In the fall of 2002, in those war-darkened days when Seamus Heaney was still among us at Harvard (then as Emerson Poet in Residence), he generously agreed to come to a session of my freshman seminar on poetic translation. For two hours he joined in discussions of the Horace translations by some of the 12 entranced 18-year olds, some now published poets and writers. He also talked about his own Horatian translation, of Odes 1.34, written the year before in response to the terror attacks of September 11, 2001. The poem concerns life’s unpredictability, in the metaphor of Jupiter’s lightning striking in a clear sky. At the time of the seminar, Heaney was still living with the poem, first published as “Jupiter and the Thunder” in The Irish Times of November 17 of that year. He would continue to do so until it was published as “Anything Can Happen, after Horace Odes 1.34”in District and Circle (2006), with Horace made new: “Anything can happen, the tallest towers | Be overturned.”

Since that visit, fully five verse translations of the entire Aeneid, the Roman epic of Horace’s contemporary Virgil, have appeared: by Stanley Lombardo (2004), Robert Fagles (2006), Frederick Ahl (2007), Sarah Ruden (2008, the first by a woman), and Barry Powell (2016). In 2011, A.T. Reyes published C.S. Lewis’s Lost Aeneid (book 1 and most of book 2, in rhymed alexandrines). Each has its appeal, each its adherents. Let a thousand Aeneids bloom, I say, for to read the poem in the Englished versions of some of our age’s best poets is to be doubly enriched. There has been no comparable period in the 600 years since the first English (Middle Scots, actually) translation by Gavin Douglas, written in 1523, published in 1553. Others followed until Dryden’s great Aeneis of 1697 silenced translators throughout the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth. (Wordsworth started a version and got through most of book 3, before abandoning it.)

Into this abundant stream steps Seamus Heaney with the posthumous Aeneid Book VI, marked “final” in his hand a month before he died. In fact, Heaney had been in this stream for some time. As he put it in Stepping Stones (Dennis O’Driscoll’s series of interviews with the poet):

[T]here’s one Virgilian journey that has indeed been a constant presence, and that is Aeneas’s venture into the underworld. The motifs in Book VI have been in my head for years—the golden bough, Charon’s barge, the quest to meet the shade of the father.

By then he had already begun the translation, “in 2007, as a result of a sequence of poems written to greet the birth of a first granddaughter,” he writes in the Translator’s Note that leads off this new volume. It is also “the result of a lifelong desire to honour the memory of my Latin teacher,” Father Michael McGlinchey, with whom he read Aeneid IX at St. Columb’s College in County Derry. He recalls McGlinchey’s “sighing, ‘Och boys, I wish it were Book VI.’”

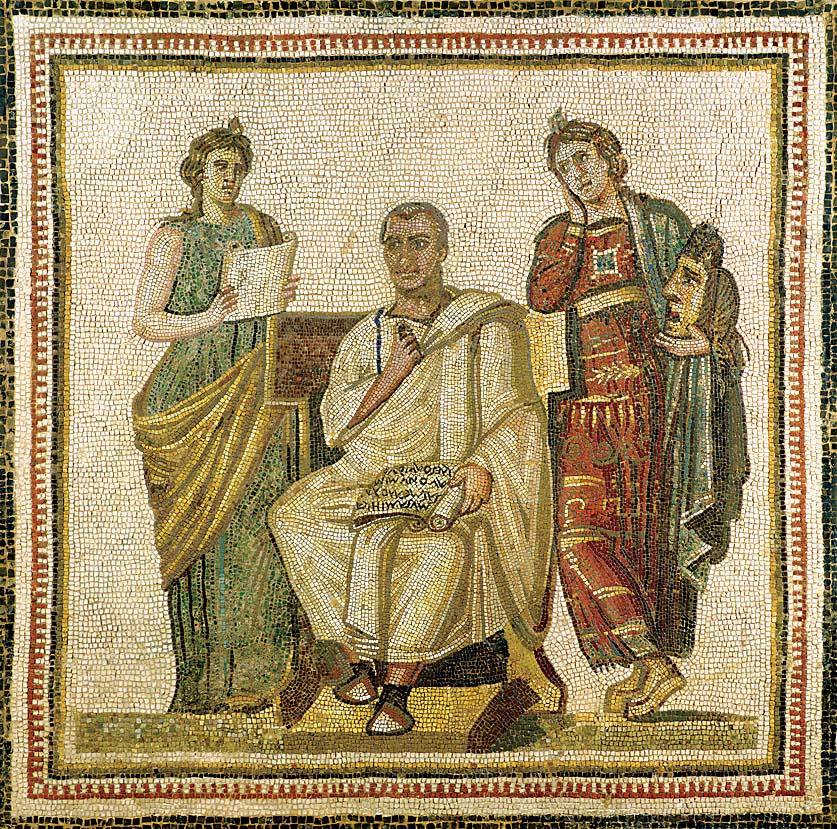

Virgil (70-19 b.c.e.) sits between Clio, the Muse of history, and Melpomene, the Muse of tragedy, in this third-century mosaic from a site at Sousse, Tunisia.

