In the spring of 1874, 23-year-old Archibald “Archie” Henry Grimke graduated from Harvard Law School (HLS). Eventually, as a respected Boston attorney, founder of the NAACP, and president of the Association’s Washington, D.C., branch, Archie would serve as American consul to the Dominican Republic under President Grover Cleveland. Archie’s graduation from HLS had ensured his place atop fin de siècle America’s “talented tenth”—those whom his friend and fellow alumnus W.E.B. Du Bois, A.B. 1890, Ph.D. ’95, tasked with “guid[ing] the Mass away from the contamination and death of the Worst.” Though Archie was not the school’s first Black graduate—that honor went to his friend, the Virginia native and Massachusetts legislator George Lewis Ruffin (1834-1886)—Archie’s matriculation at the country’s oldest law school had been notable given the reputation surrounding his famous last name.

For Archie’s southern classmates, “Grimke” was synonymous with a recently delegitimized slaveholding elite whose political and economic power had only been dead for nine years. No doubt many of them knew the colonial exploits of John Faucheraud Grimke (1752-1819), Archie’s paternal grandfather and an eighteenth-century justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. As one of the wealthiest slaveholders in the Carolina low country, Judge Grimke was respected among his fellow plantocrats for his contributions to the South Carolina constitution, and for his 14 children, including two sons—Archie’s uncles Thomas Smith and Frederick Grimke—who became respected jurists in their own right. Considerations Upon the Nature and Tendency of Free Institutions (1846), Frederick’s 544-page examination of America’s two-party political system, was a standard text for Harvard undergraduates well into the twentieth century, while Thomas’s writings during the South Carolina nullification crisis of the 1830s were canonical texts of states’ rights conservatism.

Images courtesy of the Library of Congress

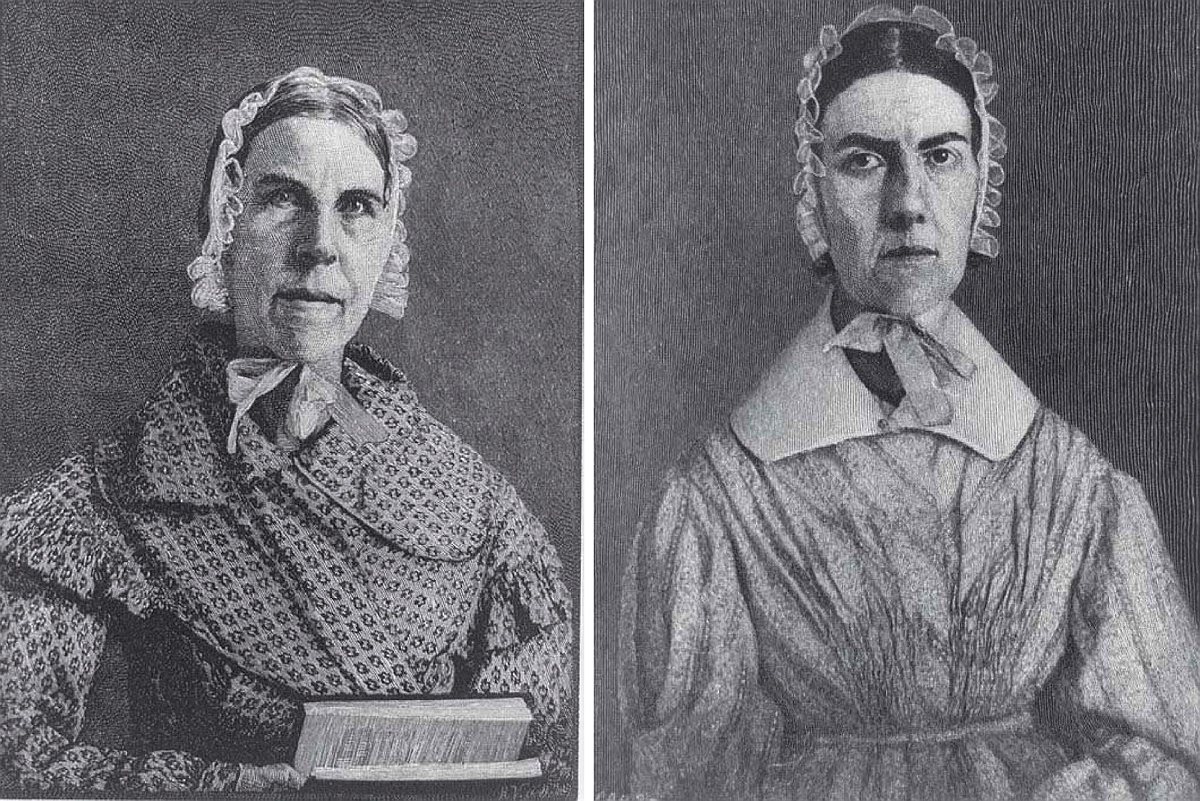

Although Archie’s southern classmates knew the Grimke name in connection with the former Confederacy, his northern classmates more likely associated it with two of antebellum America’s most infamous abolitionists. Sarah Moore Grimke and Angelina Grimke Weld—Judge Grimke’s daughters; sisters to Frederick and Thomas—had forsaken their birthright (or so legend had it) to become Philadelphia abolitionists who demanded that southern white women like themselves “cast their lot” with the oppressed and “raise [their] voices” in the public sphere. In 1838, nearly 40 years before Archie’s law school graduation, Angelina made history as the first American-born woman to address a state governing body when she spoke before the Massachusetts legislature on anti-slavery and women’s rights. She then spent the decades before the Civil War with Sarah in Raritan Bay, New Jersey, administering progressive, integrated education for the offspring of some of the era’s most famous reformers.

