Why the Innocent Plead Guilty and the Guilty Go Free: And Other Paradoxes of Our Broken Legal System, by Jed S. Rakoff, J.D. ’69 (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, $27). A former federal prosecutor and private defense attorney, and a senior U.S. District Court judge for the Southern District of New York, Rakoff is dismayed by mass incarceration, wrongful convictions, coerced guilty pleas, and more. As he observes, “ordinary U.S. citizens have increasingly been denied effective access to their courts,” not least because of the shockingly high cost of retaining a lawyer and pursuing suits to their conclusion. He points to legislators, citizens, and judges themselves for urgently needed corrective actions.

In Search of a Kingdom, by Laurence Bergreen ’72 (Custom House/Morrow, $29.99). The prolific biographer has developed a thing for epic adventurers, nautical and terrestrial (Magellan, Marco Polo, Columbus). Next up: this new volume on Francis Drake, Elizabeth I, and “the perilous birth of the British Empire.” He knows and can tell a story. This one begins, “On the morning of December 13, 1577, Francis Drake, a pirate and former slaver, ordered his small fleet in Plymouth, England, to weigh anchor,” and then briskly covers a lot of territory, people, and of course foundational history.

Shaking the Gates of Hell, by John Archibald, NF ’21 (Knopf, $28). “I was born in the midst of revolution,” writes the author, winner of the 2018 Pulitzer Prize for commentary. “The son of a preacher, the grandson of a preacher. The great-grandson of preachers, too”—all Methodists. He was born in Alabaster, Alabama, outside Birmingham, on April 5, 1963—11 days before the scathing “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “I have been gravely disappointed with the white moderate…who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice.” Among those were “the white ministers, priests and rabbis of the South” who have “remained silent behind the anesthetizing security of stained glass windows.” In this memoir, Archibald, a columnist for The Birmingham News, fiercely comes to terms with how he grew up—including his preacher-father’s failure “to use his own pulpit for justice.” More’s the loss that in this year, neither Archibald, a Nieman Fellow, nor students were in residence, when he could have contributed so much to so many vital campus conversations.

Statelessness: A Modern History, by Mira L. Siegelberg, Ph.D. ’14 (Harvard, $35). A University Lecturer in the history of international political thought at Cambridge (U.K.) addresses one such fundamental idea: the plight of those left stateless (created by the millions in the aftermath of the two world wars) and the state-based order that prevails today—with more than 12 million stateless people, and millions of refugees and asylum-seekers. Siegelberg observes that although we overlook boat people and others, a pandemic may be clarifying, as it demonstrates “the undeniable importance of national governments assuming responsibility for collective catastrophes.”

Neither Settler Nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities, by Mahmood Mamdani, Ph.D. ’74 (Harvard, $29.95). Columbia’s Lehman professor of government and professor of anthropology examines citizenship in another way: as the intersection of the nation-state with the colonial state, usually resulting in the empowerment of a religious or ethnic majority at the expense of a minority (beginning in the New World, and applied in Sudan, South Africa, Israel, and elsewhere). The way out of cycles of violence and repression, he argues, is separating efforts at political community-building from past projects of colonialization.

Dream Big! How to Reach for Your Stars, by Abigail Harrison (Philomel, $12.99 paper). Chipper advice from “Astronaut Abby,” a Wellesley graduate and Harvard Medical School lab research assistant , who aims to be an astronaut and is a self-appointed ambassador for science and STEM education. Her advice focuses on knowing what your dream is, researching it, forming a plan to pursue it, and standing up for it. She writes for young readers—but after 2020, we could all use a little bucking up.

Stuck: Why Asian Americans Don’t Reach the Top of the Corporate Ladder, by Margaret M. Chin ’84 (New York University Press, $28). Chin, professor of sociology at Hunter College and the Graduate Center of CUNY (an advocate for diversity at Harvard and elsewhere), examines how the so-called “model minority” of high-achieving high-school and college students hits a “bamboo ceiling” in the workplace. Her research suggests ways that trust can overcome the tropes (from wartime enemies to tiger moms).

The Black Church: This Is Our Story, This Is Our Song, by Henry Louis Gates Jr., Fletcher University Professor (Penguin, $30). The latest book-cum-PBS project by Gates explores the institution that provided “a liminal space brimming with subversive features” as “Black people collectively awaited freedom.” He begins before the beginning (“In the Africa of our ancestors, the gods had a thousand faces and a thousand names”) and ends with his own boyhood experiences in the church.

Nuclear Folly: A History of the Cuban Missile Crisis, by Serhii Plokhii, Hrushevs’kyi professor of Ukrainian history (W.W. Norton, $35). As was the case with the author’s history of the Chernobyl nuclear disaster, this is hardly the first account of the near-catastrophic U.S.-U.S.S.R. confrontation. But again, drawing on KGB documents, Soviet memoirs, and more, Plokhii broadens and internationalizes the narrative—usefully so at a time of heightened tensions, lapsing nuclear treaties, and shifts in the world order. He writes grippingly.

Broke: Patients Talk about Money with Their Doctor, by Michael Stein ’81 (University of North Carolina Press, $19 paper). Stein, a physician who practices in a poor neighborhood and a professor of health law, policy, and management at Boston University, writes that “with the country seemingly getting richer, my patients find themselves getting poorer”—unable to afford prescriptions, copays, and more. He dignifies their struggles, and illuminates how far the country is from equitable care, by sharing their voices. “I’m so broke I have to rinse off paper plates,” says the first, and there are many, heartbreaking others.

