For most Americans, Nazi Germany represents something from a history book: alien, remote, the stuff of nightmares. For Martin Puchner, Wien professor of drama and of English and comparative literature, who grew up in Nuremberg before moving to the United States for graduate school, the Nazi era is not just recent history, but also an indelible part of his family’s past. In his recently published memoir, The Language of Thieves, he guides readers through a centuries-spanning story of his family and home country, told through a most unlikely subject: Rotwelsch, the language spoken by vagrants, beggars, thieves, and other itinerant outcasts throughout central Europe for hundreds of years.

Rotwelsch is likely not familiar even to most language enthusiasts: the language was always meant to be secret—a blend of German with words from Hebrew, Yiddish, Romani, and other tongues spoken in the region, used in ways that did not always correspond with their “real” meanings, in order to evade authorities. But Rotwelsch could be just as clever and playful as it was cryptic. “Prison” was schul (borrowed from the German for “school”), Puchner explains; to make an escape was an hasn machn (“to make a hare”). To help each other navigate a hostile landscape, Rotwelsch speakers etched secret signs, or Zinken, that look almost like cuneiform or hieroglyphics. Zinken could warn travelers of an aggressive dog, mark a safe place to sleep, or invite collaborators to join a church robbery.

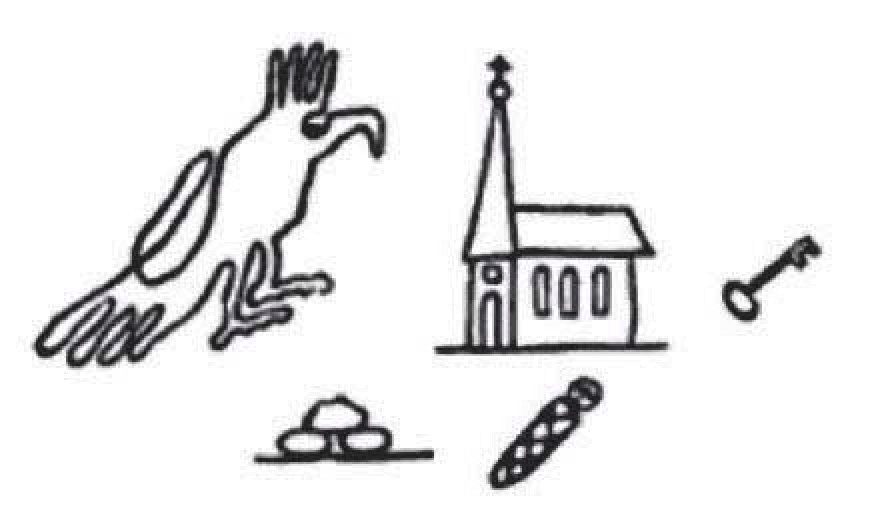

A Rotwelsch message translated by Puchner: A multilingual thief (parrot) plans a church robbery (key) on Saint Stephen’s Day (martyred by stoning). Meet here on Christmas Day (infant).

Zinken courtesy of Martin Puchner

Puchner’s father and uncle had had a lifelong fascination with Rotwelsch (the latter even wrote poems and translated the Bible, Shakespeare, and Goethe into the language), but for a long time, he hadn’t really known why. A clue came when, as a Harvard graduate student, he made a shocking discovery. In Widener one day, he found the 1932 dissertation of his grandfather Karl Puchner, who had been an archivist and scholar interested in the history of names. Titled “Family Names as Racial Markers,” the thesis was a paranoid text arguing that “Jews had assumed German names in such numbers that one couldn’t distinguish a German from a Jew,” the younger Puchner explains. “It wasn’t just a matter of confusion, my grandfather said; it was a matter of outright deception. Jews had deliberately adopted Christian-sounding names to deceive.” Karl Puchner hated Yiddish, a blend of German and Hebrew (“like every mixture,” his dissertation read, “it is disgusting”), but he hated Rotwelsch even more—and believed its borrowings from Hebrew and Yiddish provided evidence of Jews’ criminality. Rotwelsch, much like Europe’s Jews, barely survived Nazi annihilation.

