Harvard’s adjustment to the coronavirus pandemic, from declining executive-education enrollment last winter to the depopulating of campus and shift to online instruction in mid March, began to show up in the University and Faculty of Arts Sciences (FAS) annual financial reports for the fiscal year ended June 30, 2020. But those results, released in late October and early November, respectively, foreshadow more severe challenges in the current year.

Harvard’s revenue declined—and is likely to fall further in 2021. And after reporting a consolidated loss equivalent to 1 percent of revenues last year, FAS forecasts a loss of as much as $112 million this year (conceivably 7 percent or more of revenues reduced by lower enrollment, which reduces tuition income and room and board fees). Such deficits, the report warns, “exceed the reserves available” to FAS and therefore necessitate “increased borrowing, decapitalizing the endowment, or making further cuts” of a structural nature.

The reports also provide context for understanding the performance of the endowment (which produced a solid 7.3 percent investment return; see “Timely Recovery,” November-December 2020, page 20) and Harvard Management Company’s (HMC) priorities, and contain data on the composition of the FAS faculty.

The University: From Surplus to Loss

In fiscal 2020, Harvard’s revenues fell 3 percent, to $5.4 billion, and it recorded an operating deficit of $10 million: sharp reversals from the 5.7 percent revenue growth and $308-million surplus logged in the prior year. The $138-million drop in revenue, accruing in the final 16 weeks or so of the fiscal year, reflects canceled executive education (which has been a half-billion-dollar business); room and board refunds; temporary closing of labs conducting sponsored research; and the cessation of events, reunions, parking, and rental income from University-owned properties. Given that revenue had been growing before then, vice president for finance and chief financial officer Thomas J. Hollister and treasurer Paul J. Finnegan calculated the actual effect was $270 million of “lost revenue”: annualized, a run rate approaching one-sixth of expected revenue.

Despite the emergency cost-savings imposed during the pandemic (building closures, for example), reported expenses remained largely on their pre-pandemic trajectory, rising 3 percent ($180 million for the year)—reflecting, in part, Harvard’s decision not to lay off or furlough staff members such as House dining-service and janitorial workers idled when campus facilities were closed. Travel expenses naturally fell, and other discretionary spending was reined in across the board—yielding aggregate savings of $155 million.

If there is a bright side to the $10 million of red ink, it is that two one-time accounting factors escalated the reported expenses substantially. Harvard recorded a reduction in the value (probably in nine figures) of the new science and engineering center in Allston (see page 13). That charge reflects its redesign for new tenants after construction was halted in 2009, resulting in changes to the original use of the enormous below-grade structure on which the complex sits. Accounting conventions require that such impairments be recognized when a facility comes into operation. A further charge was the $71-million accrual for the pandemic-prompted Voluntary Early Retirement Incentive Plan offered to staff members throughout the University. Nearly 700 eligible individuals, ranging up to the vice-president and staff-dean level, accepted; the accrual reflects the associated expenses (a year of salary as the incentive, plus related benefits costs). The program should result in operating economies as those staff members retire and positions are left open, restructured, or ultimately refilled. Absent these adjustments, the University would have reported a significant operating surplus for fiscal 2020, although not at the level of 2019.

Looking forward in mid fall semester, no one professed certainty about what the rest of fiscal 2021 would bring. Endowment distributions are being held level—a big change for faculties like FAS, which receives more than half its revenue from that source (which had been growing 4 percent to 5 percent annually). After an unexpected surge of current-use giving during the spring, perhaps in response to crisis appeals, the philanthropic outlook is uncertain, too. Meanwhile, online executive- and continuing-education programs are operating, but big-ticket in-person programs are on hold while the pandemic curtails travel—putting hundreds of millions of dollars of revenue at risk for Harvard Business School (HBS, which has four campus buildings for its executive programs), FAS’s Division of Continuing Education, and significant programs at the Graduate School of Education, the Harvard Kennedy School, and elsewhere.

Degree-program enrollment declined, too. HBS has about 260 fewer M.B.A. students enrolled than its typical two-year cohort of 1,800. The College enrolled 5,382 students, instead of the typical 6,600: a significant loss of tuition income (even after financial aid); and with less than one-quarter of those enrolled actually in residence, but distributed across the Yard dorms and Houses for safe distancing, it is collecting far less in room and board fees, but incurring a usual level of operating and maintenance expenses. Schools with large international enrollments, like the Kennedy School (HKS), may also be pressed. And the costs of high-frequency virus testing (three times weekly for resident undergraduates; once or twice weekly for faculty and staff members regularly on campus) and other safety measures are estimated at tens of millions of dollars annually. For details on spring residential plans, see News Briefs, page 26.

“The hardest part likely lies ahead,” Hollister and Finnegan wrote. For at least the current fiscal year, “Declining revenues and increasing costs is not a sustainable equation, but it is our near-term reality.” In other words, Harvard is likely operating at a deficit. Given huge uncertainties about public-health conditions and the spring semester, they emphasized liquidity (maintaining sufficient operating cash); reducing spending in line with revenues; and being “on the lookout for investment opportunities that will strengthen the mission for the future.” In November, the University announced that nonessential staff would work remotely through June 30, 2021—and that continued full pay for workers idled by the pandemic would be scaled down in January, and ended for contract workers (see harvardmag.com/covid-remote-staffing-20). As President Lawrence S. Bacow succinctly put it in a separate conversation, “No school is in distress—but all are feeling financial pressure.”