The Toughest Kid We Knew, by Frank Bergon, Ph.D. ’73 (University of Nevada Press, $24.95). Further explorations of the changing West, by a chronicler of the San Joaquin Valley. “The New Old West: A Personal History,” the subtitle, gets at modern agriculture and the traditional ethos of ranching, presenting both its good qualities (valorized by television and city slickers) and its harsher realities. The “Captured!” at Steptoe Hospital, Ely, Nevada, birth announcement—“HAIR: brown (what there is of it)”—from 1943, reproduced here, is a hoot (“drinks Holstein cocktails”).

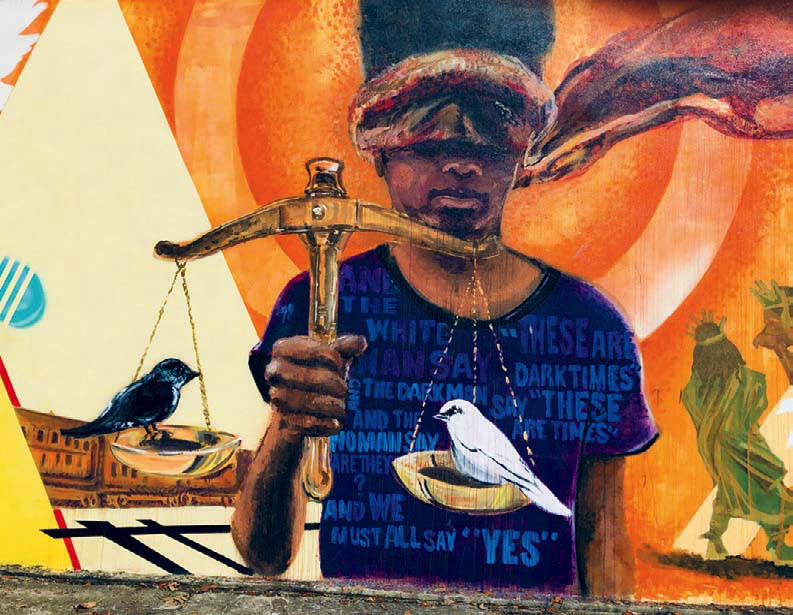

The mural These Are Times, by Ayo Scott, in Plessy Park, New Orleans

Photograph by Amy Nathan

Together, by Amy Nathan ’67, M.A.T. ’68 (Paul Dry Books, $14.95 paper). Through the stories of Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson, both born in New Orleans in 1957, Nathan relates the American arc of segregation, civil rights, and movement toward some new basis for race relations—tracing back to their families’ intersection in 1892 in Plessy vs. Ferguson, which laid the foundation for the Supreme Court’s decision validating “separate-but-equal” facilities.

Ask the Experts: How Ford, Rockefeller, and the NEA Changed American Music, by Michael Sy Uy, Ph.D. ’17 (Oxford, $74). Uy, resident dean of Dunster House and lecturer in music, examines the intersection of philanthropy, cultural policy, and the arts. He examines how two foundations and the National Endowment for the Arts invested $300 million in the field of music between the end of World War II and the Bicentennial, adopting what they deemed objective criteria and consulting experts (Leonard Bernstein ’39, D.Mus. ’67, Aaron Copland, D.Mus. ’61, et al.): a male, Western cohort who defined what passed for excellence, but can also be seen as an elite, connections-based way of parsing, and paying for, culture.

Rescuing the Planet: Protecting Half the Land to Heal the Earth, by Tony Hiss ’63 (Knopf, $28). An on-the-ground manifesto aiming to “stave off the mass extinction crisis by keeping life alive”—principally by protecting 50 percent of the planet in a natural state by 2050. Although the goal may seem outlandish, if worthy, one might take encouragement from remembering that the North American boreal forest, a lot of Amazonia, and some of Siberia are intact.

Utopian Ruins: A Memorial Museum of the Mao Era, by Jie Li, Loeb associate professor of the humanities (Duke University Press, $31.95 paper). A scholarly examination of the way in which memories of Mao’s China are created, preserved, and used. Though lay readers may find the analysis academic, the visual materials are powerful, and the persistence of Maoist influence on the culture and politics of the People’s Republic (and manipulation of that legacy for current ends) makes it important to know how and why. It was not so long ago that, as Li writes, “The utopian and catastrophic dimensions of the Mao era left behind trauma as well as nostalgia….”

How To Be Depressed, by George Scialabba ’69 (University of Pennsylvania, $27.50). The essayist and critic (profiled in “Radical Reviewing,” November-December 2013, page 20) is a lifelong sufferer from clinical depression. In this unusual memoir-essay, he helps to demystify the disease, and perhaps to humanize care, by presenting edited records of his treatment from 1969 through 2016.

The Code Breaker, by Walter Isaacson ’74 (Simon & Schuster, $35). The biographer of innovators and others (among them Leonardo da Vinci and Steve Jobs) enjoys spectacular timing with the release of this substantial new work, subtitled “Jennifer Doudna [Ph.D. ’89], Gene Editing, and the Future of the Human Race,” about the co-winner of the 2020 Nobel Prize in chemistry for her work on the CRISPR gene-editing technique. She was, Isaacson reports, hooked on her life’s fruitful work when she read James Watson’s The Double Helix as a sixth-grader, discovering Rosalind Franklin and the potential for women to be pioneering scientists.