Damages associated with increasingly severe climate-related wildfires, floods, and hurricanes are compounding America’s critical housing affordability crisis. The U.S. home price index jumped 46 percent from the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic to last year. Add to that a budding insurance crisis driven in part by climate change, and a history of reactive rather than forward-looking federal policy responses—these are the ingredients of a crisis. In a March 25 briefing, Carlos Martín of Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies (JCHS), alluded to this risk as he spoke about the current state of climate adaptations in relation to U.S. housing. He cited the role of expensive retrofits in vulnerable regions raising the costs of homeownership, stricter building codes that necessarily make construction of new homes more expensive, and higher insurance costs—all propelled by the changing climate. On March 28, JCHS postdoctoral fellow Steven Koller followed with a detailed analysis of climate change impacts on the residential insurance market, where, he said, “many people are really starting to connect the dots between the impacts of climate change and their own pocketbooks.”

Mounting Disasters, Rising Costs

Wildfires in the West have become more frequent and intense sooner than originally predicted. And wildfire damage to homes is no longer confined to those states: between one-third and one-half of U.S. wildfires in 2023 and 2024 burned in the Southeast. Recent hurricanes such as Helene and Milton that leveled trees in parts of the South, littering wide areas with downed fuel, may contribute to even more destructive blazes during the next fire season.

Similarly, hurricanes carry more moisture over greater distances and produce more wind than in the past, causing floods that have destroyed homes from Vermont to Texas. In coastal regions, where hurricane-driven storm surges cause more damage because global sea level is higher, some banks have begun to sell off mortgages in risky areas threatened by extreme weather.

These factors have begun to affect where people choose to live, and have had an impact on national economic growth. And it is clear that financing climate adaptations and deciding what to let go will become a challenge for many communities.

“Attribution science after an acute event is becoming more precise,” said Martín. “There is strong evidence that the combination of high heat, dry climate, and forceful winds brought on by climate changes made the [Los Angeles] fires roughly 35 percent more likely.” The combined property and capital losses for those fires have been estimated at $76 billion to $131 billion, of which “potentially only about $20 billion” was insured. Housing damages are growing across the country, he said, reflecting both “the severity of events as well as the high values of properties in harm’s way, especially urban property in areas with unprecedented housing availability and affordability crises like Los Angeles.” Spending on disaster repairs has risen to $23 billion annually, representing more than 6 percent of the total expenditures nationally for housing repair and improvement. Martín added that along with insurance, federal disaster aid is one of the two “primary ways that homeowners and households have been able to rebuild.” The “unprecedented politicization and potential withholding of federal disaster aid,” he said, combined with “presidential executive orders and media signals [that] point to a dismantling of the Federal Emergency Management Agency,” suggest that the economic burden of post-disaster recovery will fall squarely on insurers and policyholders themselves.

Both the Biden and first Trump administrations proposed national climate resilience strategies, but Martín said that the nation has not had a climate adaptation policy for housing. Instead, he emphasized, “what we did have primarily was disaster policy” created in response to mass property damage, rather than prescient strategies for protecting or relocating the most vulnerable housing stock.

The record of U.S. policy responses to disasters reveals this reactive, rather than forward-looking, national stance. Martín cited five events, from the Great Mississippi Flood (1927) through Superstorm Sandy (2012) and the Mill Fire in rural California (2022) and said they had yielded responses ranging from the creation of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) to recent questions about whether certain communities would want to rebuild in the same locations at all.

The history, says Martín, demonstrates that “climate adaptation policy in the United States today is largely built on disaster policy,” underpinned by the Stafford Act of 1988. In this context, risk assessment has fallen largely to insurance companies, because most home buyers (unless they are purchasing with cash) must have insurance to qualify for a mortgage loan. But an increasing proportion of homeowners can’t access insurance, either because insurers won’t cover their property or because they can’t afford the cost of a policy. “It could get to that point where it becomes a severe financial crisis,” says Martín, “because the risks are so high.”

