Community cookbooks are not known for remarkable scope and ambition. As delicious as a favorite pasta salad might be, it tastes about the same whether made in Arkansas, Nevada, or Maine, jokes Marylène Altieri, Schlesinger Library curator of books and printed materials. A recipe for soured seal liver is different.

“Place liver in enamel pot or dish and cover with blubber,” wrote Shishmaref Day School student Agnes Kiyutelluk. “Put in warm place for a few days until sour.” Her simple instructions are followed by a direct appraisal of the outcome. “Most of the boys and girls don’t like it, except the grown-ups and old people,” she concluded. “I don’t like it either.”

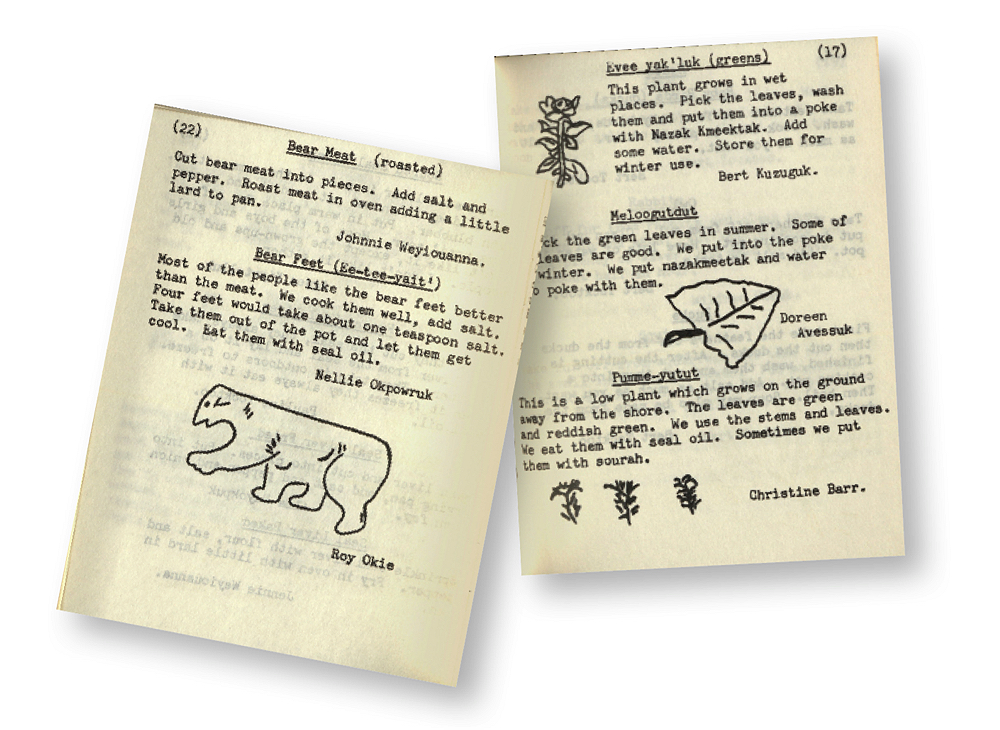

The recipe is one of several evocative and straightforward selections in the Eskimo Cook Book, a hand-illustrated miniature booklet prepared by students of the school, in Shishmaref, Alaska—a fishing-dependent Inupiat island village just north of the Bering Strait. The 1952 text, published as a fundraiser for the Alaska Crippled Children’s Association, is a densely packed prize of the library’s collection of historic cookbooks.

In her introduction, Shishmaref teacher Isabelle B. Bingham recalled suggesting to her students that they write down their families’ favorite recipes. “Eskimo don’t have cook books!” a student responded. Bingham, born in New York state, said that white people didn’t always have cookbooks either. With some coaxing, her students filled a 36-page booklet. It was a success, with multiple editions published in the following decades.

Bingham’s students didn’t waste words. To make roasted bear, “Cut bear into pieces,” wrote Johnnie Weyiouanna. “Add salt and pepper. Roast meat in oven adding a little lard to pan.” In the next bear-centric recipe, Nellie Okpowruk stated that “most of the people like the bear feet better than the meat” and recommended boiling them and serving with seal oil. Some instructions, like the steps for storing salmon berries, would be impossible to follow without the hand-drawn sketches.

The cookbook doubles as an inadvertent guide to the area’s natural environment and wildlife. Students described when and where to find seasonal greens like asak-luk (Arenaria peploides) and ah-lowe-kuk (Rumex arcticus) and how to prepare them. A fermented walrus recipe from the 1989 edition directs readers to bury a two-foot-by-two-foot slab of its meat deep in the island’s permafrost during the spring to dig it up in the fall.

Unfortunately, as the environment changes, these recipes are becoming outdated. Much of Shishmaref’s permafrost has thawed. Sea ice that protects its coast from erosion is melting earlier in the spring and freezing later in the fall. In 2016, Shishmaref residents, responding to sinkholes and a receding coastline, voted to relocate to a location on the mainland—a project estimated to cost $200 million. One of the few published materials from the island, the cookbook now serves both as a preservation of culture and a memento to what was.