After wars end, they live on—in history, memory, culture, and societies’ subsequent choices. In a searching analysis, Elizabeth D. Samet ’91, professor of English at the United States Military Academy (profiled at harvardmag.com/alumna-west-point-16), has examined the literature and art that followed World War II, resulting in Looking for the Good War: American Amnesia and the Violent Pursuit of Happiness (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $28). She peels back sentimentality about U.S. exceptionalism, and its effects on contemporary attitudes toward violence and the military—and the country’s many wars since, including in Afghanistan. “In the midst of a miserable peace,” she writes, “the pains of war are quickly forgotten while its imagined glories grow. Causes are retrofitted, participants fondly recall heroic gestures.” And not only recently: Samet involves the Civil War, “misremembered for a century and a half.” She begins with an example of resistance and persuasion that belies gauzy memories of a people united as one in the 1940s:

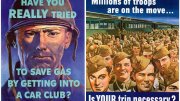

During World War II, American automobile owners were required to affix gas-rationing stickers to their windshields. Drivers were classified by occupation…each authorized a certain number of gallons per week. The backs of many of these stickers posed a pointed question to the man or woman at the wheel: “Is This Trip Really Necessary?” Designed to train civilian attention on an unseen war being fought far away, the sticker became at once a badge of sacrifice and a practical necessity. It would soon become a valuable black-market commodity.…That the public should need reminding; that there was in fact a robust black market (chiefly in beef and gasoline), operated, as John Steinbeck noted…, not by “little crooks, but by the best people”; that the government felt the need to launch an unprecedented propaganda campaign to motivate civilians and soliders alike—all these facts suggest the degree to which the goodness, idealism, and unanimity we today reflexively associate with [the war] were not as readily apparent to Americans at the time.

John H. Abbott was a conscientious objector assigned by the authorities to a series of stateside public works details until he refused even this duty. Convicted in 1943…he served two years in a federal prision. Years after the war…Abbott recalled a prank he and some of his fellow C.O.s used to play: “Those gasoline stickers for rationing that you had on your windshield….We’d scratch out ‘trip’ and write ‘war’: Is this war really necessary?” One can disagree with Abbott—in other words, one can, as I do, believe that the United States’s involvement in the war was necessary—yet still question the way that participation has been remembered in the wake of wars considerably less galvanizing and unifying. Has the prevailing memory of the “Good War,” shaped as it has been by nostalgia, sentimentality, and jingoism, done more harm than good to Americans’ sense of themselves and their country’s place in the world? Has the meaning of American force been perverted by a strident, self-congratulatory insistence that a war extraordinary in certain aspects was, in fact, unique in all? Has the paradoxical desire to divorce that war from history—to interpret victory as proof of America’s exceptionalism—blinded us to our own tragic contingency?