and government; and a collection of short issue briefs, aimed at policymakers, distilling academic research on subjects like family separation, toxic stress, and the ripple effects of deportation in schools. Meanwhile, the organization’s website functions as a clearinghouse for other immigration events, performances, exhibitions, and courses across campus, and provides links to student organizations, resources for immigrants, and volunteer opportunities beyond campus.

“It’s been very healing” to work for the Immigration Initiative, says Ariana Aparicio Aguilar.

Photograph by Jon Chase/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

The initiative also serves another, less overt but necessary, purpose, says research assistant Ariana Aparicio Aguilar, Ed.M. ’19, a DACA recipient born in Mexico City who arrived in California with her family at four and came to Harvard three years ago to study with Gonzales. “It’s an opportunity to fill in a void,” she says, “to back up what the University as a whole is not doing already for undocumented students.”

Some colleges, especially those with larger DACA populations, have stand-alone campus centers for immigrant students, with full-time staff to help the undocumented navigate immigration laws and to connect students to other resources. At Harvard, undocumented students receive assistance from the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Law Clinic at the Law School, and a training program called UndocuAllies works to educate faculty about the basics of helping undocumented students, but that exists only at the GSE, and is run by students, who cycle in and out. Student activists have long argued for more comprehensive resources for the estimated 100 DACA beneficiaries on campus. Gonzales agrees. “We need something more systematic here,” he says, and especially now, with immigrants under greater threat from government policy. “I know it’s hard on a decentralized campus.”

“Some of them would just disappear”

Gonzales’s own family goes back generations in Colorado and New Mexico. He grew up in Colorado Springs, a college and military town on the eastern edge of the southern Rockies, the seat of one of the most conservative urban counties in the country. As a child, he and his sister were mostly raised by his mother, who often held two or three jobs to keep the household afloat. “She had a very keen understanding of inequality,” Gonzales says. “She taught me to hate injustice.” Meanwhile, he played football. He was small and wiry, but fast, and as a high-school running back, promising enough to attract attention from college recruiters. But in the last game of his senior year, he blew out his knee, and the injury ruined his hopes of an athletic scholarship. “It was devastating at the time,” he says. He applied to colleges more or less randomly after that. “A working-class kid—I was just trying to figure out how to navigate.” But his grades were good, and when nearby Colorado College offered financial aid, he enrolled.

Almost immediately, he was drawn to sociology. There was something profound about being able to discern structures and patterns in the jumbled complexity of human society, to put words and names to lived realities that often went unexpressed or unexamined. Sometimes, he found himself disquietingly reflected in the field’s taxonomy, but there was appeal in that, too: “It was in some ways really empowering, and in other ways kind of scary. I was looking at my life through the lenses of a textbook: poor, working-class, single mom, person of color, all these things.”

During his junior year, in 1991, Gonzales took part in an urban-studies program in Chicago and spent a few months interning at a settlement house on the city’s west side. He tutored kids, played sports with them—“Anything that I could do. I would go anywhere I was needed.” The surrounding community was predominantly Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Polish, and he loved being there. After the internship ended, he stayed on for several extra weeks. (Afterward, he spent part of the summer working at a small island resort in Maine, an experience that hammered home a lesson about the gulf between rich and poor. When a hurricane hit that August, downing trees and knocking out electricity, the resort tried hard to make sure its guests were never inconvenienced. “So there we were, day after day,” Gonzales remembers, “trying to seamlessly serve breakfast, lunch, and dinner to these very wealthy families after this huge, devastating storm. We were washing dishes in the lake.”)

After graduation, he returned to Chicago as a full-time youth worker and stayed for 10 years. It was there, he says, that he began to see how powerfully immigration status affects children’s lives. In Colorado, he’d known plenty of Mexican Americans, but, like him, they mostly were third- and fourth-generation citizens. In Chicago he kept seeing neighborhood kids hit dead ends. Without legal immigration status, it was hard—or impossible—to build productive lives. Gonzales and his colleagues were at a loss. “People were really blind to this stuff back then,” he explains. “We were seeing this growing demographic come of age right in front of us, and there was no academic work at the time, no evidence base informing best practices on how to help these kids. So, teachers, counselors, social workers, healthcare professionals, community institutions—we were really powerless. There were so many stories of young people in our program dropping out of school because they’d become too disillusioned. And then some of them would just disappear.”

One was a boy he calls Alex. Gonzales met him when he was seven and his family—Mexican mom, Guatemalan dad, and an older brother—had been in the United States for four years. Chicago was the only place Alex remembered. He had a talent for art, and as he grew up, Gonzales and his colleagues supplied him with paints and sketchbooks, enrolled him in classes. Eventually, they made plans to help him attend a private high school for the arts and raised a semester’s worth of tuition to get him in the door.

“Are you telling us this boy is an illegal Mexican?” Gonzales still winces at those words.

