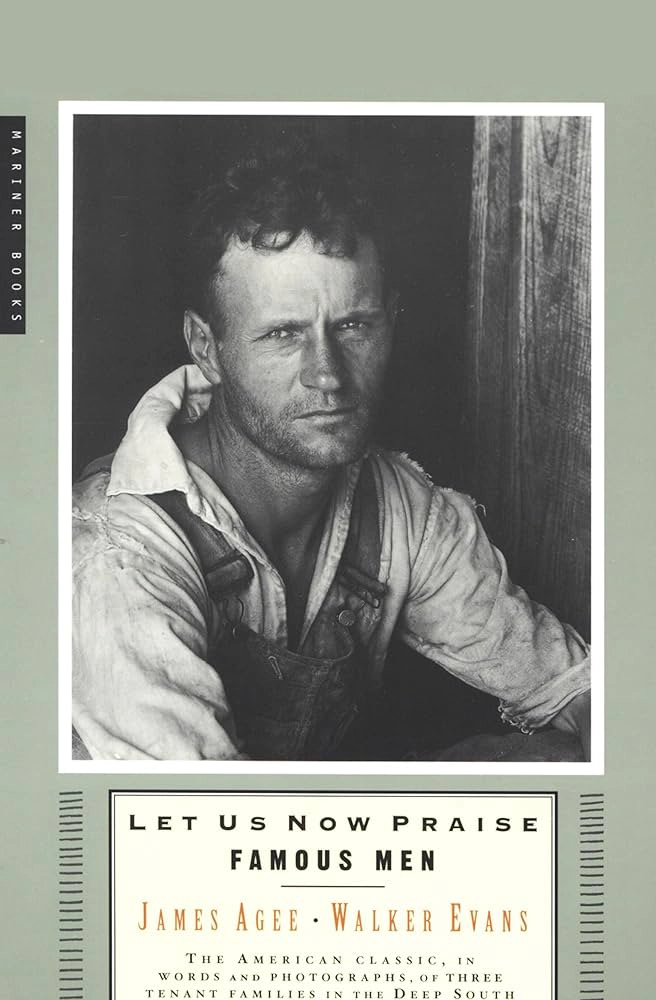

When he was running for president in 1976, Jimmy Carter was asked to name his favorite book. He said, “strangely enough,” it was Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, with text by James Agee ’32, and photographs by Walker Evans, published in 1941 when Carter was 17.

Why strangely enough? The book and its history explain. It was reported, written, and rejected as a 30,000-word piece of journalism titled “Cotton Tenants: Three Families” for Fortune magazine in 1936. It was called “a distinguished failure” in a Time magazine review when it arrived as a 471-page book four months before the United States entered the Second World War, sold just 600 copies in its first year, and was soon remaindered.

Agee had first used the “Praise” title for a short story. He took it from the King James version of the Bible—“Let us now praise famous men, and our fathers that begat us”—ironically as the book title, because the families were then the opposite of famous. But as Agee wrote, they were “chosen with all possible care fully and fairly to represent the million and a quarter families, the eight and a half to nine million human beings, who are the tenant farmers of the cotton belt,” which was, he explained, “sixteen hundred miles wide and three hundred miles deep.”

The book is about the lives of three white families that raised cotton in central Alabama, based on eight weeks Agee and Evans spent with them in the summer of 1936, during the seventh year of America’s decade-long Great Depression. As halvers, or sharecroppers, they leased from their landlord their cabin, land, farm tools, and mule or mules: at the end of each year, they owed the landlord half their crop of cotton and corn and any money they had borrowed for food, seed, and so forth—an arrangement that Agee called “a dizzy mix of feudalism and of capitalism in its latter stages.”

During the 1976 presidential campaign, the filmmaker Ross Spears interviewed Carter, then 51 and wearing a cowboy shirt and jeans held up by a belt with a big silver buckle, for his hour-and-thirty-eight-minute-long documentary film Agee: A Sovereign Prince of the English Language. The subtitle was a moniker of nobility bestowed by the editor, writer, and translator Robert Phelps.

