They were prepared. Alexandra Petri ’10, a columnist for The Washington Post, memorably skewers the pompous and powerful. Nothing Is Wrong and Here Is Why, her new collection, reveals her as a contemporary Cassandra. A March 16, 2017, essay on “A New Foundation for American Greatness” (the title of the first Trump budget) noted that the lengthy document was widely criticized for cutting “needed programs in favor of increasing military spending by leaps and bounds.” Petri helpfully explained how this would work out. In an especially prescient passage, she wrote: “National Institutes of Health: We are decreasing funding because in the future we will cure disease by punching it, or, if that fails, sending drones after it. Also, we will buy more planes and guns to shoot airborne viruses out of the sky.”

Mission accomplished?

Leader cults. A scholarly prognostication has unhappily proved less potent. The Memorial Minute for Williams professor of history and political science Roderick MacFarquhar was presented at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences meeting late last winter—with a wary eye toward the gathering pandemic (which of course involved China). MacFarquhar is best known for his trilogy The Origins of the Cultural Revolution, the final Maoist catastrophe imposed on the People’s Republic.

At a symposium a few years ago on the country’s current leadership, the minute noted, he observed that “Xi Jinping has transformed China at an amazing pace. Maoist institutions and values are being restored, though.…So the Chairman’s portrait will continue to hang in Tiananmen, and citizens will continue to be shepherded into his mausoleum.” Despite the continuing dead weight of the founder-leader’s cold hand, the text of the minute observed, MacFarquhar somehow found room for optimism: “People as dynamic as the Chinese…are not going to be ruleable from one center, one party, or one person…for very much longer.”

That hopeful prophecy has been unfulfilled—at least so far.

Fiscal futures. Alberto Alesina, the late Ropes professor of political economy, may have been best known for advocating fiscal policies disciplined by austerity—ideas lately countered by trillions of dollars of emergency spending worldwide to combat pandemic-driven economic lockdowns. But his ideas perhaps retain a larger purchase. In an extraordinary full-page tribute, The Economist’s Free Exchange columnist called him “an economist of politics and culture” who sought to understand “why some countries are rich and others poor” by “looking beyond prices and GDP” to “historical, sociological, cultural variables” that influenced the choice of certain institutions and fiscal policies. Thus he explained why the United States spent less on welfare and a social safety net than Europe (resulting, for instance, in miles-long queues at American food banks this past spring).

Alesina worried about how diverse political systems seemed vulnerable to incurring deficits. The current crisis will pass, but the magazine warned that his concerns did not vanish with his much-too-early death while hiking, in May, at age 63: “As COVID-19, rising healthcare costs, and an older population cause debt to mount, his arguments may soon seem more relevant than ever.”

Career serendipity. Liberal-arts institutions say they prepare youngsters for unpredictable futures. Harvard admissions may want to profile Brynn Putnam ’05, a Slavic languages and lits concentrator. With everyone sheltering in place, The New York Times reported on June 30 that Mirror—a home-fitness start-up that streams workout routines—had been acquired by Lululemon, purveyor of “expensive athleisure and active wear,” for $500 million. According to the Times, Putnam, a former ballerina, launched Mirror in 2018, raising $72 million from investors. Its new CEO sees the deal as capitalizing on a new industry: customers’ “accelerated…adoption of in-home sweat.”

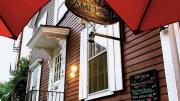

COVID closing: A Harvard Square casualty is Café Pamplona, which went out of business in late spring after a 62-year run.