From the cliffs over the Jucar River, in the midst of an old Castilian city, a group of medieval houses makes up the Museum of Abstract Art of Cuenca. Medieval from the outside, radically modern in the inside, it is “the most beautiful small museum in the world,” in the words of Alfred Barr Jr. It was the first contemporary art museum ever built in Spain and displays the extraordinary collection of abstract painter Fernando Zóbel-Montojo. Both a museum and an island of avant-garde culture, Casas Colgadas (“hanging houses”) opened in 1966 and brought a breath of fresh air to Spain in the last years of General Francisco Franco’s regime.

The museum is only the best known of several cultural enterprises that Fernando Zóbel ’49 created during an intense life devoted to the practice of painting, the study of art history, and collecting (the largest collection of Spanish drawings at the Harvard Art Museums is the result of his generosity). Others include another contemporary art museum, the Ateneo Museum (Manila), but also books, articles, lectures and, most importantly, an intense and prolific career as a painter, draftsman, and printer. A life devoted to art, in all its multifaceted aspects.

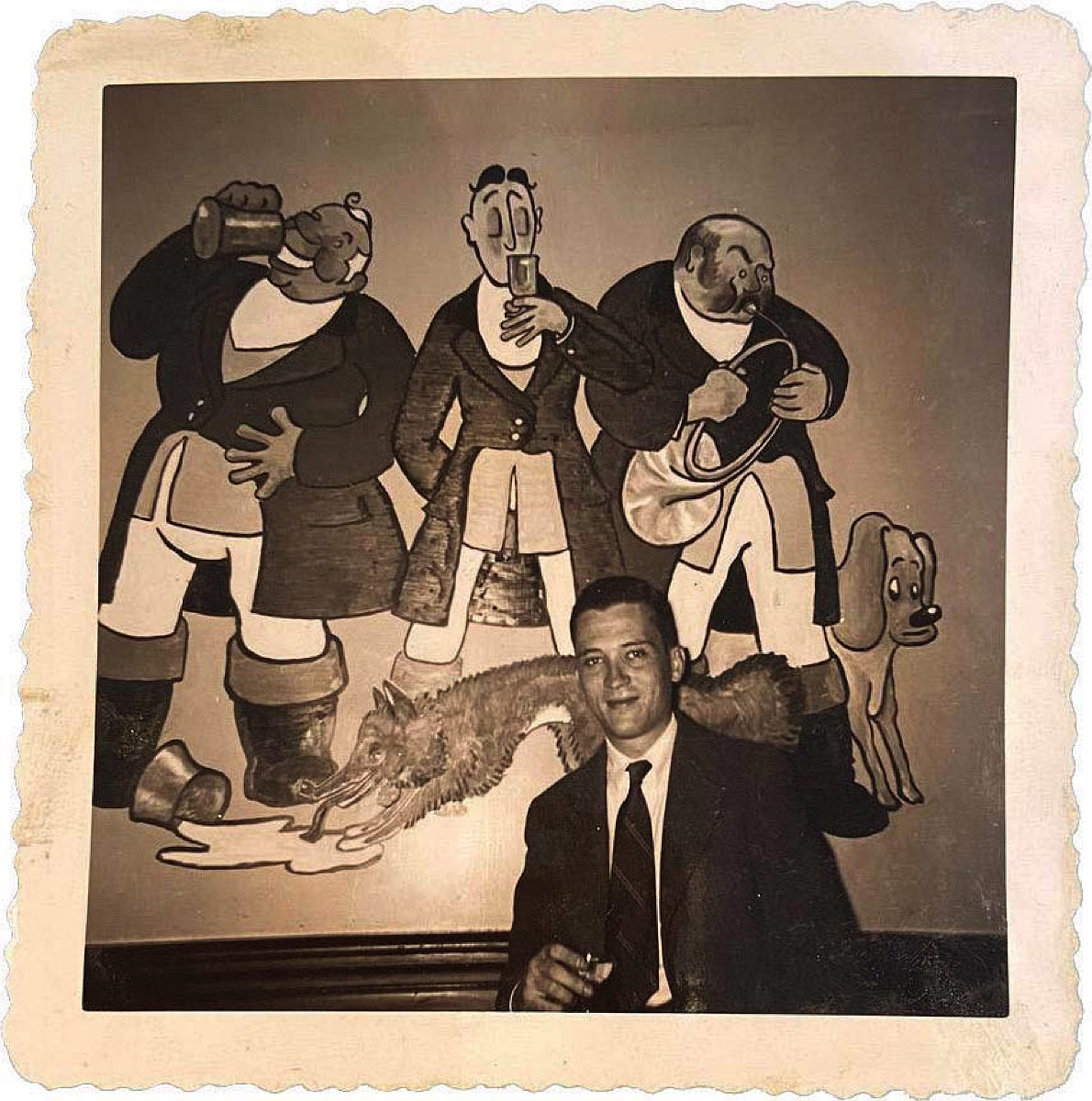

Youthful caricatures painted at the Fox Club

Image courtesy of Felipe Pereda

Born in Manila in a family of Spanish origin (his father was president of the Ayala Corporation), Fernando Zóbel enrolled at Harvard in 1946. He left behind a city reduced to ashes as a result of the Japanese resistance and the American bombardments of World War II. At the College, Zóbel immersed himself in the study of comparative literature, particularly under leading critic and Babbitt professor of comparative literature Harry Levin, for whom Zóbel would write one of the earliest English translations of the play Don Perlimplín in Love (1946) by Federico García Lorca. More important for his future as an artist was of course Zóbel’s discovery of painting: old and modern, the study of its history, but also of its making. While his notebook’s drawings, preserved at the Houghton Library, keep the memory of the classes he took in art history, those he published in the Harvard Alumni Bulletin (1948-1952) reveal his enthusiasm for Walter Gropius’s introduction of modern art to Cambridge.

As a painter, Zóbel would one day become an important figure of the Spanish avant-garde, but he started as a caricaturist (as the murals he painted at the Fox Club testify). It was his exposure to modern art at the exhibitions of the masters of the Bauhaus at the Germanic Museum (today Busch-Reisinger), and to American paintings in Boston and later in New York, that led Zóbel to modernity. The encounter with the work of Mark Rothko before meeting him in person finally marked his conversion to abstraction.