That’s when everything went wrong. Filling out the application for admission at his family’s kitchen table, Alex hit his waking-to-a-nightmare moment: he had no Social Security number. Before then, it had never fully dawned on him, Gonzales says, that he, like his parents, was undocumented. The next few days were filled with panic. Gonzales wrangled a sit-down with the school’s admissions office, but midway through that meeting, with Alex’s portfolio sprawled out across the desk, they began asking questions: “‘Are you telling us this boy is an illegal Mexican?’” Gonzales still winces at the memory of those words. He did his best to answer, “but it was clearly hopeless.”

After that, Alex unraveled. Angry and disillusioned, he withdrew. During his first semester at the neighborhood high school, he found out that he wouldn’t be able to take driver’s education with his classmates and left school not long afterward. He started hanging out with guys from a local gang, and then one afternoon, as he was walking down the street with a friend, three men in masks jumped out of a van and shot him dead.

Gonzales was deeply shaken. “It just really….” He pauses. “It took a toll on me.” In the days and months that followed, he struggled to understand what had happened. Looking for answers, he found his way back to sociology.

“It became their identity”

He had one foot in academia already. For three years, he had been taking night courses at the University of Chicago to earn a master’s in social work. He’d also started teaching classes on youth immigration in the same urban-studies program that first brought him to Chicago. Then, at 32 years old, he headed west, to a doctoral program at the University of California, Irvine.

His dissertation fieldwork began almost as soon as he arrived, and almost by accident. Restless in the suburban placidity of Irvine, he ventured out to Santa Ana, a community that felt more like those he’d known in Chicago: Latino, lower-income, lots of immigrants. Volunteering at a social-service agency that specialized in second chances for kids pushed out of the system, Gonzales started hearing about students who were undocumented. “And their stories were eerily similar,” he says: “They had moved to California with their families at six months old, or two years old, five years old.” They’d grown up in local neighborhoods, were educated in local schools alongside American-born friends, took part in summer camps and after-school sports. “And then, at a pivotal time in their lives—14, 15, 16 years old—they were hitting a wall.…You could watch them suddenly arrive at this understanding of themselves as undocumented immigrants, and the stigma that carried. It became their identity.”

All at once, his research had focus and urgency. Gonzales began spending time in social-service agencies across Los Angeles, volunteering in after-school programs, tutoring programs, church groups, men’s groups. He got to know community workers, teachers, parish priests. He talked to parents, families, kids. “I wanted to establish myself as somebody who was giving more than I was asking for,” he says. “In Chicago, I had seen a lot of research relationships gone wrong.” For many of the subjects who ended up in his dissertation, he let a full year pass before turning on a tape recorder.

He earned his Ph.D. in 2008, but the project continued for another six years. “I was just keeping in touch with people,” he says. “And I was hearing some horrific stories. And so I just kept scheduling interviews.” He joined the faculty at the University of Washington, and then the University of Chicago. In 2013, he arrived at Harvard, with a manuscript under way. By the time Lives in Limbo was published three years later, American political rhetoric had taken a sharp turn against immigration.

In his current research, Gonzales has been thinking about place. “More so than ever, where one lives matters a great deal,” he says: it can mean vastly divergent legal and social landscapes, the difference between having access to public transit or having to drive an hour for social services. “And layered on top,” he says, “you have legacies of embracing immigrants, or legacies of segregation and hostility.” In the absence of federal immigration reform, states, counties, and municipalities formulate their own responses. Some declare sanctuary cities and allow driver’s licenses and in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants; others pass anti-sanctuary bills and ramp up cooperation between local law enforcement and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), the federal agency that carries out deportations.

Gonzales and several colleagues are conducting a study on educators’ responses to the current political moment: how they deal with immigration issues bubbling up in classrooms. One goal is to identify the best practices that eluded him and others 20 years ago in Chicago. “We’re still in the early stages, but we’re learning that best practices look very different across the country.”

The researchers have visited school districts in the suburbs of Chicago and in south Texas, near the Mexico border. Last year they headed to a rural district in Georgia to talk with administrators about the study. “And they told us, ‘We don’t have immigrants in our schools.’” When Gonzales pointed to local statistics on foreign-born students and families, “they said, ‘Oh, you mean the Hispanics.’…Now, this is an interesting thing. My interpretation is that it’s a way for them to support their students but also still be aligned politically with a rhetoric that is anti-immigrant. If you have this disconnect, this dual reality, then they’re not really immigrants. These are our students.” It reminds him of recent news stories describing the shock some conservative voters felt at seeing the harsh immigration policies they’d supported being enforced against undocumented people they knew, pillars of their own communities. “It’s fascinating,” Gonzales says. “You boil this down to individual stories, and it’s not really them. It’s people.”