By then, Carter had graduated from the United States Naval Academy, served six years as a naval officer, been elected to two terms in the Georgia state senate, and served a term as governor. But he had grown up on a 350-acre farm, 120 miles from Atlanta, in an unincorporated rural community called Archery since made part of Plains. Until he was 14, he lived in a house without electricity or running water. The farm grew peanuts, cotton, sugar cane, and corn to sell, raised vegetables and livestock for the family, and sold hams, pork shoulders, and sausage cured in the smokehouse.

In 1975, Carter recounted, “My black playmates were the ones who joined me in the field work that was suitable for younger boys. We were the ones who ‘toted’ fresh water to the more adult workers in the field. We mopped the cotton, turned sweet potato and watermelon vines, pruned deformed young watermelons, toted the stove wood, swept the yards, carried slop to the hogs, and gathered eggs—all thankless tasks. But we also rode mules and horses through the woods, jumped out of the barn loft into huge piles of oat straw, wrestled and fought, fished, and swam. The early years of my life on the farm were full and enjoyable, isolated but not lonely. We always had enough to eat, no economic hardship, but no money to waste. We felt close to nature, close to members of our family, and close to God.”

Agee came out in 1980 and was a nominee for an Academy Award the following year. Carter has a cameo in the film.

“I don’t know exactly why I liked the book so much,” Carter begins on camera: “One of the reasons is that the life that he wrote about was almost exactly the life that I knew. We were not as poor, but my neighbors were, and his detailed description of most specific occurrences or observations of his and his projections on a universal basis of the suffering and destitution of people who were afflicted by poverty really touched my heart.”

Carter was impressed by Agee’s “reticence about intruding on these people who were so weak and unsure of themselves that they would not have excluded him even if they wanted to. They thought he was maybe a dominant figure. He wanted to be so careful not to disturb their lives, not only because he didn’t want to paint a false picture of how they lived, but also because he respected them and cared about them and felt that their privacy was one of the few precious possessions that they had that was all their own.”

In appreciations of Carter since his death in late December, there have been mentions of his voraciousness as a reader and his affection for Agee’s writing. The latter assume the reader knows who Agee was and why he was a sovereign prince. Those are dubious assumptions. Agee died in 1955, or 70 years ago, and never achieved the scale of success of peers like William Faulkner and Ernest Hemingway or of major influences on him, like James Joyce and Fyodor Dostoevsky. The breadth of Agee’s writing also meant that he didn’t command attention by experts or readers in one genre.

But his writing is worth knowing about and reading today: It’s lyrical and lush, sometimes clotted, sometimes lean, and often elaborate and headlong. It’s old-fashioned, influenced by the Bible in language and form, with “Elizabethan colors,” as Evans put it, yet modern because it’s so expressive of the human senses, especially sight and sound. In Agee, Carter says, “I believe he added a new dimension to descriptive literature.” [Read Adam Kirsch’s appreciation, “Vistas of Perfection,” May-June 2009.]

When writers talk about voice, they usually mean what writing sounds like, but a more accurate explanation is how writers take in the world—what they observe and how they filter it—and then how they express it. The fiction writer and journalist Adam Haslett called the way Agee took in the world “strenuous empathy” and what he expressed about what he observed and felt “a kind of morally indignant anthropology,” in the “manner of Jesus strained through Marx.”

Agee’s voice sounds textured in part because it weaves contradictory strands: one reflects his belief that his task as an artist was to describe “actuality”—“the cruel radiance of what is”; another made clear his concern that each view of actuality was subjective and biased; and a third showed the power nonetheless of his fervent curiosity and of his longing to capture and convey truth, which he expressed in a line of Sonnet XV in Permit Me Voyage: “High-souled in joy and hungry for the fight.”

In Agee, Spears asks Carter what he tells friends when he recommends Praise. He says, “I generally warn them about it and say, ‘Just relax and read the book like it’s poetry.’” Much of Agee’s writing, with meter and music, meticulous detail, and metaphysical ideas, is poetic.

He won the Yale Younger Poets Award at 24 while he was working as a reporter for Fortune. The collection that Yale University Press published in 1934, called Permit Me Voyage and the only book of his poetry published when he was alive, begins with this epigraph to an eight-page “Dedication”: “in much humility/to God in the highest/in the trust that he despises nothing.” The great translator, literary critic, poet, and longtime Boylston professor Robert Fitzgerald ’33, who was a close friend of Agee’s and edited a later collection of Agee’s poems, called Voyage “an openly religious book of poems.” The book, like much of his writing, documents conflicts—about what’s fair, about history, and especially about love of all kinds.

