Before Netflix-watchers debated whether Carole Baskin fed her husband to tigers in the docuseries Tiger King, before Serial podcast sleuths investigated the murder of Hae Min Lee, and before the televised O.J. Simpson murder trial forever changed the way Americans thought of ill-fitting gloves—all the nation could talk about was Helen Jewett and her burning mattress.

In April 1836, Jewett—a 23-year-old prostitute in New York City—was found axed in bed, her mattress lit on fire. The prime suspect? “Upstanding” 19-year-old shop clerk and Jewett’s secret lover, Richard P. Robinson. According to one contemporary pamphlet, the case was “the subject of moral elucidation and horror in every family, in the taverns, on the side-walks, and at the wharves” across the nation, long before televisions or even telephones. This “most horrid tragedy that ever froze the blood” was one of America’s first true-crime obsessions, setting the stage for crime media as we know it.

Since about the eighteenth century, cases like Jewett’s had been reported in penny papers and crime pamphlets (long sensationalized narratives)—more than 420 of which are housed in the Harvard Law School Library’s Studies in Scarlet collection. Six-cent papers like the New York Times and the Evening Post frowned upon crime reporting and stuck to financial and political coverage instead. But the Jewett case was a whole other beast.

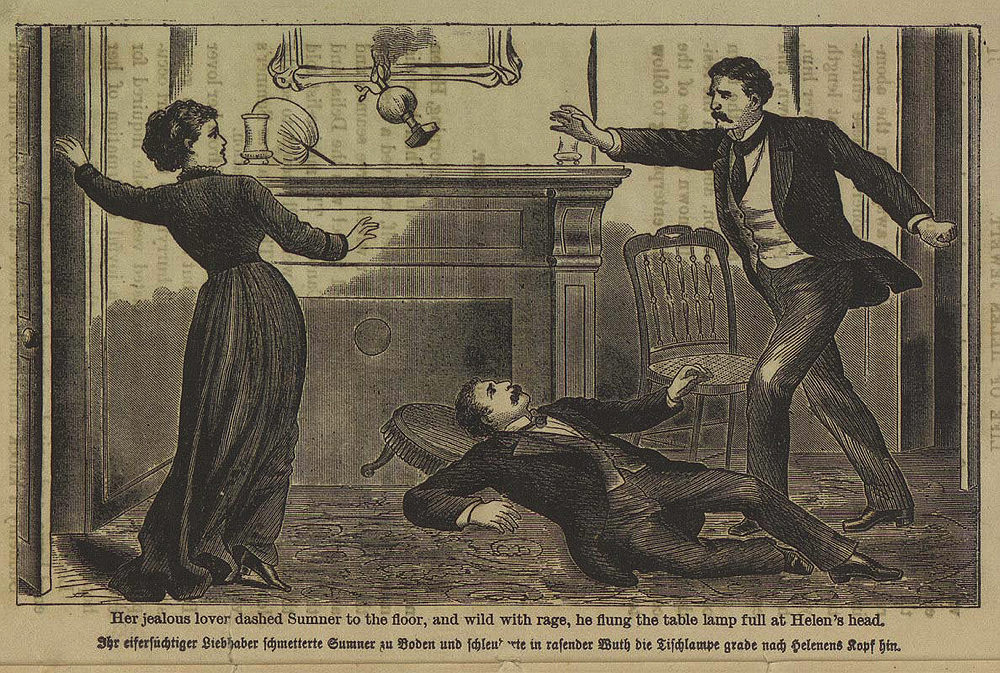

Pamphlets emphasized the violence in Jewett’s past relationships.

Image courtesy of Harvard Law School Library

The crowd at Robinson’s trial was a verifiable “deluge,” swelling against the walls and forcing some spectators to hang onto window moldings to stay afloat. Now, major papers had to report the trial to stay relevant, and they reluctantly competed with the penny papers’ Jewett scoops. Some publications like the Evening Post even apologized to readers for reporting such a “disgusting” and “disagreeable” case, claiming “public excitement” had made it necessary. As one pamphlet put it, the nation was united in an “inherent, morbid love of the horrible.” And now, they had the media to support it. True crime had gone mainstream.

When Robinson was acquitted in June 1836, the public and even the papers, “usually so servile to the expressed opinion of twelve numbskulls,” voiced their outrage. Yet in all this talk, there was very little about the victim. Newspapers inserted Jewett’s biography, Mad-Libs style, into the template of: “gentle-mannered girl,” kicked out of a good home, falls into vice. Besides popularizing it, perhaps the Jewett case set a precedent for true crime—that often it commemorates victims less for the lives they lived, and more for the way they ended.