“I am from uncertain futures”

Every fall, Gonzales teaches a course called “Contemporary Immigration Policy and Education Practice,” drawing in part on his research into the forces that shape young immigrants’ lives. It’s a popular class, open to undergraduates as well as graduate students. Last year, Andrew Perez ’20 was one of a dozen or so from the College who signed up. A U.S. citizen who is the son of Mexican immigrants, Perez grew up in a mixed-status family, his own version of living in-between. Two summers before he arrived in Cambridge, he spent a week on a humanitarian and educational trip for teens to Nogales, Mexico, where he met a man who had recently been deported, leaving three daughters behind in the United States. As they talked, Perez realized that they’d lived five minutes apart in California. “I didn’t signal,” the man said, when Perez asked how he had been apprehended. “I made a left and I didn’t signal, and that’s why they stopped me.” Recalling that conversation now, Perez stops short. “Something as simple as that—it really hit me.” When he arrived at Harvard, he found his way to Gonzales.

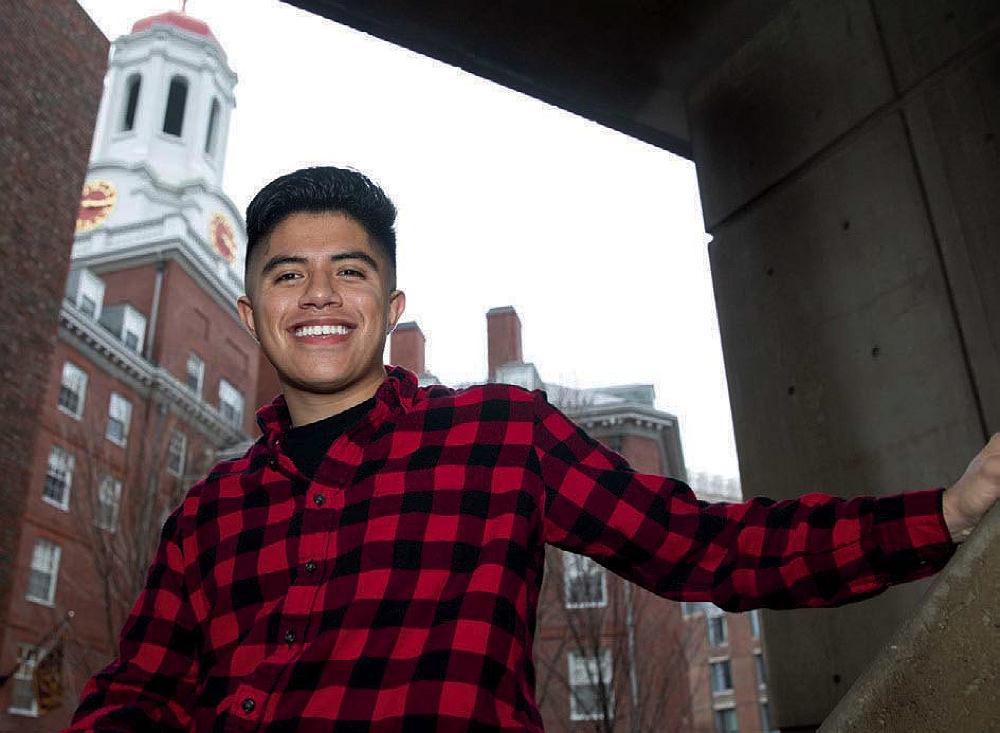

The son of Mexican immigrants and a U.S. citizen, Andrew Perez ’20 grew up in a mixed-status family, his own in-between.

Photograph by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Public Affairs and Communications

In last fall’s class, the first day’s assignment was for each student to write what Gonzales calls a “home poem,” modeled after Kentucky poet George Ella Lyon’s “Where I’m From” (her first three lines: “I am from clothespins, / from Clorox and carbon-tetrachloride. / I am from the dirt under the back porch”). “It’s a poem that identifies the speaker in a particular place and culture and time,” Gonzales says. He makes this same assignment on the first day of every course he teaches. He always writes one, too. Then at the end of class, they all read aloud what they’ve written. “It makes us all vulnerable together, and people find commonalities—culturally, linguistically, in family history. It speaks really powerfully to who our students are, where they come from.”

That assignment meant a lot to Perez. “People have such complex lives,” he says. “And everyone has their story.” He keeps his own poem stored on his phone, alongside photos of his Harvard roommates, his twenty-first birthday, a cousin’s quinceañera, two childhood friends recently lost to suicide, his young nephews in their Harvard T-shirts and hats. Now he reads it aloud again, his voice thickening as he reaches the last two stanzas:

I’m from wrinkled faces that ask if I have eaten

Who want to see me but are scared of planes

I’m from family that has left and stayed

And who I hope will welcome me back

I am from uncertain futures but hopeful spirits

I am neither and both from there and from here

And one day I will be home