A glittering ballgown suspends in midair, center stage above a field of white flowers at the American Repertory Theater’s (A.R.T) revival of the musical Evita. With sunken shoulders, a funeral procession of dark-clothed women and men—some in uniform—carry lanterns, assuming positions within the rows of flowers. A bell chimes. Eyes transfixed on the ball gown, the soldiers salute, and a chant emerges from the crowd: “EVITA!” “EVITA!” “EVITA!”

Evita is “the story of a complex political figure who had an extraordinary rise and an extraordinary fall—and I would add the word ‘female’ to that somewhere,” according to the production’s director, 29-year-old Sammi Cannold, Ed.M. ’16. The musical, which runs at the A.R.T. through July 30, centers on First Lady of Argentina from 1946 to 1952, María Eva Duarte de Perón. Widely known as Eva Perón or simply as “Evita,” she—along with her husband, President Juan Domingo Perón—experienced both immense popularity among the Argentine working class and widespread criticism as an authoritarian ruler. Following her death at age 33, Eva Perón’s meteoric rise from humble origins to prominence immortalized her in popular culture. “But at the center of it, she was quite misunderstood from my own perspective—from what I've gotten to know,” said 24-year-old actress Shereen Pimentel, who stars in the titular role. Throughout a performance earlier this month, the production explored the intricacies of Perón’s character, posing the question “Was she an icon or a mortal, a villain or a saint, an aggressor or a victim?” as the production website puts it. “Who was the woman inside the iconic ball gown?”

Leah Barsky and Martin Almiron in Evita at American Repertory Theater

Photograph by Emilio Madrid

Though Evita first debuted in 1978, Cannold felt it had new relevance, especially given how the women’s movement has evolved in the decades since: “It’s a woman taking back her story after a man has told it for the entire time.” Time had opened space for a more nuanced interpretation of the title role as well. Cannold asked herself, “What would it look like to make a production that seeks to interrogate what she is feeling at any given moment?” Where other directors may have focused on the public-facing Perón, Cannold sought to explore: “What is the human journey alongside this icon journey?”

“Walking That Fine Line”

Cannold immediately felt the resonance of Evita, at the age of 18, when she saw the 2012 Broadway revival. She remembers being “knocked out” by the dialogue the production sparked—about an enigmatic woman driven by complicated desires for power and achieving a positive impact. Directing this revival is a full-circle moment for Cannold that began with an internship at the A.R.T., in which she “did everything from getting coffee to reading scripts to filing papers.” After her Stanford graduation, she returned to the A.R.T. as an A.R.T. Artistic Fellow and took on several assistant director jobs. She became the A.R.T.’s youngest female director in 2019 when she led the premier of Celine Song’s Endlings. Of directing Evita, Cannold said, “Because I grew up there essentially as a theater person, it feels like coming home.”

To better understand the history and enduring legacy of the Peróns, Cannold and Evita associate director Rebecca Aparicio traveled to Longchamps, a city 30 kilometers south of Buenos Aires. There, they met María Eugenia Álvarez, a 95-year-old nurse who had cared for Perón during her final days battling cancer. Álvarez shared that she held Perón’s hands as she passed away and then called on the two to give her their own hands. Cannold recalled her saying, “I want to hold your hand because I want to pass the energy from Evita to you.”

Evita Director Sammi Cannold, Longchamps, Argentina resident María Eugenia Álvarez, and Evita Associate Director Rebecca Aparicio

Photograph courtesy of Sammi Canold

“It’s moments like that where you understand Eva Perón was a person who affected the lives of so many people—in such significant ways that are still really potent to this day,” Cannold said, noting that insight from that conversation “was critical” to her conception of Perón’s character. “We have the responsibility of depicting the gravity of that, and I take that seriously.”

Cannold took four research trips to Argentina over the course of four years to interview individuals connected to Perón and the Peronist regime—including those who view Eva Perón as egomaniacal, manipulative, and politically corrupt. Pimentel said that “walking that fine line” between conflicting perspectives and “never deciding for the audience who she was” was the biggest challenge of embodying Perón, beyond maintaining her vocal stamina throughout the lavish “rollercoaster” of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s score.

“The Flow of the Evening”

The show’s design brought a contemporary twist to Evita’s artistic legacy. Featuring a dramatically enhanced set within the boundaries of a rectangular prism structure sectioned with five neon-lit doorways, it pays homage to Harold Prince's use of the "black box" concept in the original production of Evita. However, Cannold’s crew incorporated theatrical tricks and illusions into their rendition. Throughout the June 7th performance, an elevator built into the center of the stage lifted props to its surface within seconds. “It’s really about the flow of the evening and how you make people get lost in it,” Cannold said. “When you see someone moving a bed, you can take yourself out of the story and remember that it’s a play.”