In his thirties, Agee won acclaim for his movie criticism in the Nation and in Time. In his early forties and the last chapter of his life—he died of a heart attack in a taxicab in New York City at 45, in 1955—he wrote film scripts and fiction. He wrote, for example, the screenplay for The African Queen (1951), with the movie’s director John Huston, based on a novel by C.S. Forester.

Agee’s autobiographical novel A Death in the Family was published two years after he died and won a Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The play All the Way Home, adapted from the novel by Tad Mosel, won a Pulitzer Prize for drama. A central character is a boy named Rufus, Agee’s middle name and what he was called as a boy. The character’s father is killed in a car accident when Rufus is six, as Agee’s was when he was that age: the novel is about how the family copes with that out-of-nowhere death. It opens with a prose poem, “Knoxville: Summer, 1915”—Agee was born and the novel is set there—and this incantation: “We are talking now of summer evenings in Knoxville, Tennessee, in the time that I lived there so successfully disguised to myself as a child.”

In 1960, with the prominence of the novel after Agee’s death, Praise was rediscovered, brought out in a handsome new edition with a foreword by Walker Evans, and celebrated as a classic documentary work. Evans called it “a great book” and “a rather spectacular instance of resuscitation of cast-off material.” It contains 62 black-and-white prints of what he termed his “straight photography.” Peter Galassi ’72, who was chief curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art for 20 years, extolled his photographs as among the most influential in the twentieth century, with the work he did in Alabama some of his most important.

The Evans foreword is as incisive and revealing as his photographs. He noted about the 26-year-old Agee, whom he had worked with when he was 32 during that summer of ’36, “Like many born writers who are floating in the illusory amplitude of their youth, Agee did a great deal of writing in the air. Often you had the impulse to gag him and tie a pen to his hand. That wasn’t necessary; he was an exception among talking writers. He wrote—devotedly and incessantly.”

In 1962, joining the gamut of his unicorn-like books, came Letters of James Agee to Father Flye, reflecting a friendship that lasted until Agee died. It began when, at almost 10 and as a boarding student, he went to St. Andrew’s School, near Sewanee, Tennessee, and Father Flye, an Anglo-Catholic, or Episcopal, priest and history teacher at the school, was 35. In the “Dedication” to his poems, Agee included him as “James Harold Flye, priest, who befriended my boyhood with the wisdom of gentleness.” Father Flye, like Carter, lived to 100.

In an exquisite memoir about Agee, Fitzgerald, who knew Agee’s other writing well, called Praise “the center piece in the life and writing of my friend.” From February 1930, when the two met as undergraduates in a Harvard English class and Agee embodied “shyness and power and imagination,” until his friend’s death a quarter of a century later, Fitzgerald took his measure as a peer—in intellect, sensibility, faith, and the pursuit of truth, which, he wrote, was “destined to haunt us like a Fury.”

He judged that Agee had “two principal gifts” as a writer: “a capacity for major musical form, the sustained and various shaping of movement in time”; and “a sense of being,” which was “a raging awareness of the sensory field in depth and in detail.” When Praise was reissued in 1960, Fitzgerald later wrote, looking back at that moment, “the peculiar strength” of Agee’s writing was usually assessed as “range of awareness, moral passion, and visualizing power.” In 1972, not long before Carter spurred a second revival of interest in Praise by singling it out, Fitzgerald said “the principal value” of Agee’s writing in that “center piece” were “such literary terms as discipline, delicacy, precision, and scruple.”

In a preface to Praise, Agee wrote:

The nominal subject is North American cotton tenantry as examined in the daily living of three representative white tenant families.

Actually, the effort is to recognize the stature of a portion of unimagined existence, and to contrive techniques proper to its recording, communication, analysis, and defense. More essentially, this is an independent inquiry into certain normal predicaments of human divinity.

The preface suggested that a reader read the text almost continuously, explaining why:

The text was written with reading aloud in mind. That cannot be recommended; but it is suggested that the reader attend with his ear to what he takes off the page: for variations of tone, pace, shape, and dynamics are here particularly unavailable to the eye alone, and with their loss, a good deal of meaning escapes.

It was intended also that the text be read continuously, as music is listened to or a film watched, with brief pauses only where they are self-evident.

