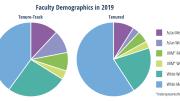

Harvard’s faculty ranks have, gradually, become increasingly diverse. The intersection of lifetime tenured appointments; no mandatory retirement age; a decade of very constrained growth; and the long time it takes students to progress from studying a discipline through completing doctoral work and proceeding into academia necessarily combine to make the pace of change evolutionary, not revolutionary. But comparing the census totals from late in the presidencies of Lawrence H. Summers (which ended in 2006) and Drew Gilpin Faust (2018) provides clarity. In the fall of 2006, the Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS, the largest Harvard faculty) had 702 tenured and tenure-track members, of whom 172 were women and 116 minorities; in the fall of 2017, of 738 members, 222 were women (an increase from 24.5 percent to 30.0 percent) and 162 minorities (from 16.5 percent to 22.0 percent).

The data come from the annual report of the office of faculty development and diversity; its director, senior vice provost Judith D. Singer, points to an accelerating pace of change. Across the University, from calendar year 2006 through last year (when there were about 1,100 tenured professors), 582 offers of tenure were accepted—half by women and/or minorities, and 39 percent by women and/or members of underrepresented minorities. Of the 170 tenured appointments made during the latest four calendar years (2015 through 2018), 57 percent were women and/or minorities, and 45 percent women and/or underrepresented minorities.

Singer points to varying indicators to explain the change in the faculties’ composition. During those four latest years, 61 percent of the tenured appointments were internal promotions. Harvard’s schools have, during the past decade plus, adopted a tenure-track system: bringing a cohort of junior faculty members to campus to be mentored, offered opportunities to develop, and then be considered for promotion. That system favors recruiting young scholars, who tend to be more diverse, reflecting today’s more diverse university enrollments. (Past Harvard practice expected junior faculty members to leave after several years, and made tenured appointments only at the senior, full professor level—a less diverse cohort, given prior decades’ academic population.)

Of course who is recruited matters, at any level of appointment. Among the underrepresented minorities (Hispanic, black, and Native American) who accepted tenured appointments from 2006 through 2018, more than half were from outside the University, Singer says, indicating that the searches succeeded in identifying a diverse pool of candidates.

It has taken real, sustained effort to achieve these results, she says, given the strongly competitive market for faculty among a few dozen leading research universities for the best candidates in any given discipline.

Harvard’s tenured faculty ranks have grown at a compound annual rate of slightly more than 1 percent since the middle of the previous decade (Singer calls it a “period of incredible stasis”), reflecting tepid endowment returns and the pressure on budgets imposed since the 2007-2008 financial crisis and recession. The most robust growth has been concentrated in engineering and applied sciences (which became a school in the fall of 2007, and has ridden the flood tide of interest in computer sciences and allied fields)—disciplines historically lacking in women and underrepresented minorities. As a result, much of the aggregate diversification of the University’s faculties has been effected by filling vacancies arising from retirements and departures for other institutions. Increasingly, of course, those positions are filled by promotions from within.

Much of the change dates to the end of the Summers administration, when the president’s controversial remarks on women in the quantitative disciplines resulted in his appointment of task forces on women faculty and women in science and engineering, both overseen by Faust, then Radcliffe Institute dean. Their reports, in May 2005 (see “Engineering Equity,” July-August 2005, page 55), “made faculty diversity a priority at the University,” Singer says—and resulted in the creation of the office she now runs. Faust’s appointment as Harvard’s first female president, in 2007, embodied the issue in the institution’s leadership.

Deans, department chairs, and search committees came to ensure that candidate pools reflect the breadth of possible applicants.

In ensuing years, the adoption of a tenure track (partly a response to peer practices putting Harvard at a disadvantage in recruiting younger scholars) pushed search committees toward new kinds of candidate pools. The culture changed, too, Singer stresses. Senior faculty members took to retirement incentives (offered during the financial crisis, and then standardized) and also paid more attention to intellectual renewal of their fields. Deans, department chairs, and search committees internalized the value of ensuring that candidate pools reflect the breadth of possible applicants. And as critical masses of formerly underrepresented professors arose, other candidates became more comfortable with the idea that Harvard could be a good place for them, too. “It’s a long process,” Singer allows.

Tangible interventions have helped. Summers committed $50 million of central funds to further diversity, and Faust added $10 million when the inclusion task force she appointed reported last year. Faculties and deans decide what appointments to make and how to pay for them—but Singer says that these supplemental funds have been invaluable in dozens of cases in closing deals that attract or retain scholars whose work requires expensive investments for space (refitting buildings, equipping laboratories), or for research support, summer salaries, or transitional housing. It’s a “hot market,” she sums up, with competing institutions in “a bit of an arms race.”

Harvard has also invested tens of millions of dollars in renovating and augmenting its childcare facilities, and, beginning in 2009, offering childcare scholarships (the latter totaling more than $10 million in the decade since). For the past two years, Singer reports, all eligible faculty members who applied for an open slot in a campus facility were offered at least one. And although Harvard does not create jobs for spouses or partners as part of recruiting, it provides meaningful assistance in such situations; Singer says she and her team regularly work with faculty partners and spouses, engaging peers at other area institutions to look for leads, pass on CVs, and broker important introductions.

The diversity processes are still not frictionless. At the February FAS faculty meeting, Robinson professor of mathematics Wilfried Schmid asked dean Claudine Gay why that department’s current search, for two prospective appointments, announced by advertising soliciting applicants broadly, had been conducted by a search committee, rather than by the department as a whole—and why administrators had monitored the process ex officio, through the dean of science’s office. (Mathematics talent has been understood to develop rapidly, on a different trajectory than in other disciplines; the department has typically operated without a tenure track, and has therefore made its appointments idiosyncratically compared to the new norm. It has, in its history, appointed just two women to tenured professorships, of whom one remains at Harvard.) Gay responded levelly that this was the first departmental search conducted in full accord with FAS policies; that there could naturally be “confusion” and “growing pains” associated with following such procedures; and that the participants might have to “struggle” to come to terms with them.

Gay is herself a representative of a new generation of academic leaders, whose presence broadens the understanding of what a Harvard scholar can be: she is one of four African-American women deans. Their presence, Singer notes, embodies the value the University’s places on searching for talent everywhere—and ensuring that that value is made manifest in appointing the next generation of professors.

Looking ahead, she sees a new kind of challenge emerging, for all Harvard faculty members, driven by “the dramatic shift” in student interest toward computer science, applied math, statistics, and related fields, “in numbers we can barely cope with” currently as far as staffing classrooms with suitable faculty. Harvard and a few dozen other major universities, she continues, create the faculties of the future, but many undergraduates in these fields are attracted to richly compensated positions in business and finance. “Are people drawn to taking that skill set and going into markets,” she asks, “or are they drawn to the life of a faculty member”—with rewards including the degree of autonomy involved, the pleasure associated with the life of the mind, and the renewing chance to work with young learners. In a word, Singer says, professors have an opportunity and obligation to convey, alongside their knowledge, the reality that their work can be so fulfilling, and sufficiently supported, that it is “fun, 24/7.”