The Costs of Adaptation

Homeowners and prospective home buyers can now find local data for climate risks such as wind, flood, and fire on home sales sites such as Zillow and Realtor.com. “But we know that regardless of information,” Martín continues, “some households simply have no choice but to buy the riskier homes.” And homeowners rarely invest in mitigation before disaster strikes, even in risk-prone areas. Raising homes above floods, strengthening roofs, and landscaping to prevent wildfires, Martín notes, “takes a lot of work and expense.”

The simplest form of adaptation is to move. But as a mitigation strategy, moving to safer ground “does not account for the cultural, social, and sometimes familial bonds households have with their communities,” Martín points out, “let alone the dispossession of what was likely their primary financial asset.” Further, “we know after an acute event that people want to stay as close as possible to where they were living before.” As an example of a state relocation program that works well, he pointed to New Jersey’s Blue Acres program, which moves families whose homes have repeatedly flooded to safer areas and acquires their properties as parks or community open spaces that enhances natural flood storage during extreme events. What would ease relocations away from high-risk areas everywhere, he said, is deregulation, “so that there can be a lot of building in less exposed places.”

Insurance Market Stress

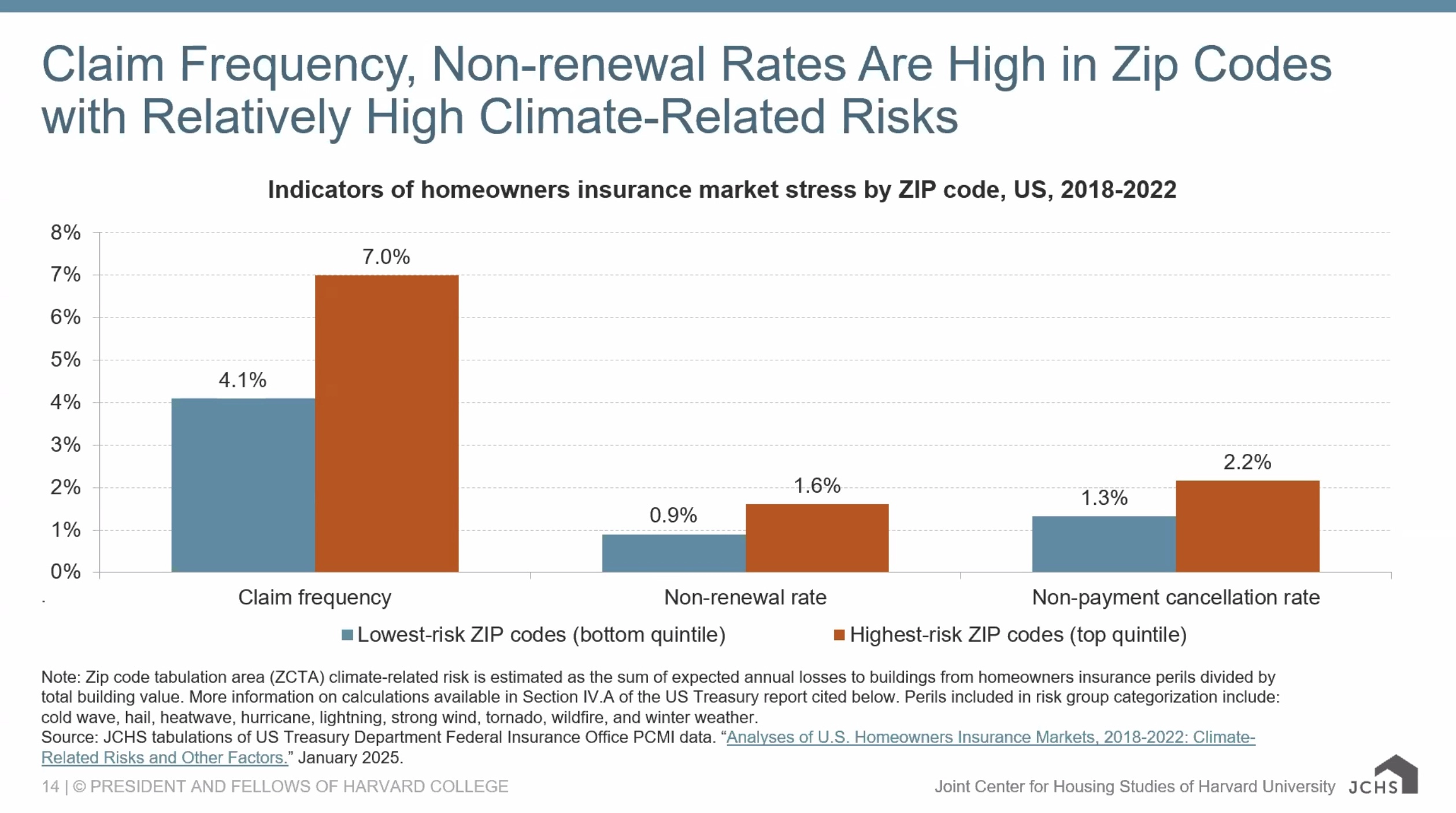

Residential property insurance is foundational to homeownership. Insurance facilitates access to mortgages, home equity lines of credit, and rental housing, and preserves the value of owners’ equity in their homes and their possessions. But about 12 percent of homeowners do not purchase homeowner’s insurance, says JCHS’s Steven Koller—what industry professionals refer to as a “protection gap.” And in high-risk areas, where premiums are already high, non-renewal rates (when an insurer drops a homeowner’s coverage) and cancellations due to non-payment of premiums are rising.

