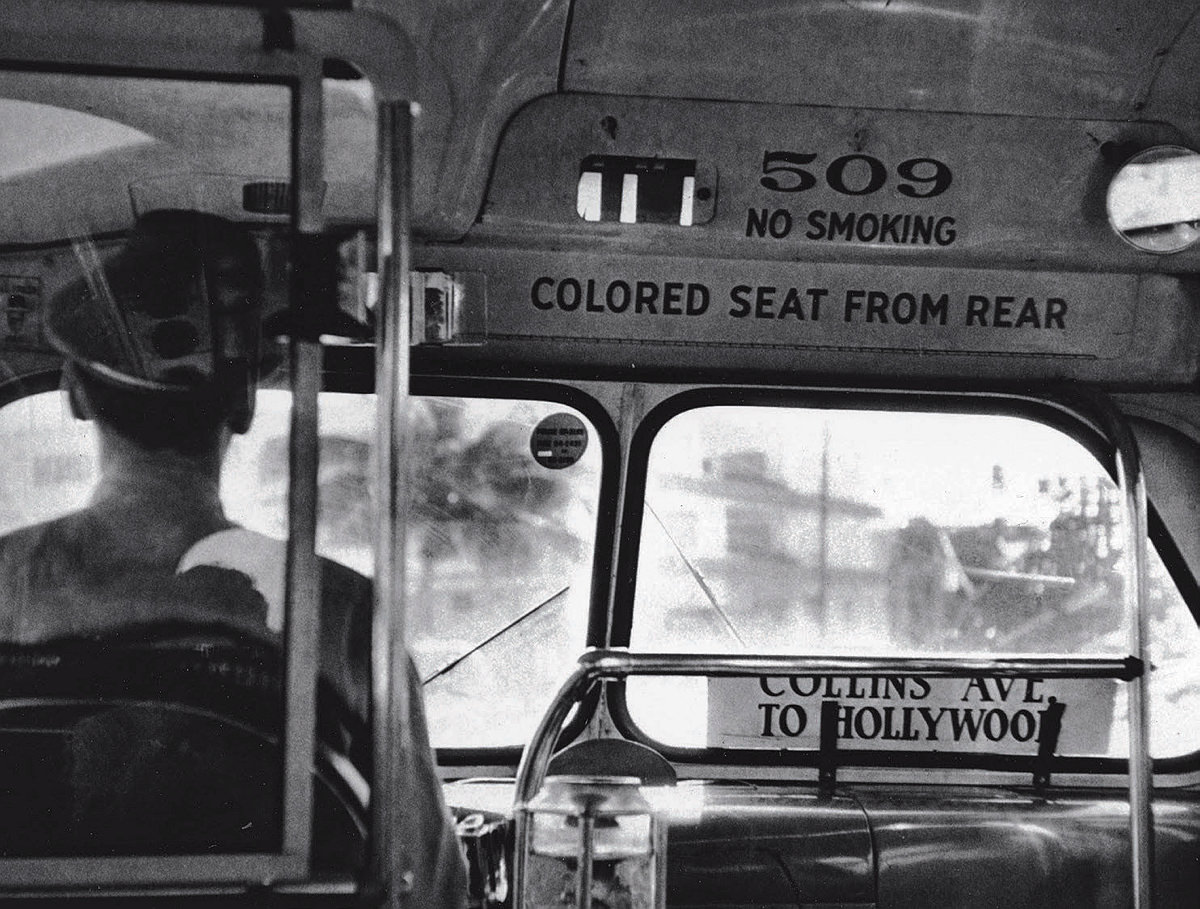

Most American schoolchildren learn about one Southern bus ride—on December 1, 1955, in Montgomery, Alabama, when Rosa Parks declined to cede her seat in the white section to a white man. Her refusal and ensuing arrest sparked the yearlong Montgomery bus boycott and catalyzed the civil rights movement.

But few people know about another Southern bus ride. Two decades earlier in Jackson, Mississippi, a six-months-pregnant woman named Jessie Lee Garner boarded a bus and took the last seat in the colored section. A few stops later, a white man got on the bus and, seeing all the white seats taken, demanded Garner give up her spot. Though it was illegal for the man to enter the colored section, Garner said she told him she “was heavy with child” and would give him the seat in two blocks when she got off. Unprompted, the man punched Garner in the face twice, knocking her to the ground. Her dental work fell out, her eyes swelled, and her unborn child died.

Reading Garner’s story in the Mississippi state archives, Myisha Eatmon sobbed.

Following the assault, Garner sued the company that operated Jackson’s buses. She and her attorney argued that the bus had not been sufficiently segregated—a sign separated the two sections rather than a physical partition, which state law required. An all-white jury awarded her $1,000 (about $22,000 today) to cover her “medical services, to pay nurses, [and] to pay servants to do her ordinary work,” and because she “suffered great pain and mental anguish.”

