Imaginary Peaks, by Katie Ives ’99 (Mountaineers Books, $26.95). Riffing on the infamous Riesenstein Hoax (about an unscaleable, indeed imaginary, set of peaks in British Columbia), and drawing on her concentration in literature and her M.F.A., the author probes what mountains mean in the human imagination. Roaming widely through the literary topography of exploration, Ives, editor in chief of Alpinist magazine (“dedicated to the art of ascent in its most powerful manifestations”), takes the armchair climber far indeed. She is, herself, comfortable with the real deal: her biography says she “enjoys moonlit ice climbs and long granite ridges.”

Say It Loud! On Race, Law, History, and Culture, by Randall Kennedy, Klein professor of law (Pantheon, $30). Essays by (in his words) “a Black/Negro/Colored/African American law professor…born in Columbia, South Carolina…four months after…Brown v. Board of Education.” Kennedy, profiled in “Black, White, and Many Shades of Gray” (May-June 2013, page 25), begins with three beliefs: that “racism continues to be a major force in America,” “there is much to be inspired by when surveying the African American journey from slavery to freedom,” and “social relations are complex and messy.” He’s masterful at addressing all three—and their intersections.

Money Magic: An Economist’s Secrets to More Money, Less Risk, and a Better Life, by Laurence Kotlikoff, Ph.D. ’77 (Little, Brown, $29). Boston University’s Fairfield professor, creator of the MaxiFi Planner program, tries to help you cope with an intractable challenge: “[T]he financial problems we face are unbelivably complex.” In the new year, his chatty guide (“Find a career you love and others hate”) might help you, or the youngsters you advise, get it right. Rule eight of his 50 top secrets: “Marry for money. You’re worth it.”

Cogs and Monsters: What Economics Is, and What It Should Be, by Diane Coyle, Ph.D. ’85 (Princeton, $24.95). The Bennett professor of public policy at the University of Cambridge critiques her discipline from within. The classical economics of self-interested individuals fits reality poorly, all the more so in a era of digital technology, the Web, and artificial intelligence, where socially influenced unknown factors and influences, with their scale and network effects, increasingly prevail. Her reasoning is intellectual, not ideological: “Economics needs both theory and evidence about what actions, by governments or others, will lead to better outcomes when both governments and markets are bound to fail.”

Whither College Sports, by Andrew Zimbalist, Ph.D. ’74 (Rutgers, $39.95 paper). The Woods professor of economics at Smith College deliberately takes the fun out of sports: he is the leading academic analyst of the sector. But as “Amateurism, athlete safety, and academic integrity,” the subtitle of these collected essays, suggests, at the big-time level, the fun is already chimerical, what with the billions of dollars at stake overriding student athletes’ health and academic wellbeing, recruiting scandals, and more. Useful to have. Zimbalist threw cold water on a Boston Olympics in these pages (“A Fiscal Faustian Bargain,” July-August 2015, page 39).

The Survival Nexus: Science, Technology, and World Affairs, by Charles Weiss ’59, Ph.D. ’65 (Oxford, $39.95). A Georgetown professor emeritus steeped in science and technology policy, Weiss delivers a serious guide to the connections between the world’s problems and the conduct of global politics: climate change, nuclear weapons, global health and pandemics, etc. Not light reading, but then again, the subjects deserve, and receive, intelligent treatment.

Coming to grips with many of those problems won’t be a snap of the fingers, insofar as private enterprises are significant actors, as Ari Ezra Waldman ’02, J.D. ’05, professor of law and computer science at Northeastern, makes clear in Industry Unbound (Cambridge, $24.95). Tech companies’ incentives undercut consumer privacy to extract and market valuable data—and erode trust in the process. A somewhat lighter, big-picture approach is taken—as one might guess from the authorship—in The Age of AI and Our Human Future (Little, Brown, $30), by Henry A. Kissinger ‘50, Ph.D. ‘54, Eric Schmidt (Google), and Daniel Huttenlocher (MIT’s dean of computing). Although they “differ in the extent to which we are optimistic about AI” as it changes “human thought, knowledge, perception, and reality,” they do also touch upon worries like “AI-enabled war.”

Given the above weighty worries, perhaps it’s good to have Smarter Tomorrow, by Elizabeth R. Ricker, Ed.M. ’16 (Little, Brown, $28), who speaks about “cognitive enhancement.” The subtitle suggests that “15 minutes of neurohacking a day” can bring about better work, faster thinking, and all around productivity. The cookbook-like approach is in approachable bite-sized bits, but the recipes could be more appetizingly titled than, say, “Neurohacking with Placebos: The Growth Mindset as Intervention.” In a similar vein, with similarly social-media/TED Talk-friendly titling, is Find Your Unicorn Space: Reclaim your Creative Life in a Too-Busy World, by Eve Rodsky, J.D. ’02 (Putnam’s, $27). A serial adviser—wealthy families and philanthropy; how to redistribute domestic work so women get a fairer deal—now turns to how you can “give yourself permission to reclaim, discover, and nurture the natural gifts and interests that make you you.” This may lead to essential liberation or, of course, intensification of an already insufferably self-absorbed era: TBD.

Seven Games, by Oliver Roeder, NF ’20 ((W. W. Norton, $26.95). A former Nieman Fellow and writer for FiveThirtyEight, Roeder, now editor of The Riddler, a game theorist, here he turns to other kinds of games. He produces an engaging group biography of checkers, chess, Go, backgammon, poker, Scrabble, and bridge, and those who master them or merely strive to. “Games generate excitement, obsession, competition, and deep thought”—as here, where philosophy, psychology, and art are seamlessly invoked. Good fun and food for thought, well presented.

The Last Letter: A Father’s Struggle, a Daughter’s Quest, and the Long Shadow of the Holocaust, by Karen Baum Gordon ’78 (University of Tennessee, $24.95 paper). In Dallas, at age 86, Gordon’s father attempted suicide. Karen, seeking to understand, delves into her grandparents’ lives (lost in the Holocaust), her father’s inability to save them, and the family’s story as revealed in letters from 1936 to 1941. An intimate window into the psychological cost individuals and families paid as a result of one of humanity’s greatest inhumanities—“big history as seen through ordinary lives,” as the author appropriately characterizes it.

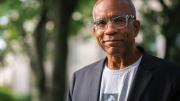

A new poetry collection from the prolific, multitasking Kevin Young

Photograph by Melanie Dunea

Stones, by Kevin Young ’92 (Knopf, $27). New poems by the prolific, polymathic director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture. He writes, in three-line chunks, on all manner of things, from the serious to memories of bathing with cousins (“That was back when dirt/& each other/was all we loved...”). Young spoke movingly about his Harvard years last June (harvardmag.com/comm-haa-meeting-21), and his foundational anthology of African American poetry was reviewed in the September-October 2021 issue (“Critique and Joy,” page 58).

Power and Liberty: Constitutionalism in the American Revolution, by Gordon S. Wood, Ph.D. ’64 (Oxford, $24.95). At a time when the value and role of the Constitution appear in danger of being actively ignored (when not forgotten), it is invaluable to have Wood, Way University Professor emeritus at Brown and the preeminent historian of the era, to explain anew why the “founding documents and the principles expressed in them have become our source of identity”—and had better well remain so. A lucid, succinct, readily accessible treatment of the essential American ideas.