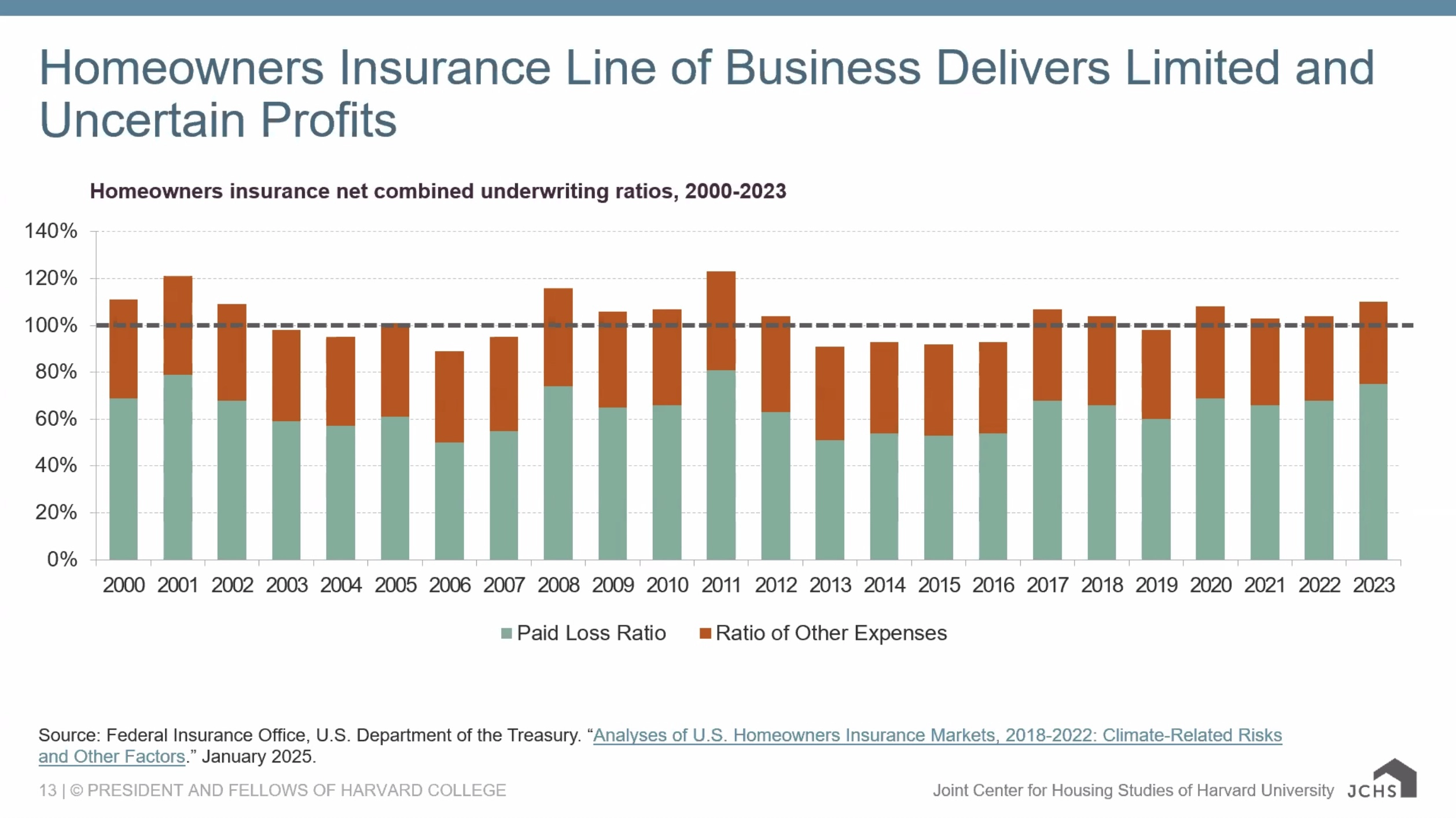

Koller began his presentation by pointing out that “rising residential insurance costs are adding to already high housing cost burdens,” for both owners and renters.” Although inflating labor and materials costs account for a substantial portion of these rising expenses, Koller noted that “we’re seeing more acute cost increases in areas with high relative climate-related peril risks.”

Insurance availability and affordability, he continued, are distinct but related challenges. “If someone is thinking about moving into a new home, they may be wondering, ‘Will private insurance be available in my area in two, 5, 10, 20 years, and if I can still get a policy, how much will it cost?’”