Eatmon, assistant professor of African and African American studies and of history, understood that a black woman suing after an attack defies the common perception of the Jim Crow South. She wanted to know more: Why did Garner press charges in civil rather than criminal court? How did she find out that she could sue, despite having no legal education? More broadly, were other African Americans suing to get redress for white violence?

Eatmon’s research is part of the continuing excavation of how African Americans exercised agency during a legal and social regime designed to oppress them. (See the related features, “Fugitive Pedagogy,” March-April 2022, on black schooling, and “Both Sides Now,” January-February 2022, on the civil rights movement.) In the Jim Crow South, legal and social systems prevented black people from protecting their rights in court. But Eatmon uncovered some black lawsuits that tell a different story. In 200 cases that she examined—a small slice of all black-initiated litigation—African Americans asserted their rights to exist free of white violence. Eatmon’s work, says professor of African and African American studies Jesse McCarthy, could “change how we understand the civil rights movement, which is so famously reliant on legal cases.” To find this hidden history of black agency, Eatmon mined previously understudied sources.

During the Jim Crow era—ranging from the end of Reconstruction to the 1965 Civil Rights Act—political, legal, social, and economic systems rendered African Americans second-class citizens nationwide, particularly in the South. One of the most dramatic sites of racial discrimination, Eatmon argues, was the criminal courtroom. In the Jim Crow South, where violence against black people was socially acceptable, few criminal courts would convict white people for harming African Americans.

But the law is not a monolith. If a white person were to face consequences in criminal court for anti-black violence, Eatmon says, a jury would have to find the defendant guilty of an injury against the public. In civil court, however, a jury must only find the defendant guilty of an injury against an individual. So, African Americans could bring tort cases—suits against corporations or people that caused them harm—and win compensation for injuries, even if the attack was not necessarily determined to be illegal.

While writing her history dissertation at Northwestern University and conducting research for her forthcoming book, Eatmon uncovered a vast history of African Americans filing tort claims against white attackers. Even though few of them had access to legal education, she found, black Southerners initiated a robust body of lawsuits. The cases were impressive, and she wanted to know more about how these black Southerners grew to understand the law. She turned her attention toward black newspapers, whose legal sections spurred the “democratization of legal education,” she says, and created what she calls a “black legal culture.”

This rich history of black civil suits surprised Eatmon’s mentors. “In many people’s minds, [the Jim Crow era] is a period when African Americans have been abandoned by the Constitution,” says Martha Biondi, a history professor who served on Eatmon’s dissertation committee. “It is not a time, typically, when you would think of African Americans seeking any kind of redress through the law or having any hopes…that they could prevail in any legal struggles.”

From a young age, Eatmon has been troubled by injustice. She learned about the Holocaust and slavery in her Chapel Hill, North Carolina, schools. “I didn’t really understand,” she says, “how people could just kill other people because they didn’t look like them or believe in the same religion.”

Eatmon’s parents were separated, so she lived with her mother and her maternal grandfather, who had moved to Chapel Hill from a plantation in Chatham County, North Carolina, during the Great Depression. Though her grandfather would frequently tell stories from his World War II service, he never talked about racism back home. “The mythology was that Chapel Hill…may have been segregated, but it wasn’t racist,” she says. “I had this itch to learn more about what Chapel Hill was like during Jim Crow.”

During her undergraduate years at the University of Notre Dame, Eatmon began investigating the nation’s past. She studied history and political science (all while working 40-plus hours per week in the dean’s office and at local restaurants). She considered law school, and spent her junior fall interning for Senator John Kerry’s Washington, D.C., office, but chose to attend a history Ph.D. program instead. Talking with a mentor, she says, convinced her “that I could touch more lives in the classroom than I could as a litigator.”

In 2014, just before the third year of her graduate studies, Michael Brown was killed by Ferguson, Missouri, police officer Darren Wilson. To Eatmon, Brown resembled her younger (half) brother, Jacobie Lewis. Just a middle schooler, Lewis was already around 250 pounds—“a big black boy,” she says. “It felt as though the police were always a threat,” she continues. “If they could do it to Michael Brown, then they could do it to my brother.” She took her anger to the streets, protesting on the South Side of Chicago.

A year after Brown’s death, Eatmon submitted her dissertation proposal. By then, a grand jury had declined to criminally indict Wilson, and Brown’s family filed a suit against the city of Ferguson for wrongful death. The city’s insurer would eventually pay the family a $1.5-million settlement. The difference between the criminal and civil outcomes led Eatmon to wonder, “Have black people always had to sue to gain legal recourse for white violence?”

