Wildlife artist Barry Van Dusen spent nearly two years traveling to all 57 Mass Audubon public sanctuaries to capture (on paper) New England’s flora, landscapes, animals, and birds. Birds are particularly tricky work. Rendering feathers demands finesse. No pigment yet captures true iridescence. And the subjects rarely sit still.

At the Daniel Webster Sanctuary in Marshfield, Van Dusen set up his stool, art supplies, and binoculars beside a swath of wetlands, and was lucky enough to watch a Virginia rail and her chick. The secretive, long-toed birds dwell deep in the cattails, but here “wandered around together in the open and picked at a pollywog,” he reports, enabling him to produce a watercolor of the pair. It’s on display, along with about 50 more of his sanctuary works, at the Museum of American Bird Art at Mass Audubon, in Canton, Massachusetts, from May 21 through September 17.

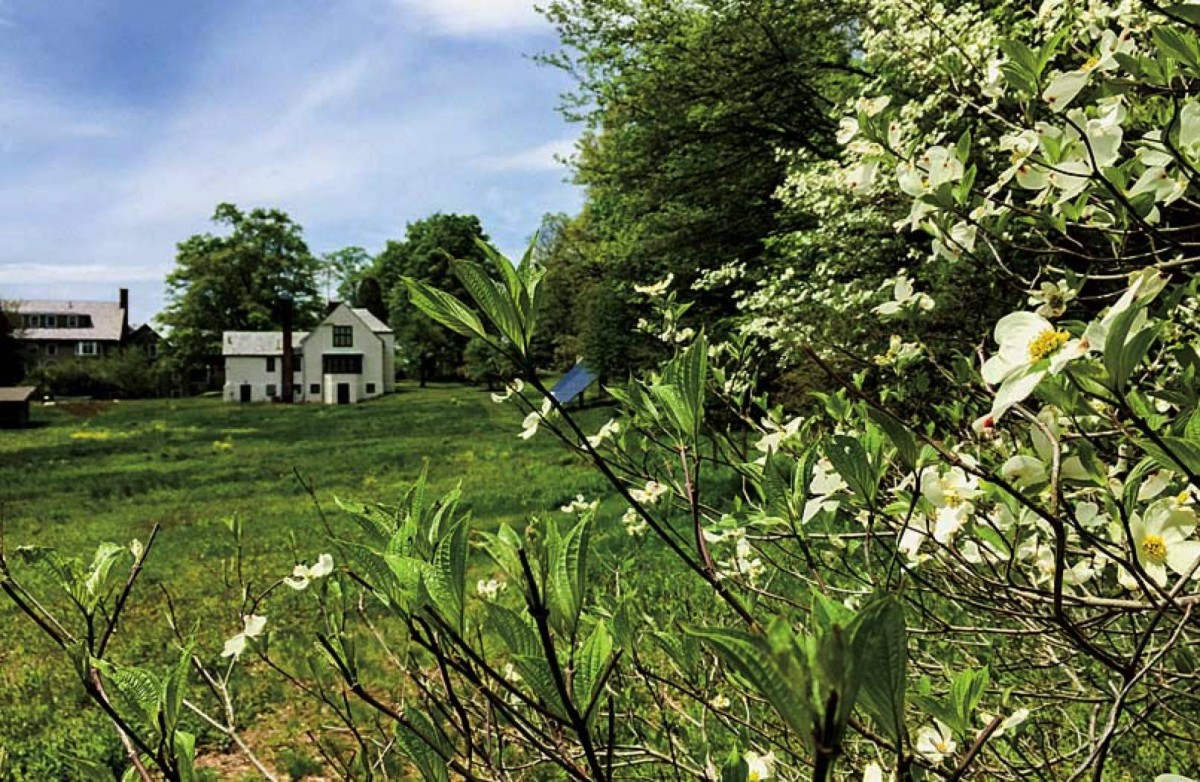

The Museum of American Bird Art

Courtesy of the Museum of American Bird Art

The small, unusual museum (Van Dusen is artist-in-residence) is housed in the studio of a pioneering natural-history filmmaker and birder named Mildred Morse Allen. She bequeathed her estate to Mass Audubon in 1989, along with the surrounding 121 rural acres, which are also open to the public. Woodland trails snake along pine and oak groves, vernal pools, and Pequit Brook—prime wildlife-watching territory. This spring, listen for wood frogs and singing birds like Baltimore orioles, scarlet tanagers, and wood warblers. In May, hunt for pink lady’s slipper orchids, and by July clusters of cardinal flower in and around the brook are hummingbird haunts.

To receive curated picks of what to eat, experience, and explore in and around Cambridge from the editors of Harvard Magazine follow Harvard Squared.

To receive curated picks of what to eat, experience, and explore in and around Cambridge from the editors of Harvard Magazine follow Harvard Squared.

The Canton museum, says director Amy T. Montague, is the “only one in the world focused on American art inspired by birds.” It opened in 1999, but its art collection began growing almost as soon as Mass Audubon was founded nearly a century earlier. There are thousands of works—from engravings by John James Audubon himself to Pop Art silkscreen prints of a bald eagle and Pine Barrens tree frog (donated by their creator, Andy Warhol) to the exquisite carved decoys, coveted by collectors, of Anthony Elmer Crowell. The Cape Codder built his career as a gunning guide, then as a craftsman, through a group of Harvard sportsmen, including noted conservationist and public servant John C. Phillips, B.S. 1899, M.D. 1904. “The connections between Harvard and the early American conservation movement are strong, and most of the gunners were early conservationists,” Montague explains.

Bobolinks painted at Drumlin Farm

Courtesy of Barry Van Dusen

Mass Audubon was co-founded by another Canton resident, Harriet Lawrence Hemenway. An independent spirit (she donated a separate Hemenway Gymnasium to Radcliffe after her husband, public servant and philanthropist Augustus Hemenway, A.B. 1875, donated the first Hemenway Gymnasium to Harvard), she was appalled by the slaughter of birds to feather fine ladies’ hats so she drafted a group of like-minded, influential women and men to help protect wild birds. “Museum visitors have been surprised to see shorebird decoys,” Montague says, “because it’s hard for us today to imagine…plovers, red knots, and dowitchers as delicacies for diners. [But] market gunning was a lucrative enterprise, and huge quantities of these birds were shipped from the shore to restaurants in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. This practice was ended through the efforts of Mass Audubon and other early conservation activists with the passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918.” The art museum, Montague adds, thus tells the “stories of the changing relationships between humans and the natural world over the centuries.”

Also at the museum through May 14 is “Birdscapes: Recent Oil Paintings by James Coe,” class of ’79. Coe studied biology at Harvard before going to art school, then worked for more than 15 years as a field-guide bird illustrator. He now paints primarily rural landscapes—and often the birds living within them—in and around the Hudson Valley, where he lives.

A day trip to the museum could include stops at Mass Audubon’s oldest and largest preserve, the Moose Hill Wildlife Sanctuary (five miles away), and the nearby Eleanor Cabot Bradley Estate, a sprawling brick country home with formal gardens, owned by The Trustees of Reservations, where seasonal concerts and events are also planned. For lunch in Canton, try the Amber Road Café or sushi at Takara, or head to nearby North Easton, for a more elaborate meal at The Farmer’s Daughter.