Musee National du Bardo, Le Bardo, Tunisia / Bridgeman Images

Even earlier, in 1991, “The Golden Bough,” a translation of Aeneid 6.124–48, came out as the first poem in Seeing Things. Twenty years later, “Album” (also in 2010’s The Human Chain) fondly recalled three separate embraces of the father dead since 1986, culminating in a simile “just as a moment back a son’s three tries | At an embrace in Elysium”—a clear invocation, in words full of their own literary memories, of Aeneas as the hero tries and fails to embrace the shade of his own father. The 12 sections of “Route 110” (in The Human Chain) “plotted incidents from my own life against certain well-known episodes in Book VI” (vii–viii), by way of the bus route from Belfast to Heaney’s home in County Derry. In “Route 110,” the poet buys a “used copy of Aeneid VI,” then takes the bus ride home, reading of Lake Avernus and “Virgil’s happy shades” to the sound of “Slim Whitman’s wavering tenor.”

Lingering Where It Matters

Aeneid VI starts with the hero’s making landfall at Cumae, the northern point of the Bay of Naples. There the Trojan exile meets the Sibyl, prophetess of Apollo, who guides him down into the Underworld, directs him to the golden bough that will give him access, and joins him on his ghostly journey: encounters with Charon’s ferry of the dead, the hellhound Cerberus, Trojan comrades and Greek foes fallen in the war at Troy, the shade of Dido who died for love of him, and finally to the desired meeting with his father, Anchises (replacing the mother visited by Homer’s Odysseus).

The lines of “The Golden Bough” from 1991, now iambic pentameter like the whole book, have been tightened and trimmed, overhauled and reordered in a process revealed at the end of the preface:

rhythm and metre and lineation, the voice and its pacing, the need for a diction decorous enough for Virgil but not so antique as to sound out of tune with a more contemporary idiom—all the fleeting, fitful anxieties that afflict the literary translator.

Virgil’s language is not ornate: “neither overblown nor understated,” as a Roman contemporary put it. All great poetry is modern, that is, readable in the modernity of its idiom—whatever the occasional recourse to high style, to archaism, to technical language, to neologism. The job of the translator is to create poetry out of poetry, idiom out of idiom, and Heaney has done that job superbly, capturing the energy of the original, emptying the word-hoard with narrative, description, and character speech brilliantly represented and renewed, always in tune with the varying emotional registers of this, the most pathetic of the Aeneid’s books. Rare is the translation that brings over into true poetry, as this one does, the words, the tone, the music of the original.

Seamus Heaney

Photograph by David Levenson/Getty Images

Heaney’s 1,222 lines convey the entirety of Virgil’s 908, printed on facing pages—clearly important for Heaney. The morphological and syntactical compression of Latin, relative to English, make this just about right (Dryden needed 1247 lines, Mandelbaum, 1203). Heaney, like them unconstrained by the Latin line, can linger where lingering matters, as when Aeneas looks his last at the unresponsive shade of Dido, in a single, packed line of Latin that here becomes almost two: “gazes into the distance after her | Gazes through tears, and pities her as she goes.” The expansion by repetition draws attention as well to Virgil’s striking use of the verb prosequor, here used in Latin for the first time to mean “follow after with the eyes.” Elsewhere, memory of a son’s fall, through failure of a father’s art, leads to a second failure of art, and the falling of the artist’s hands: “Twice | Dedalus tried to model your fall in gold, twice | His hands, the hands of a father, failed him.” The consecutive lines of Virgil begin with bis (“twice”), a word effectively moved to line-end in the English. In the Latin, Virgil’s description ends mid-line, mirroring the unfinished artwork, but the translation needs two full English lines. Virgil in three words gets the horror of the father trying and failing to depict the death of the son: patriae cecidere manus. He does so by placing the adjective (“belonging to a father”), which in Latin can have the force of a noun, in the emphatic first position. Heaney gets the same effect in nine words, by doubling “hands” (manus), supplying the noun (“of a father”), with the indefinite article universalizing the catastrophe. “Fall” and “failed”—cognates in Latin as well (casu….cecidere)—get to the heart of the noun and verb. This sort of exercise could be repeated over and over again throughout the translation. Or just read it, and know you are close to the poet with whom Heaney was living these last years.

English, in Touch with Metaphor

English for the most part has lost touch with the metaphor in its (frequently Latin) etymology, but Heaney’s English nestles up to those origins, again keeping a version of the Latin in his words. He clearly cares about the language and about his representation of it. The body of a dead comrade “Lies emptied of life” (iacet exanimum, literally, “breath gone out of it”); the cave to the Underworld is “A deep rough-walled cleft, stone jaws agape” (hiatu, often with the meaning bodily gape, yawn). Down below we meet various personified evils, including “Death too, and sleep, | The brother of death,” as always eschewing the Latinate (consanguineus) with the Anglo-Saxon “brother” underscoring the metaphor. And where Heaney finds pure metaphor, he translates that, too, as in Virgil’s “rowing with wings” for Daedalus, or his “prows frill the beach” for the Trojan ships on the shore of Italy.