She wanted to write a legal history, but she was not a lawyer, and history Ph.D. programs do not teach torts. Conveniently, her dissertation adviser, Dylan Penningroth, was working on his own black legal history. Each week, he’d assign Eatmon a stack of cases. Sitting with Penningroth, she would “gut a case,” she says, “the way that one would do in law school.” With her new legal knowledge, she got to work.

Though Jim Crow-era African Americans sued for personal benefit, Eatmon contends that they unknowingly helped secure civil rights for all. That argument would surprise those plaintiffs, who—until the 1950s and ’60s—often went to great lengths not to argue through a civil rights lens. Rather than asserting their rights as citizens, Eatmon says, African Americans in Jim Crow-era civil suits argued that violence violated their rights of personhood—to live free of bodily harm.

When attacked on buses and railroads, for example, black plaintiffs asserted that their rights as passengers were violated. The common law surrounding mass transit protected travelers equally, regardless of race. By presenting as passengers, not solely as black people, African American plaintiffs appealed to white juries. Most passengers were white and, Eatmon says, “Everybody hated the bus company [and] the railroad company.” When black plaintiffs sidestepped race, she argues, white juries were more likely to hold transit corporations responsible for onboard violence.

Even when adopting a race-blind stance, black plaintiffs tried to prove that they were docile and well-mannered, playing against the racialized public perception that African Americans were wild and dangerous. In part, this strategy was legal; if a white person acted out of self-defense, his attack might be considered reasonable, and therefore not merit a payout. But Eatmon finds that a significant reason to posture innocently was social. Jim Crow—according to legal historian Royal Dumas, whom she cited in her dissertation—required “African Americans to be ignorant, docile, and unthreatening.” White juries, Eatmon says, treated black plaintiffs paternalistically, in need of protection: plaintiffs who showed weakness were often granted mercy.

Even following those strategies, African Americans did not always win their cases. In July 1886, a white conductor shot a black man named Joseph Jopes while aboard a train in Nicholson, Mississippi. The conductor alleged that Jopes was threatening him with a knife. Jopes—in the style of other black plaintiffs—claimed that he was non-threatening, saying that he was just cleaning his nails and that he and the conductor had been joking with each other when he pointed his pocketknife. After Jopes sued the company for damages, his case made its way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in the railroad’s favor, holding that companies are not liable for actions their employees commit under “a reasonable belief of immediate danger.”

When African Americans like Jopes were attacked by white employees, they sued their attackers’ employers and the agencies that insured those companies. Eatmon says targeting such entities had two major benefits: groups had more money than individuals, and—facing economic penalties—these stakeholders could be induced to change behavior. During Jim Crow, police officers were rarely criminally punished for violence. Attorneys did not want to prosecute them, and juries did not want to indict or convict them, according to Eatmon. But tort suits seem to have created a natural check. Suing police departments’ surety companies, she says, pressured them to “think critically about the types of men they insured.” Some companies avoided insuring police due to the threat of tort cases, so police departments were incentivized to discourage violent behavior.

How did the vulnerable plaintiffs in these cases figure out how to navigate the tort system? There were some black lawyers (about 800 in 1910, some 0.7 percent of the nation’s attorneys), but many of them practiced in the North, where the social and political environment was friendlier. Given the paucity of black lawyers in the South, Eatmon credits two institutions with building a “black legal culture”: black newspapers and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She coined that phrase to describe the ways that African Americans think about, interpret, and use the law to “meet the needs specific to oppressed or marginalized black people.” During Jim Crow, people steeped in black legal culture understood legal vocabulary and knew which institutions treated African Americans (relatively) fairly. The black legal culture forged in that era, she says, “changes, morphs, and evolves,” but still exists. As a modern example, she points to “black Twitter,” where people protesting the murder of George Floyd in 2020 could find information about their rights and what to do if arrested.

In black newspapers, she found a robust archive of black legal knowledge. Some papers covered cases in a straightforward fashion—just the facts. Others added editorial comments and offered legal advice to readers and prospective plaintiffs. Those papers, Eatmon says, “are sassy—they have really strong words,” covering not only the facts in a case but also the culture of white-on-black violence it exemplified. Some newspapers’ legal dissemination went beyond writing; in Chicago, The Defender had a legal department that ran question-and-answer columns and provided one-on-one help. But other organizations were better suited to cater to individual needs.