Zóbel would first present his “big oil drawings” at the Guggenheim Museum in New York at a now iconic show, Before Picasso; After Miró (1960)—paintings that pursued the ambitions of the American abstract expressionists with a technique indebted to his study of Asian calligraphy and a style that blurred the distinction between painting and drawing. His transnational style speaks of his cosmopolitanism, his breaking through geographical borders. His scholarly training, on the other hand, pushed his interests beyond another frontier limiting the modern artist: the line dividing past and present.

Back in 1954, Zóbel had converted into a “modern” painter in Manila, but as he grew older, he would never give up his strong sense of history, even of tradition, a unique admiration for the history of painting that unveiled traces of modernity hidden in the work of the old masters. Zóbel was convinced that to learn how to paint, the artist needs to learn first how to “look”: “Drawing is my way of seeing,” he once wrote. Many of his paintings are a result of such an exercise in “seeing.” “Dialogues with the old masters,” he called them: a radical anachronistic move that renders his painting unique if not exceptional.

A watercolor of Harvard, from memory, 1975

Image courtesy of Felipe Pereda

Such an interest had first grown in Cambridge, as an intern at the Houghton Library under the mentorship of Philip Hofer––the curator of drawings––with whom Zóbel discovered the art of close looking. Zóbel would build a friendship with Hofer lasting the next 30 years (their correspondence is kept at the library). His letters to Hofer testify to the love and gratitude attached to his student years. The following comes in one of them, sent from Madrid, in December 1975, and introduced by a simple but beautiful watercolor:

“Above is a bit of Harvard from memory. I mean, really from memory. No photos. I’d like it to be a kind of exercise in what’s left visually. Probably much looser than the above—and larger, of course, but not big. The thing up there is a bit of Charles in Autumn. Anything like? Not cartoon like Cuenca, but an exercise in line + color + memory. A kind of Arcadia I suppose, but the Harvard memories are pretty idyllic in retrospect, ‘scenes we remember as unchanging, because there we changed,’ as Auden more or less put it.”

Felipe Pereda, the Fernando Zóbel de Ayala professor of Spanish art, curated the exhibition, Zóbel. The Future of the Past, Museo del Prado, Madrid, on display through March 5, and is co-author, with Christopher Maurer and Luis Fernández Cifuentes, of Zóbel Reads Lorca.