Yet, for Archibald Grimke, the family name inflicted a lifelong burden that could not be reduced to the Old South mythology of his paternal ancestors or the self-righteous reform of his infamous aunts.

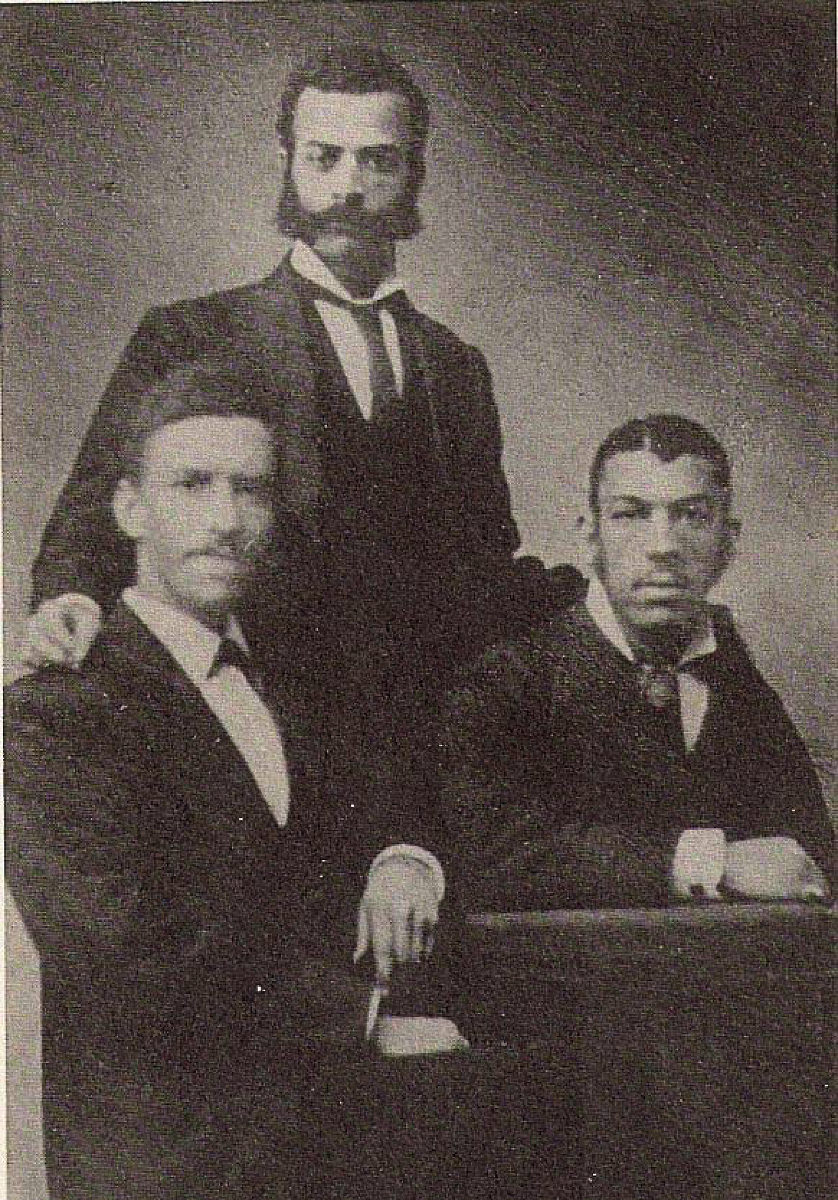

Nancy Weston, mother, c. 1885 (top); and the Grimke brothers—from left, Frank, Archie, and John, c. 1875

Images courtesy of the Moorland Spingarn Research Center, Howard University (top) and the Schomburg Library, New York Public Library

Although his Black mother, Nancy Weston (c. 1815-1895), always maintained that Archie and his brothers descended from “the greatest blood of the South,” the facts were less romantic. Henry F. Grimke, slaveholding brother of the anti-slavery Grimke sisters, had kept Nancy and their three sons enslaved, willing them to his white son, Montague (Archie’s older half-brother) and ensuring that Archie spent the Civil War beaten, starved, and tortured when he refused to “play the part of the slave.” Archie’s escape from the violence of postbellum Charleston was not due to the benevolence of his white aunts, but to the ingenuity of his abused and exploited Black mother, who pleaded with local missionaries to take her boys north to be educated. Angelina and Sarah Grimke only “rescued” their nephews when they read about their academic accomplishments in a local anti-slavery newspaper in 1868, and the anti-slavery orators still insisted that Henry Grimke had been a “kind master” and that “hard work and moral development” could save their Black nephews from “the adverse effects of their southern upbringing.”

Archie eventually defied the racial limitations of his era by ascending the heights of national law and politics, but this ascension occurred in the midst of continued racial violence, rising segregation, widespread disenfranchisement, and the continued economic exploitation of the Black masses. Like his famous white aunts, Archie managed to effect symbolic, if not substantive, change to the inequitable system in which he lived. And yet, just like his aunts, who often failed to reconcile their idea of “negro as cause” to the reality of “negro as man,” Archibald Grimke spent a lifetime wrestling with the consequences of the slave past to which he was born.