The text opens with this line and a half in verse, dedicated to Evans: “Against time and the damages of the brain/Sharpen and calibrate.”

Soon, Agee described the people he was writing about as “an undefended and appallingly damaged group of human beings,” but emphasized that he would do his best to let them shape their stories—which he did, with compassion, anger on their behalf, and sometimes awe.

In a novel, a house or person has his meaning, his existence, entirely through the writer. Here, a house or a person has only the most limited of his meaning through me: his true meaning is much huger. It is that he exists, in actual being, as you do and as I do, and as no character of the imagination can possibly exist. His great weight, mystery, and dignity are in this fact.

He added:

‘Above all else: in God’s name don’t think of it as Art.

Every fury on earth has been absorbed in time, as art, or as religion, or as authority in one form or another. The deadliest blow the enemy of the human soul can strike is to do fury honor.

And:

Here at a center is a creature: it would be our business to show how through every instant of every day of every year of his existence alive he is from all sides streamed inward upon, bombarded, pierced, destroyed by that enormous sleeting of all objects forms and ghosts how great how small no matter, which surround and whom his senses take: in as great and perfect and exact particularity as we can name them:

Then there are his subjects:

In the square pine room at the back the bodies of the man of thirty and his wife and of their children lay on shallow mattresses on their iron beds and on the rigid floor, and they are sleeping, and the dog lay asleep in the hallway.

And:

The young man’s eyes had the opal lightings of dark oil and, though he was watching me in a way that relaxed me to cold weakness of ignobility, they fed too strongly inward to draw to a focus: whereas those of the young woman had each the splendor of a monstrance, and were brass. Her body also was brass or bitter gold, strong to stridency beneath the unbleached clayed cotton dress, and her arms and bare legs were sharp with metal down. The blenched hair drew her face tight to her skull as a tied mask; her features were baltic. The young man’s face was deeply shaded with soft short beard, and luminous with death. He had the scornfully ornate nostrils and lips of an aegean exquisite. The fine wood body was ill strung, and sick even as he sat there to look at, and the bone hands roped with vein; they rose, then sank, and lay palms upward in his groins. There was in their eyes so quiet and ultimate a quality of hatred, and contempt, and anger, toward every creature in existence beyond themselves, and toward the damages they sustained, as shone scarcely short of a state of beatitude; nor did this at any time modify itself.

And:

From these woods a good way out along the hill there now came a sound that was new to us.

All the darkness in near range of the earth as far as we were able to hear was strung with noises that were all one noise, and to this we had become so accustomed that this new sound came out of silence, and left an even more powerful silence behind it, so that with each return it, and the ensuing silence, gave each other more and more value, like the exchanges of two mirrors laid face to face.

Whereas we had been silent before, this sound immediately stiffened us into much more intense silence. Without exchange of word or glance we each received communication of a new opening of delight: but chiefly we now engaged in mutual listening and in analysis of what we heard, so strongly, that in all the body and in the whole range of mind and memory, each of us became all one hollowed and listening ear.

After Carter’s death, his biographer Jonathan Alter ’79 wrote in the Times:

Throughout his long life, classmates, colleagues, friends and even members of his own family found him hard to read. The enigma deepened in the presidency. From my observations and from those of the people who worked for and with him in Atlanta and Washington, a complicated picture emerges. I concluded that Carter was a driven engineer laboring to free the artist within. He once told me that he could express his true feelings only in his poetry, which he wrote after leaving the presidency.

Carter’s public life was full of evidence of his interest in and commitment to poetry. As Georgia’s governor, he appointed poet laureates. The Georgia poet James Dickey, at his request, composed a poem to commemorate his swearing-in as president. In January 1980, he and the first lady hosted the first celebration of American poets and poetry held at the White House.

Yet his conviction about the importance of Praise reflects most of all the nourishment and provocation, the expansion of horizons, and the human and spiritual connection that Carter found in reading it—with the brief against economic and social injustice moving him as much as the poetics of the writing. Agee’s “detailed description of most specific occurrences or observations of his and his projections on a universal basis of the suffering and destitution of people who were afflicted by poverty really touched my heart,” the soon-to-be president said. The verse about famous men in the King James version, from which Let Us Now Praise Famous Men was titled, ends like this: “Their bodies are buried in peace; but their name liveth for evermore.”