The Endowment

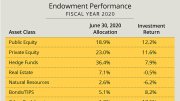

In the annual report, HMC provided some explanation for its previously announced results. The 7.3 percent investment return (comparing favorably among peers MIT, 8.3 percent; Yale, 6.8 percent; and Princeton and Stanford, both 5.6 percent), was driven by good public-equity results, including stocks (18.9 percent of assets, a 12.2 percent return) and hedge funds (36.4 percent of assets, 7.9 percent return). The strong performance relative to peers came despite a less-risky portfolio: HMC is relatively less invested, so far, in private equity, which has been a driver of many top endowments’ results in recent years. (See table opposite for asset allocation and returns.)

Real-estate, natural-resources holdings, and other real assets produced losses. HMC has significantly reduced such assets since N.P. Narvekar became CEO in December 2016 and began a complete restructuring, originally forecast to take as long as five years. The restructuring is now essentially complete, he reported—and performance has been better during that sweeping transition than he anticipated. Narvekar also signaled that disposition of remaining natural-resources and other underperforming legacy assets could be completed within the next two fiscal years.

From here, he wrote, performance will be most affected by asset allocation. The public-equity result this year may reflect unusually good performance by HMC’s external managers. Future returns, he noted, are likely to be correlated with the level of risk Harvard is comfortable assuming: a greater allocation to private equity ought to produce higher returns and long-term growth, but at the cost of a more volatile University budget. With Harvard’s overall dependence on endowment distributions rising to 37 percent of revenue this year (and FAS’s to 53 percent), determining the right level of risk is, as he put it, “a critical and complex collaboration with the University.” How the balance is struck “will guide future portfolio construction”—and exert a powerful influence, alongside HMC’s execution, on future endowment returns.

Read a detailed analysis of the annual report, including information on the endowment, at harvardmag.com/covid-fy-losses-20.

The Faculty of Arts and Sciences

Reflecting the highly unusual year, Dean Claudine Gay devoted much of her annual report to a chronicle of FAS’s response to the pandemic and the upwelling of protests over racial injustice: the de-densification of campus, the pivot to remote learning, an online Commencement, and academic work on race and inequity. She noted how many faculty members had been involved in planning for the fall semester, the resumption of limited College residence operations, and the application of FAS’s collective expertise to meet other challenges. “Though so much about our daily lives has changed,” she wrote, “the events of 2020 brought who we are at our core into high relief. The FAS is a community…alive with a profound commitment to our academic mission.”

The section of the report on the evolving composition of the faculty members who do that work is discussed in “Broadening the Faculty’s Ranks,” on page 18.

The financial report progresses from fiscal 2020 as affected by the pandemic (bottom line: not as bad as initially feared) to the “significantly greater effects” likely this year and in the future. Gay’s initial steps to reduce costs, announced on April 15, included freezing faculty and exempt-staff salaries; freezing searches; reviewing all proposed new staff positions; suspending and reviewing capital projects; and curtailing nonessential spending. Those measures, plus better than expected results from sponsored research and current-use giving, and less severe declines than feared in continuing education, trimmed the spring estimate of a consolidated loss exceeding $42 million down to a loss of $15.8 million (including an unanticipated $15-million accrual for early retirements). And aided by its fiscal 2017 agreement with the University to restructure long-term debt, FAS even generated a tiny bit of unrestricted cash during the year ($2.9 million).

But the outlook is grim. For fiscal 2021, FAS faces a cash deficit of $43 million, even with the debt restructuring (versus a pre-pandemic budgeted surplus of $27 million), and that operating loss of $112 million—despite reducing capital spending and debt service during fiscal 2020 and 2021 by $60 million. The budget assumes revenue losses and increased expenses (reduced tuition, room, and board, and costs for protective equipment, virus testing and tracing) of $120 million. Those figures are subject to revision depending on how the College can operate in the spring (the plan, announced December 1, is summarized in News Briefs, page 26).

In this context, the financial analysis concludes, FAS faces “several issues that transcend the COVID-19 pandemic”—in particular, “that continued heavy reliance on endowment distributions to fund the annual budget subjects FAS to…wide swings in financial results.” Given University projections of possibly constrained endowment distributions in light of expected lower investment returns, “a structural deficit may emerge, potentially of a magnitude that is too great to address with traditional approaches.”

At the November 3 faculty meeting, Gay said it was too soon to detail possible structural changes intended to get FAS back on sustainable footing, but an announcement the prior week from the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences (GSAS) suggested some of the pain points: reduced admissions for the 2021-2022 academic year, including “pausing” them for some programs entirely (see harvardmag.com/covid-gsas-fas-shifts-20). The immediate aim is to preserve available resources to support both current students, whose work has been disrupted, and future matriculants. But GSAS also intends to use this time to reconsider doctoral education more broadly, with the size of future cohorts disciplined not only by resources, but by an evaluation of the quality of advising delivered to students, diversity in admissions, and constraints within segments of the academic job market. This possibly transformative reassessment of Harvard graduate education reflects broader changes in higher education and doctoral training.

Unsurprisingly, some faculty members voiced concern about GSAS’s constraints. But Gay suggested the focus on such structural changes is intensifying now that the dimensions of FAS’s financial problems are known. At the same time, faculty members’ and students’ experiences with online teaching and learning, fresh approaches to classroom use and scheduling, and hybrid residential and remote degree programs may come to the fore, prompting innovative ways of overcoming pandemic-fueled resource constraints to sustain FAS’s, and Harvard’s, academic missions.

A full report on FAS appears at harvardmag.com/covid-fas-finances-20.