Among many vivid descriptive passages are the lines on Charon, the ferryman dear to Heaney, as to Dante, Dryden, and Delacroix, among many others:

And beside these flowing streams and flooded wastes

A ferryman keeps watch, surly, filthy and bedraggled

Charon. His chin is bearded with unclean white shag;

The eyes stand in his head and glow; a grimy cloak

Flaps out from a knot tied at the shoulder.

All by himself he poles the boat, hoists sail

And ferries dead souls in his rusted craft

Old but still a god, and a god in old age

Is green and hardy.

Not a single Latinate word, as the vitality and squalor come fully across. Later Charon delivers his unwonted mortal cargo to the further shore,

Under that weight the boat’s plied timbers groan

And thick marsh water oozes through the leaks,

But in the end it is a safe crossing, and he lands

Soldier and soothsayer on slithery mud, knee-deep

In grey-green sedge.

Every word has an analogue in Virgil’s Latin, but the voice is that of Heaney. The sounds of Hell are well represented, as in the punishment of Salmoneus for imitating Jupiter in his thunder cart with “the batter of bronze and the clatter | Of horses’ hooves,” the alliteration responding to and extending that of Virgil (cornipedum pulsu). Or in the noise of the Fury Tisiphone’s torturing sinners: “Sounds of groaning could be heard inside, the savage | Application of the lash, the fling and scringe and drag | Of iron chains.” Or “a grinding scrunch and screech | Of hinges as the dread doors open.”

Some critics, chiefly Anglo-Saxonists, found fault with the Hiberno-Englishisms of Heaney’s translation of Beowulf, as indicating inept appropriation. But others rightly saw it as an act of stealing in the best sense, transforming “the song of suffering that is Beowulf into a keen for his own people’s troubles,” (as Thomas McGuire wrote in New Hibernia Review). The much reduced use of such language in Aeneid Book VI confirms this more creative view of the matter. Not that Virgil cannot be treated that way at times, as with “scringe” (“scratching sound”) above. In fact the practice of domesticating into Hibernian—never intrusive, but unmistakable—continues that found in Heaney’s translation and adaptation of Virgil’s pastoral eclogues in Electric Light, from 2001: “Bann Valley Eclogue,” where the Virgilian golden age is thoroughly Irish: “Cows are let out. They’re sluicing the milk-house floor”; or the translation, “Virgil: Eclogue IX,” where a bull is “The boyo with the horns,” while the older shepherd says, “That’s enough of that, my boy. We’ve a job to do.” Virgilian pastoral and Irish poetry are akin, both close to the soil, in Heaney as in Patrick Kavanaugh and John Montague.

At Home in Ireland

So it is that this Aeneid can feel at home in Ireland: “fell like a dead man | On a heap of their slobbered corpses” for confusae (“jumbled”)—perhaps recalling the “warm thick slobber | of frogspawn” from “Death of a Naturalist”; “nor bury in home ground”; “in the very lowest sump”; of Silvius, “the lad you see there.” Heaney’s Aeneas, at the funeral of his captain Misenus, even takes on the look of Father McGlinchey, “asperging men lightly | From an olive branch.” This all works because we want to hear Heaney along with Virgil. Does he go too far when the Sibyl, to subdue Cerberus, “flings him a dumpling of soporific honey | And heavily drugged grain”? I think not. It is worth it to think of our poet smiling at that line, even in the Underworld.

In a fragment of an Afterword, Heaney called it “the best of books and the worst of books.” Best because of “the pathos of the many encounters it allows the living Aeneas with his familiar dead.” Worst “because of its imperial certitude, its celebration of Rome’s manifest destiny, and the catalogue of Roman heroes…,” down to the man under whose new monarchy Virgil would find himself: the “last of the war-lords,” as Augustus has been called. Though these lines— Anchises’s, not Virgil’s own—are not without pathos, and resist being called encomium, Heaney here thought the translator’s task “is likely to have moved from inspiration to grim determination,” as his preface puts it. Not that his translation fails them in any way. But his heart is elsewhere, as was Virgil’s, in Aeneas’s encounters with dead comrades and his dead lover Dido, in the reunion with his father and the embrace that cannot happen, and in the loss, memory, and consolation that come through the music of these scenes. The poets are also in Elysium, an inviting spot as the legendary Musaeus describes it in Heaney’s evocative verse:

None of us has one definite home place.

We haunt the shadowy woods, bed down on riverbanks,

On meadowland in earshot of running streams.

It is not hard to imagine Seamus Heaney, who spent so much time with Virgil in this world, now reunited in the next, haunting such woods with the Roman poet, as they do in this breathtaking new translation.