Much of the NAACP’s reputation derives from its high-profile test cases like Brown v. Board of Education. Eatmon highlights a less famous function of the organization: connecting black individuals with reputable lawyers. Though civil courts in the Jim Crow South were friendlier to African Americans than criminal courts, black plaintiffs still struggled. Sometimes, Eatmon says, their white lawyers would play “inside baseball” with the judge and other white lawyers to work against the injured African American’s interest. Other times, subpar lawyers would misrepresent their plaintiff’s case. Black people often wrote letters to the NAACP’s national office seeking legal advice, hoping the organization could serve as a “litmus test for who would be a good or trustworthy lawyer,” says Eatmon. Though the organization rarely took on such cases, NAACP staffers referred the letter-writers to lawyers who were not NAACP employees but often had worked with the organization.

Though responding to such letters was far from the NAACP’s primary mission, Eatmon argues that this legal networking—and the black torts that followed—helped protect black civil rights. The lawyers and plaintiffs in these tort cases likely did not think they were advancing civil rights: the lawyers, Eatmon says, saw them as opportunities to make money, since they charged a retainer or took a piece of the financial reward. But she argues that such cases, in fact, did defend and expand black rights.

Eatmon didn’t write her dissertation under normal circumstances. In June 2015, following her third year of graduate school, she returned home for her younger sister’s high school graduation. There, she found that her mother—battling breast cancer—was in far worse condition than she had known. After the graduation, Eatmon flew back to Chicago, packed her car, and drove home.

At first, she intended to split time between Chicago and Chapel Hill. But in August, she moved home. A few weeks later, her mother died. Her sister was slated to begin college that week, and her brother high school. Because Jacobie Lewis’s father was not involved in his life, his mother’s death left him without a guardian. While Eatmon had planned to spend the next few years teaching, researching, and writing, she instead became a parent. She helped Lewis with school, made sure he was fed, and brought orange slices to his football games. “It’s tough when you lose your mother and you have to be the mother,” says Lewis. “I thank her every day for giving me the chance to have a normal life.”

After taking one year off from school, Eatmon began writing her dissertation. Because she had to take care of Lewis, she narrowed the scope of her research. Rather than look at all tort cases involving white-on-black violence, she examined 200 Jim Crow-era appeals (cases that reached state supreme courts, federal appellate courts, or the U.S. Supreme Court), because those records were reliably available online.

While living in Chapel Hill, Eatmon also worked full time at the dean’s office at the University of North Carolina School of Law. There, students told her they wanted to learn more cases brought by people of color, but professors said they would only teach from the casebook. “It’s really easy to find these cases if you know where to look,” she says. “It’s important to include cases where race is involved when teaching something like torts, which could be colorblind or race neutral.”

“Even though there’s an erasure of race from a lot of these cases when the opinions are written,” she says, “those black people’s experiences are still a part of building tort case law.”

Her experience at UNC Law inspired the final chapter of her dissertation, which assessed black plaintiffs’ impact on tort doctrine. Eatmon argues that the field of tort law “came of age” alongside Jim Crow in the late nineteenth century. “Even though there’s an erasure of race from a lot of these cases when the opinions are written,” she says, “those black people’s experiences are still a part of building tort case law.”

The importance of including African Americans in tort history extends beyond diverse representation; when black cases from the Jim Crow era are used as precedent, Eatmon says, racism becomes embedded into American law. The Joseph Jopes case, where a white conductor shot a black passenger, has been cited by courts 113 times, and limits employers’ responsibility for the actions of their employees. Suits like Jopes, Eatmon says, “are not leading cases in the same way that some of the cases taught in law school are, but I do think that more law professors could teach torts with race in mind.” She writes, “Should a jurist, attorney, legal scholar, or historian consult the United States Supreme Court record of Jopes, she will find a snapshot of how Jopes experienced his Blackness, his humanity, and oppression under Jim Crow, in his own words.”

After shepherding her brother through four years of high school and earning her doctorate, Eatmon joined the faculty of the University of South Carolina. Following a one-year research fellowship, she taught there for two years before coming to Harvard in 2022. Now, in her Barker Center office, she thinks about her book, tentatively titled Litigating in Black and White: Black Legal Culture, White Violence, Jim Crow, and Their Legacies, which she plans to complete while on leave next year. As she writes, she looks down at her wrists, and the tattoos on each.

Her left wrist reads It is written. She got the tattoo in 2015, the year of her mother’s death. It is a reminder, she says, “that the story didn’t end with my mom passing away…[and] that the dissertation would get written. It’s a reminder that the book will get written, too.”

Her right, inked in 2018, reads Break every chain. “I struggled a lot after my mom passed away. It was a reminder that God hadn’t left me and that I wasn’t going to be stuck forever. Being back in my hometown wasn’t always easy.”

That right wrist tattoo also reflects her work. African Americans may have broken the chain of slavery in 1865, but it was another century until the Civil Rights Act ended their unequal legal treatment. In the interim, as Eatmon has shown, they sued for their rights.