In his curatorial debut at the Harvard Art Museums, Horace D. Ballard moves the dial back on the origins of American art. The 26 paintings in “From the Andes to the Caribbean: American Art from the Spanish Empire” (through July 30) focus not on influences of early Jamestown or the arrival of Puritans at Plymouth Rock but on foundational shifts dating to 1493. That’s when a papal bull enabled Catholic sovereigns Isabella I and Ferdinand II to “not just map but claim all territories in the American hemisphere not already claimed by Christian monarchs,” says Ballard, Stebbins associate curator of American art since 2021. The decree further ordered “that any native and Indigenous persons and Africans brought over as slaves should be converted to Christianity.”

The gilt-framed iconography and portraits, on loan from the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation, explore three themes: entwined political and spiritual content, the role of empire-building in cultural identities, and links between labor and wealth. “This recentering amplifies histories,” he explains, “that still contour and shape the lived experiences of so many BIPOC [black, Indigenous, and people of color] individuals.”

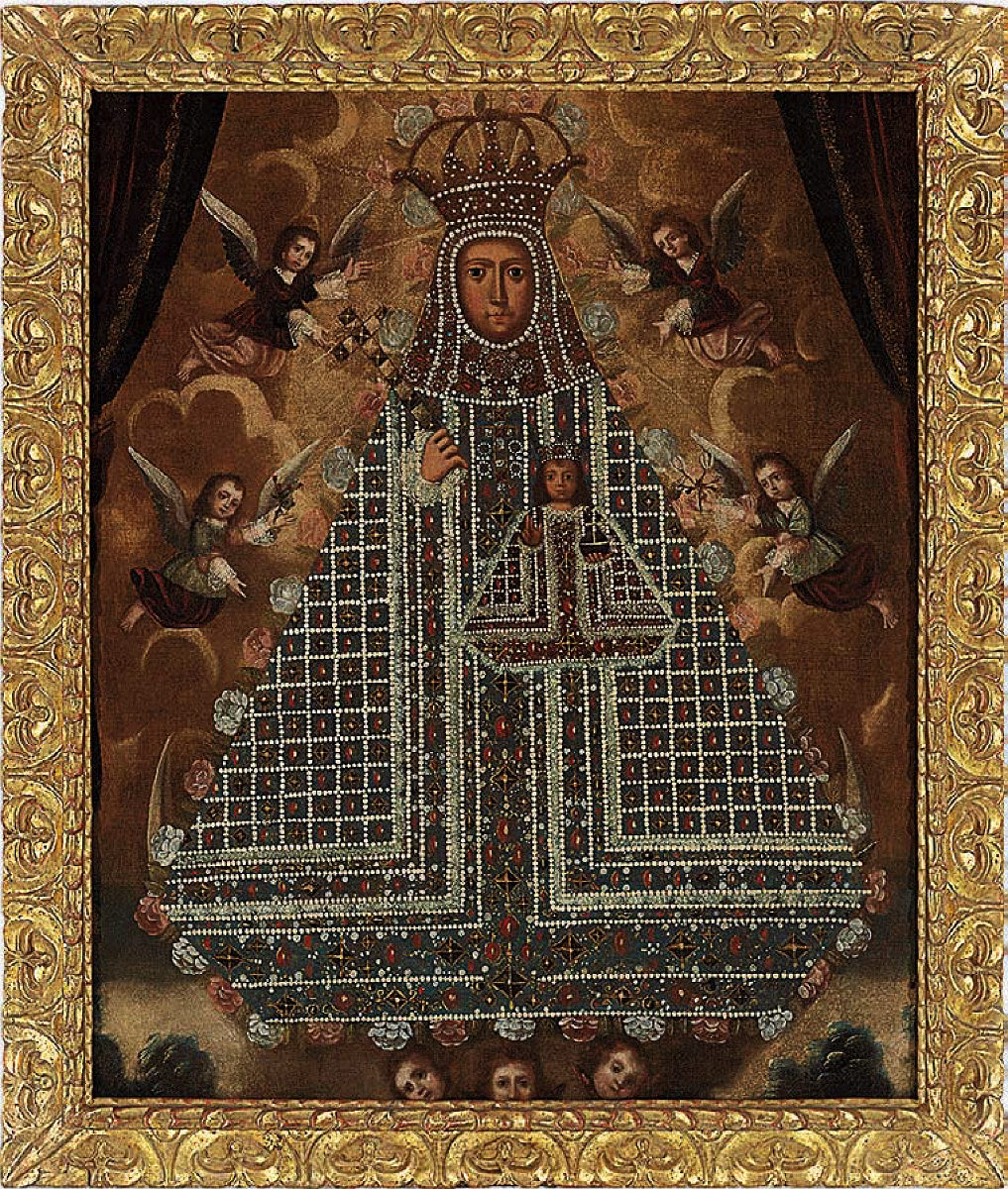

Our Lady of Guadalupe at Extremadura (1730-80)

Image courtesy of the Carl & Marilynn Thoma Foundation/ photographs by Jamie Stukenberg

Depictions of people of varying skin tones and other physical attributes suggesting syncretic identities reveal that “as Catholicism spread across the Americas,” Ballard adds, “the images of the Divine had to visibly shift in order for more and more peoples to feel represented in a beatific vision and to feel connected to narratives that were intended to be universal”—that element “has always been, and remains, a key aesthetic tenet of American art.” He notes the circular Portrait of Petronila Méndez (1763), by Diego Antonio de Landaeta, depicting an expensively dressed young Afro-descendant child, “painted by an Afro-descendant artist of great skill. Both had agency, both had names and rights of address and respect accorded to those names,” he says. “The portrait disrupts the narrow view of black expertise and servitude that are still predominant in contemporary discourse.” Similarly, the unattributed Our Lady of Guadalupe at Extremadura (1730-80), connects the appearance of one of the “four great black madonnas of Europe,” revered “by so many people, especially those doing the work of religious and social justice,” he says, to the development of the “new world.”

It’s worth reserving a spot for one of Ballard’s gallery talks, where questions are appreciated. One visitor recently asked why he chose this as his first Harvard show. As a scholar and man of color, Ballard said, he felt compelled to “start at the beginning and make a show that, for the next 10 or 15 years, my colleagues can hold me accountable to. It felt important to model what it means to be accountable,” he added, “and to model how a show can raise more questions than answers—that we don’t have to be expert in everything. Deep curiosity, deep willingness to learn, is important.”