In 1934, chemist Joseph T. Walker, Ph.D. ’33, took on the task of creating a crime-detection laboratory for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Using science in crime detection wasn’t new—Arthur Conan Doyle had envisioned it in his Sherlock Holmes mysteries, and excellent work had begun in New York City in the 1920s—but applying such skills statewide was. Yet from his first tiny lab at the State House, the 26-year-old “redhead” (as one newspaper reporter dubbed him) immediately and confidently expounded on what such a facility, if properly equipped (he needed a spectrograph), could do.

Walker’s project prospered beyond all expectations, due partly to his dogged determination, but also to the receptive environment in Massachusetts. His New York City counterparts were blocked at various turns by ill-informed or corrupt city administrators, while his lab received spacious accommodations, equipment, and supplies. He also developed a good relationship with the State Police; in 1936, he took basic training and graduated with the rank of lieutenant, thus gaining the authority to secure crime scenes.

His efforts were aided significantly by the remarkable crime-detection enthusiast and philanthropist Frances Glessner Lee, who proselytized about Massachusetts-style scientific crime detection by holding multiday seminars on the subject throughout the country. She also gave Harvard a large grant to endow a department of legal medicine, where, from 1939 onward, Walker taught courses on toxicology. In 1951, speaking in behalf of the Harvard Associates in Police Science, she told him, “No other lecturer has helped individuals and the whole training program as you have.”

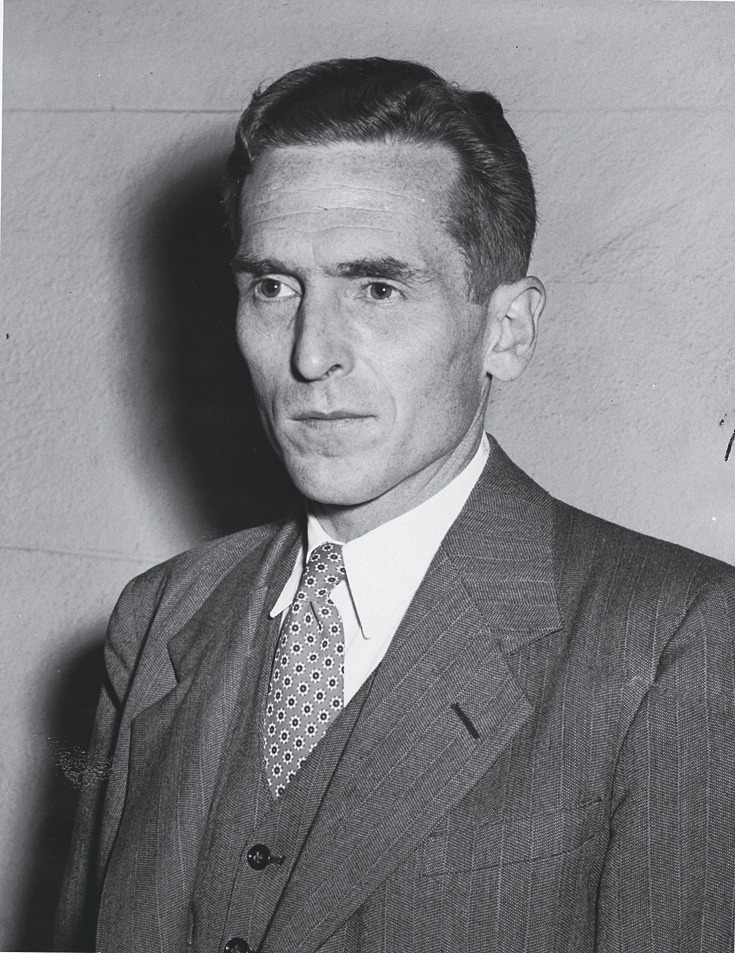

Forensic pioneer Joseph T. Walker

Photograph courtesy of the Boston Public Library

Sharing his findings brought more support. In 1937, his New England Journal of Medicine article “Chemistry and Legal Medicine” cited the assertion, by the American Medical Association’s Committee on Medicolegal Problems, that each state should have a crime lab; he then listed ways to use chemistry in crime detection, including his new method to determine shooting distances “through the location of each individual grain of powder” on victims’ clothes. Future articles explored such topics as “Bullet Holes and Chemical Residues in Shooting Cases,” “Visualizing of Writing on Charred Paper,” “The Spectrograph as an Aid in Criminal Investigation,” “The Quantitative Estimation of Barbiturates in Blood by Ultraviolet Spectrophotometry,” and “Paper Chromatography in Criminal Investigation.”

But what gained the greatest respect for Walker’s field was the actual work his laboratory performed, especially in a number of spectacular cases. The “Case of the Merry Widow,” which drew prolonged international attention, concerned the 1936 murder and dismemberment of socialite Grayce Asquith. Solving the murder involved identification of blood type (from the contents of a clogged bathtub drain) and the first-ever use of a toe print (left in blood under the tub) in a criminal trial. That case was fairly simple; others were not. In 1945, a prominent lawyer was convicted of electrocuting an infant son born with Down syndrome after Walker proved that only deliberate action by the father could account for the presence of microscopic quantities of copper from an electric cord on both the infant’s body and a metal tray.

Other states sought to benefit from Walker’s expertise. As late as 1950, though already ill with Hodgkin’s disease—probably the result of inhaling benzene fumes in his own laboratory—he traveled to Maine to teach 25 state policemen about forensic science and to give evidence at the retrial of a deputy sheriff convicted of murder in 1938. Walker testified that the man’s gun—allegedly the weapon used in a very bloody bludgeoning—had, in fact, tested negative for even minute quantities of blood; the deputy was subsequently released on the grounds that he had been fraudulently convicted.

The energy, and the eagerness to invent and improve, that Walker brought to his work characterized him off the job as well. In the 1940s, he aided the war effort by cultivating large “victory gardens” and, like others with home metal lathes, making precision parts for Allied bombers. Realizing that the pH of the birth canal is critical in conception, he devised a simple chemical remedy that enabled his wife and several friends to have children—and, when his toddler son accidentally consumed arsenic by licking ant bait, he saved the child’s life by insisting that the hospital administer an untried chemical remedy that harmlessly sequestered the poison. Just before his death, he was working on a device to vacuum-dry foodstuffs and participating in the effort to launch WGBH—one of the first public-television stations in the country.

When he died, his last words were “People are wonderful”—strange, perhaps, considering the nature of his work, but understandable given the support and enriching professional friendships he had enjoyed. (Lawyer-turned-mystery-writer Erle Stanley Gardner called him “the greatest real-life detective” he had known.) In his 18-year career, Walker had clearly established the importance of scientific crime detection, and many more states had or would soon have modern crime laboratories. An obituary in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology stated: “Throughout the world his methods are used, his name is known, and all men benefit.” An honor guard of police troopers from all six New England states and New York stood erect throughout his funeral service. The short, very driven, “redhead” had done a lot of living in a mere 44 years.