Arthur Augustus “Fats” Johnson “has perhaps helped more colored youths than any other colored figure in Boston and Greater Boston.” So recalled black semipro baseball star William “Sheep” Jackson in 1945, reflecting on the contributions of a unique figure in the history of Boston baseball and of the Harvard of the 1920s and 1930s. Starting with nothing, Johnson made himself an entrepreneurial success in a largely segregated society while working to end the system in which he prospered.

Arthur Johnson was born in 1890 in Rockville, Maryland, the youngest of 13 children of a veteran of the 39th Colored Infantry of the Union Army. Arthur attended school for eight years before taking a job as a postal worker, unloading bags of mail from railroad cars until, as he put it, he was “bitten by the bug to see the country at the expense of the Pullman Company.” He spent the next five years as a porter on the elite 20th Century Limited. The opportunity to take side trips expanded his circle of acquaintances and his understanding of America.

As early as 1912, Johnson—an athletic 5’11”, 180 pounds before he earned his nickname—was playing baseball while off duty in Boston. The “Great Migration” of Southern blacks was bringing more African Americans to Roxbury, where several ball fields were available to all-black teams.

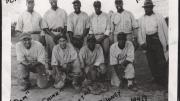

A decade later, Johnson was managing and promoting Boston’s most successful black baseball team, the Boston Tigers. He lined up opponents across New England and even in Canada. The “money man” for the team, he handled the business side of the games. The team was never fully professional, but as an allegedly amateur team, it could play games and collect receipts on Sundays, when professional games were banned. “Oh for the good ole Boston Tigers days when ole Carter Field was the haven of many a baseball classic,” “Sheep” Jackson told the Boston Chronicle in 1942, referring to what is now a Northeastern University athletic facility on Columbus Avenue.

Johnson made the transition from Pullman porter to baseball impresario with the help of connections he made at Harvard, where he became a celebrated figure for reasons unrelated to baseball.

Johnson’s Harvard career started modestly. Soon after arriving in Boston, he made the acquaintance of Bertie Davis, a black freshman from the class of 1917. An Exeter graduate, Davis had come to Harvard from Antigua in the British West Indies in the hope of becoming a lawyer either at home or in Africa. Lacking family resources, he got a scholarship from Harvard but was still short of money, so he started a laundry business at 19 Dunster Street. Johnson partnered with him in the business, overseeing the cleaning and pressing of countless Harvard men’s shirts. The “Varsity Shop,” Davis said, “proved to be so lucrative after the war” that with Johnson’s help he continued to run it, instead of finishing law school, until it collapsed in 1937 like many other Depression-era businesses.

After Johnson was discharged in 1919 from a short stint in a segregated U.S. Army unit, he re-engaged with both the laundry business and baseball. But he soon seized on a new moneymaking opportunity. Prohibition began in January 1920, and Harvard students were thirsty. Johnson—known as “Snowball” in Harvard circles—became “bootlegger, counselor, and legal adviser to students,” as he put it. His railroad connections facilitated his Canadian import business, and the wealth of his clientele (in the clubs and the old Gold Coast buildings along Mount Auburn Street) meant he could maintain quality standards—always sampling the goods for toxicity before delivering them. Reflecting on the change in students’ drinking habits after Prohibition, he said, “Then, they went more for the straight stuff with a little ginger ale or soda. They had pride in holding their own whiskeys. Now that the punch has come in, they start right off with the idea of getting drunk.”

Indeed, his punches were famous. A nostalgic naval officer stationed in the Canal Zone asked for Johnson’s “Green Dragon” recipe in 1941 so he could properly enjoy the radio broadcast of the Harvard-Yale football game. Johnson obliged, providing a recipe for 12 gallons of punch that included grain alcohol, rum flavoring, Cointreau, brandy, iced tea, ginger ale, and grapefruit juice.

Johnson tried to bring his talented players into competition with white major leaguers, but the effort was, he said, “like trying to mix oil with water.” He orchestrated games against white semipro opponents and several charity games against “Harvard All Stars”—alumni of Harvard’s baseball teams—for the benefit of a retirement home for elderly blacks. When black baseball faded in the 1940s, Johnson became valet—“private caretaker, weather-discusser, and day-starter”—to legendary Harvard English professor Charles Townsend Copeland.

In 1951, Johnson died and was buried in Boston’s Mt. Hope Cemetery, a self-described “old school” figure known equally to Harvard’s police chief and to the many Harvard alumni he befriended.