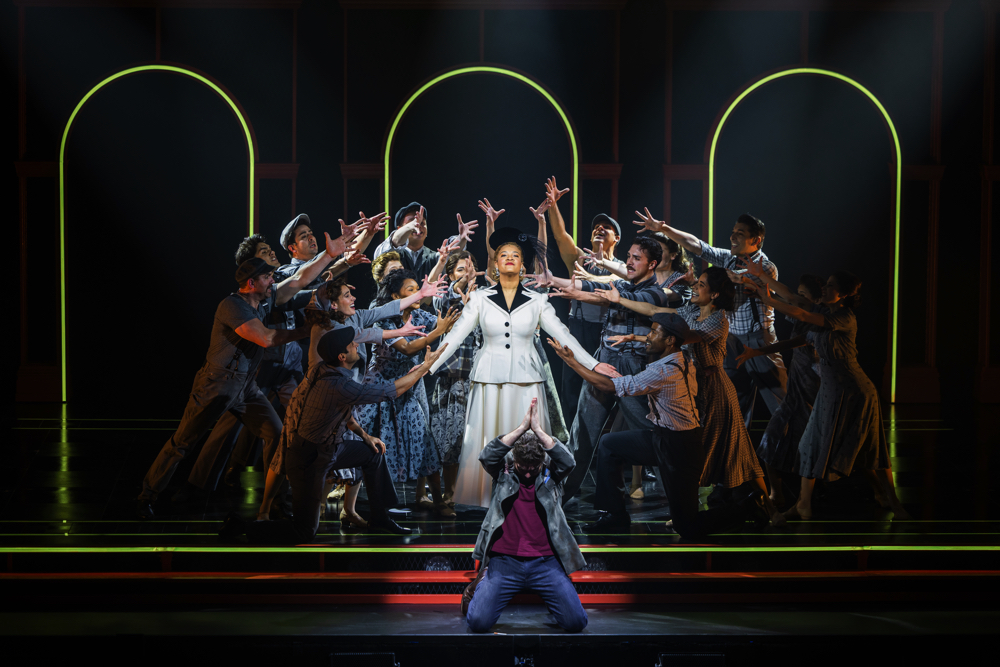

The company of Evita at American Repertory Theater

Photograph by Nile Scott Studio

The whimsical dynamics were anchored by the repeating motif of flowers: Perón’s sympathizers clutched bouquets at the opening funeral scene, and terraced beds of white flowers descended around Pimentel as she belted the iconic “Don’t Cry for Me Argentina.” Such choices were inspired by true events; people bought so many flowers for Perón’s funeral that Argentina suffered a shortage in the next days and had to import them from neighboring countries.

Working both behind the scenes and on stage is one of the most diverse theatrical crews in Evita history. Cannold said that in hiring the cast and crew, the team selected “whoever felt best for the job”; then, when they looked around, they realized “Oh my goodness, we’re all women.” There has never been “a first-class production of Evita that’s been directed or choreographed by a woman or an Argentinian,” Cannold said. “There’s a particular weight and responsibility that comes with that.”

Shereen Pimentel (Eva), Omar Lopez-Cepero (Che), and the company of Evita at American Repertory Theater

Photograph by Nile Scott Studio

Although the show was written by men, Pimentel said, “our version has the perspective of women for the entire thing—our direction, our music, and our choreography—and I think that that is such a beautiful way to reexamine the piece.” Cannold added, “It allows for an added layer of exploration into Eva Perón’s character. Being young women, we necessarily understand some of the things that Eva was going through from a first-hand perspective.”

Pimentel added that her own Puerto Rican and Jamaican heritage allows her to empathize with Perón’s struggle to be accepted by Argentinian society and interpret her character with additional depth. “Even though, somehow, she ended up being the icon of it all, she was shunned by aristocrats, and people kept trying to push her into different places,” Pimentel said. “I think that’s something you do feel as an Afro-Latin person unfortunately—not always feeling like you fit in a place where you want to and deserve to.”

Shereen Pimentel (Eva) and members of the company of Evita at American Repertory Theater

Photograph by Nile Scott Studio

Cannold praised the team’s diversity as its strength. Evita co-choreographer Valeria Solomonoff drew from her Argentine heritage to inform the production and incorporate traditional dance into the numbers. Not everyone in the cast and crew has extensive theater experience, either—such as the tango dancers, opera singers, and the 18-year-old actress portraying Juan Perón’s mistress, for whom this is her first professional production. These varied backgrounds enrich the show, Cannold said: “Any time you’re building a company, you’re trying to build a little microcosm of a family.”

Phenomenal or Terrible

The audience reception following the June 7th performance suggests that Evita has new meaning now, decades after its debut. “We’re all a little wiser and a little sadder now,” said Robert “Rob” Straus ’67, J.D. ’73, G.S.A. ’75, who first saw Evita a year after its Broadway debut in 1979. “The sadness comes through in this great production, and I think that’s a way Evita has changed—it matured over the years, and it fits now also with these times.”

Pimentel expressed her hope that the audience departs “curious about how someone could have lived their life this way,” “curious about a place that they’ve never been to or maybe don’t know the politics of,” and inspired to research further. She hopes that they react strongly to the show, whether positively or negatively. “‘Phenomenal’ or ‘terrible’ is better than, ‘I just had a good time,’” Pimentel said. “It means that you sat in the audience, you took in what we were doing, and there were thoughts running through your head for those entire two hours. That's when I feel like I did my job.”