The first hot-air balloon trip across the English Channel began buoyantly. “We rose slowly and majestically from the Cliff,” wrote John Jeffries, A.B. 1763. A “beautiful assembly” cheered on the Boston-born medical doctor and his more expert partner, French inventor and balloonist Jean-Pierre Blanchard (who had hoped to leave Jeffries behind, despite his funding of the expedition).

But floating technology in 1785 wasn’t what it is today. Fifty minutes into the January trip, the balloon began to descend and the two tossed off a couple sacks of ballast to lighten their load. Forty minutes later, the balloon sank again. “We immediately threw out all the little things we had with us,” Jeffries wrote. “Biscuits, apples, &c, and after that one of our oars or wings; but still descending, we cast away the other wing.” The situation grew more desperate. “Still approaching the sea,” he recalled, “we began to strip ourselves, and cast away our cloathing.” It’s a wonder his jaguar-pelt hat, featured in a contemporary portrait and now housed at Houghton Library, survived.

A portrait of Jeffries with barometer in hand

Courtesy of the Houghton Library

As their coats and trousers fell, their balloon rose. Above the French cliffs they flew, soaring higher than at any other point on the journey, Jeffries recalled in “A Narrative of the Two Aerial Voyages of Doctor Jeffries with Mons. Blanchard,” two signed manuscripts of which are also in Houghton. The only remaining step was to land, but they were speeding toward a forest too extensive to traverse. Needing both to rise above thick tree trunks and halt momentum, it “instantly occurred” to Jeffries that they could supply something to accomplish these goals “from within ourselves.” “We had drank much at breakfast,” he explained. With no restroom on board, and the frigid air stifling perspiration for hours, they managed to fill two external bladders with, “I verily believe, between five and six pounds of urine.” As they cast the bladders away, the balloon rose, allowing him to grasp a tall tree’s topmost branches and slow their pace. “[H]owever trivial or ludicrous it may seem,” Jeffries wrote, emphasis his own, “I have reason to believe [it] was of real utility to us, in our then situation.”

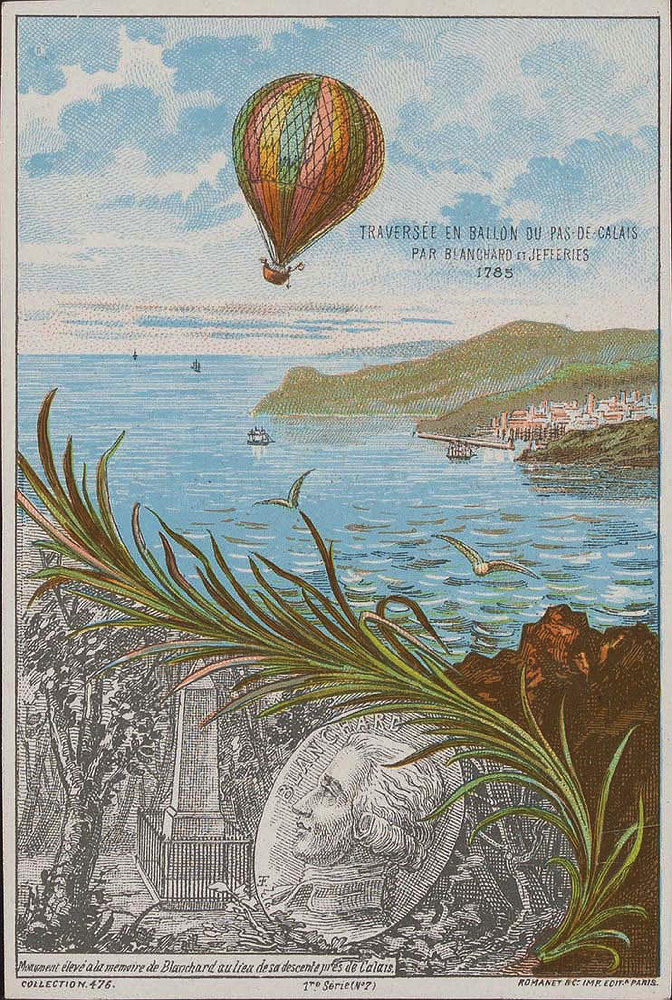

Jeffries and Blanchard fly across the English Channel.

Courtesy of the Houghton Library

The balloon landed safely. Within minutes, French citizens made their way to the aircraft, providing “every kind of civility and assistance” to Jeffries and Blanchard—including clothes for them to wear.

Much of the expedition’s non-jettisoned paraphernalia sits in Houghton, donated by Jackson professor of clinical medicine James Howard Means, A.B. 1907, M.D. ’11, husband of Jeffries’s granddaughter, Miriam. When the library reopens, the collection will be displayed in its renovated lobby. But alongside calling cards, an almanac, and a French-English pocket dictionary, there will be no life jackets. Those, notes curator John Overholt, were tossed overboard, too.