For centuries before the Nazi ascent, scholars, religious authorities, and police had tried to decode and root out Rotwelsch. Martin Luther sneered at traveling beggars as “foreign, Jewish, and deceptive, the work of the devil,” much as Puchner’s grandfather did. In the seventeenth century, Puchner writes, the Thirty Years’ War and subsequent Peace of Westphalia created a world of nation-states and borders (the foundation of today’s political order) that criminalized vagrancy. But the postwar devastation itself also uprooted huge numbers of people, giving rise to a larger, more entrenched Rotwelsch culture.

“My first reaction was deep shame,” Puchner writes of the revelation about his grandfather. “No one must know about this. As a German living abroad, I had always felt exposed, marked guilty by association… Whenever I told people that I had grown up in Nuremberg, there was a quick pause, followed by an ‘Oh….’ I could imagine the images that were flashing through my interlocutors’ minds, images of rallies and of Nazi flags.”

Yet Rotwelsch became an unexpectedly profound through line linking three generations of Puchner men. Martin remembers Rotwelsch speakers showing up at his house while he was growing up. As his uncle, Günter, realized, they were following an old Zinken carved into the foundation indicating they could find bread there. Martin Puchner was captivated by the language as a boy, and so Rotwelsch helped shape his linguistic proclivity: “it sounded worldly-wise, slightly cynical, suspicious of grand ideas and false words. In Rotwelsch, you knew that life was hard, that survival hinged on reading a faded sign, on making a quick getaway. The language captured an entire mode of life.” Puchner’s revelation about his grandfather also cast Günter’s devotion to Rotwelsch in a new light, as a form of atonement or revenge, perhaps, against the regime that wanted to destroy it.

Puchner’s father had once made a similar discovery about Karl: a 1937 photograph in which he appears smiling with his wife and young son, wearing a barely visible swastika button on his lapel. Perhaps his grandfather’s dissertation was a way of making himself useful to the Nazi regime, Puchner conjectures, of showing that his obscure field could be politically important. Nazi race science had failed to come up with ways of proving who was and wasn’t Jewish, so “[i]n the absence of biological criteria, names became crucial, and this was where my grandfather sensed an opportunity,” Puchner writes. “He was waving his flag as a historian of names, promising to deliver what biologists could not.”

Names indeed became central to the anti-Semitic, racist Nuremberg Laws (enacted in 1935), but not because of his grandfather, Puchner writes: “he wasn’t important enough for that.” Karl Puchner’s insignificance was probably what allowed him to escape denazification, and, despite investigations into when and why and how he joined the Nazi Party, to resume his comfortable post at the Bavarian State Archive, eventually becoming its director. Many readers will be broadly familiar with denazification, the process by which Allied nations purged Germany of Nazism after World War II, and with Germany’s later efforts to come to grips with its own history. The Language of Thieves offers a window into the psychological, emotional depths of an experience so common among living Germans: the discovery that one’s own parents or grandparents were Nazis.

“For me, reckoning with the Holocaust became the main reason for studying history,” Puchner writes; his home city was synonymous with crimes against humanity. Germany’s education system committed itself to Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or coming to terms with the past. Yet in his own family, the past was buried, secret. “History, even when it deals with the actions of people, tends to be distant and can therefore be absorbed without putting yourself, your own person, on the line,” he writes. “Family history is different: it challenges the instinct within families to keep things hidden, the desire to spare children from harmful knowledge about their parents or grandparents, the desire of children to love their parents despite what they might have done.”

Puchner’s dive into the history of Europe through Rotwelsch, a story of intermixture and mischief and survival (with mini Rotwelsch lessons throughout), is as much a revelation to a reader as it no doubt was to the author. Ever elusive, Rotwelsch seems to reveal more about those who study it—Karl the Nazi sympathizer, Günter the bohemian, Martin the German American—than about itself. This makes it all the more disappointing that Puchner’s text does not always follow through on its promises. Its connections between grandfather and grandson can feel too pat. Toward the end, a lengthy series of evocative but unfocused reflections on Puchner’s naturalization as a U.S. citizen and post-9/11 America feel disconnected from the narrative.

The book is at its best when Puchner surfaces what Rotwelsch, the scrappy, little-known thieves’ cant, has to tell us today: it’s “a reminder that our settled lives are not always possible, that there are people who are unsettled.…Every order, if it is to avoid becoming oppressive, must accept disorder, every border must accept porousness, every state must accept statelessness.”