Insurers of Last Resort

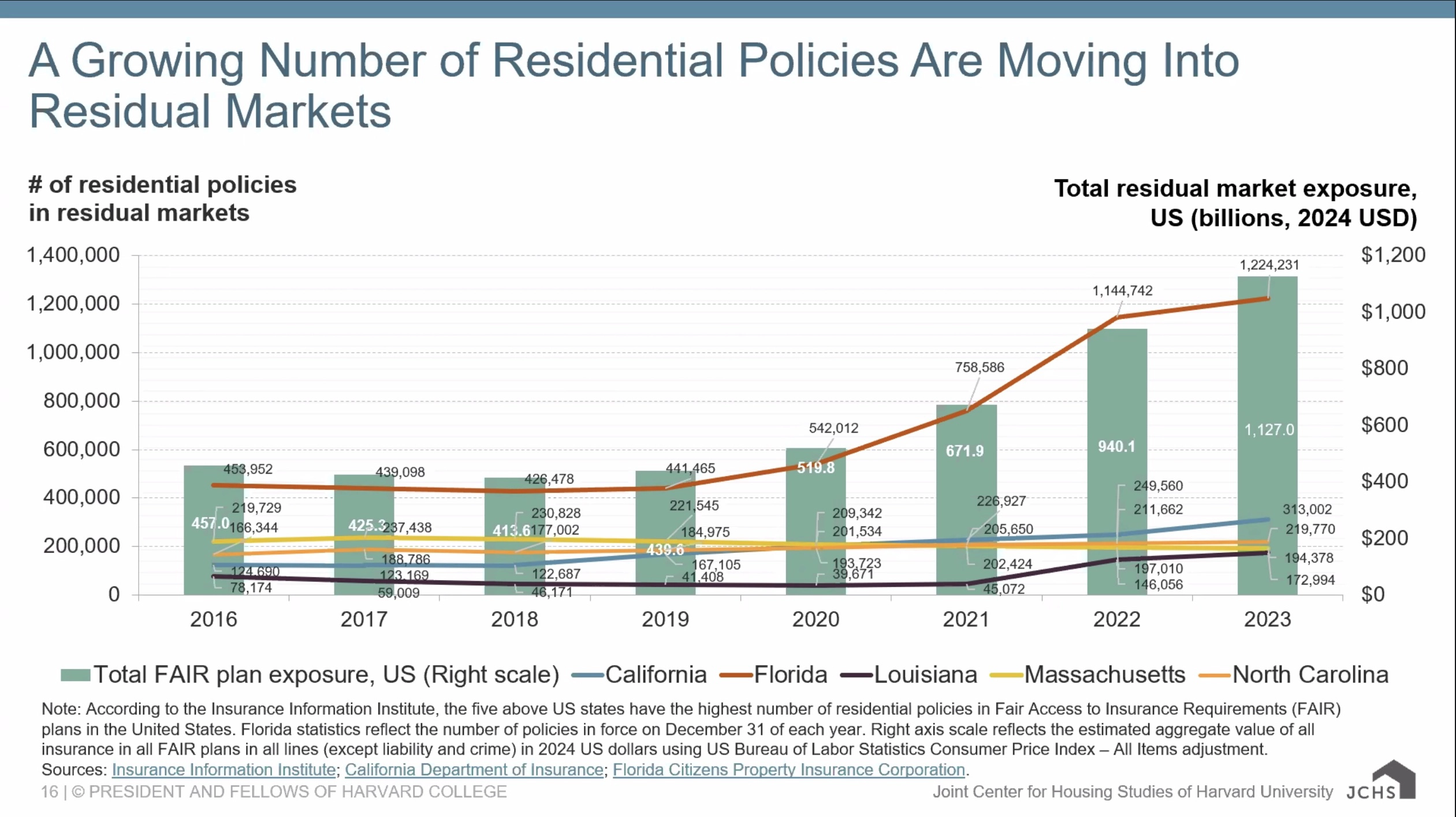

About two-thirds of U.S. states operate residual insurance markets, many of which are insurers of last resort. In Florida, where hurricanes are frequent, a government entity provides multi-peril homeowner’s insurance and single-peril insurance against wind damage to property owners who are unable to purchase coverage in the private market. Similarly, California has a state-regulated association that provides property insurance to people living in areas at high risk of hazards such as wildfires, where traditional insurers won’t provide coverage. But even these plans are under stress. After the L.A. wildfires in January 2025, for example, California’s insurance commissioner approved a $1 billion assessment on all insurers licensed to conduct property casualty business in California, to make up for the massive surge of claims. Those costs will be passed on to ratepayers statewide, even those living in low-risk areas.

States actively try to “depopulate” their residual insurance markets by moving policyholders back into the private insurance market. But for certain perils, explained Koller, that is not possible—the risks have never been conventionally insurable, and if anything, the category of such risks is expanding.

These perils, including earthquakes and floods, have been covered instead by fully public insurers. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP), for example, writes most of the residential flood insurance coverage in the country and the California Earthquake Authority covers most of the market in California. In the event FEMA incurs large losses, Congress makes them a taxpayer expense. But even as flood damages nationally are increasing, the number of flood insurance policies written has fallen. And proposed changes to both the NFIP and FEMA raise questions about the federal response to future natural disasters.

Efforts to develop sustainable, affordable, private residential insurance range from non-profits that use insurance to drive risk management, to innovation in construction materials and methods, to risk disclosure requirements than can lead to more informed housing choices. These tools won’t solve the growing cost and coverage crisis in property insurance, but they may reduce losses for homeowners and insurers. As Koller summed up, quoting Benjamin Franklin on the subject of reducing fire risk, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” Given the scale and pace of climate-change-induced threats to housing, especially as Americans have increasingly moved to risky locations, suggests that much more extensive, expensive solutions are urgently in order today.