In late February, some 10 months after the University announced its 2050 “net-zero” goal for greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions associated with investments held in the endowment, Harvard Management Company (HMC) issued its first “Climate Report.” The document detailed initial progress in the multiyear process of determining how to get data about GHG emissions produced by companies in which the endowment is invested and ways to determine the “carbon footprint” of its investments overall. And as an important aside, it made an initial, limited disclosure about fossil-fuel holdings—a point of particular interest to student, faculty, and alumni advocates of divesting such assets (which the University declines to do).

On that matter, HMC reported that as of last June 30, the end of fiscal year 2020, it had “no direct exposure to companies that explore for or develop further reserves of fossil fuels.” At the end of fiscal 2008, when HMC was a much different organization pursuing much different strategies, at least 11 percent of the portfolio (approximately $4.1 billion) was invested in fossil-fuel commodities or enterprises. Including indirect exposure (assets held by external investment managers, as most HMC investments are today), the level of fossil-fuel-related investments at the end of fiscal 2020 was “less than 2 percent”: about $800 million.

The broader objective—a portfolio that in the aggregate emits no GHGs by 2050—depends on both changes in the economy and public policy (company and consumer shifts to clean sources of power) and on new techniques for collecting data from enterprises in which HMC might invest and its holdings as a whole. The data required include portfolio enterprises’ baseline GHG emissions, what steps they are taking to get to net-zero emissions, and how investors harness that information in assembling their holdings.

As HMC points out, it no longer manages investments directly, so it needs new ways to get information on the underlying assets from the external fund managers it retains to put Harvard’s cash to work. Moreover, even as data become more available from large, publicly held corporations, HMC is heavily oriented toward private-equity investments (where climate-risk assessments and emissions data are less well developed) and hedge funds (which may involve “long/short equity funds, high-frequency trading, the use of complex derivatives, and shorting of securities,” all of which complicate the data-gathering problems considerably). In the near term, HMC is subscribing to external data providers, and working with other institutional investors to expand the availability of climate information, portfolio-assessment techniques, and so on. Clearly, much of the work is nascent—think of this an as R&D operation—in part reflecting the primitive state of needed reporting and analysis at the level of companies in which HMC might invest. For a more detailed report, including information on some of HMC’s metrics, see harvardmag.com/hmc-fossilfuel-net0update-21.

Advocates, meanwhile, remain committed to overturning Harvard’s divestment stance. Divest Harvard acknowledged “steps in the right direction” in the HMC report, but blasted “Harvard’s failure to commit to fully divesting and reinvesting its fossil-fuel holdings” despite “repeatedly acknowledg[ing] the ‘urgent’ need for ‘immediate’ action on climate change….”

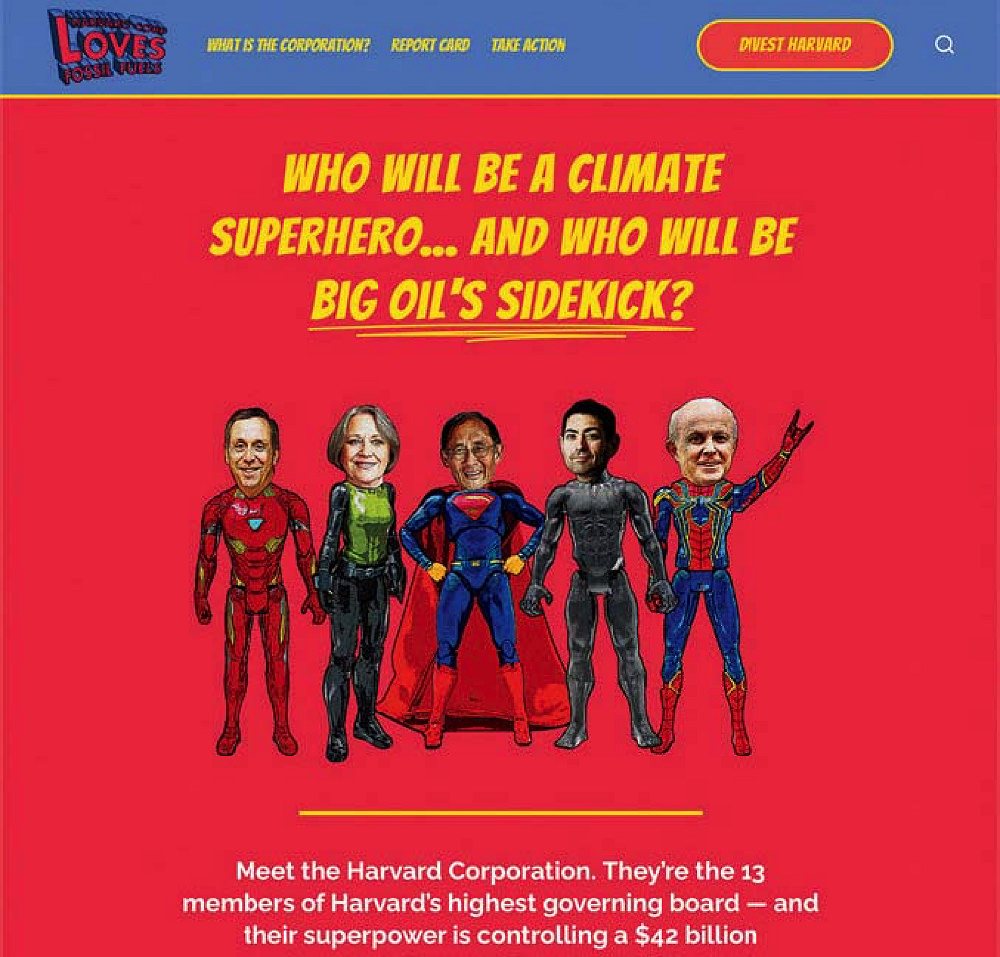

The University’s academic approach, and the divestment advocates’ campaign, played out in a revealing way days before the HMC report. The newly redesigned Harvard homepage (www.harvard.edu), which features themes for a week or two at a time, debuted a climate-change focus in mid February. And Divest Harvard published a mock superheroes comic book purporting to explain how the Corporation (the ultimate decisionmaker) works and depicting its members as commanding “superpowers” but choosing to be “missing in action” on climate: “Will they let the bad guys win? Or will they step up and be the heroes the planet needs?”

Those dramatics aside, balloting in the annual election for members of the Board of Overseers began April 1. As reported, three candidates campaigning on the Harvard Forward platform, which includes divestment, have qualified for the ballot by petition, raising the salience of the issue for alumni for the second year in a row. (Read all the candidates’ perspectives at harvardmag.com/overseer-nomineeviews-21.)

Elsewhere, diverse schools continue toward phasing out or divesting fossil-fuel holdings. The University of Southern Californiaannounced in February that it would liquidate its remaining fossil-fuel assets and avoid new ones. Tufts has opted for a more limited process, ruling out direct investments in companies that produce coal or tar sands (it has none now). It will also invest $10 million to $25 million in enterprises and funds meant to have a “positive impact” on climate change. And Rutgers revealed on March 9 that it would divest—ceasing new investments in fossil fuels, exiting index funds with such investments within a year, and winding up related private investments within a decade; 5 percent of its $1.6-billion endowment is affected.

Separately, Yale announced in early March that FedEx (founded and chaired by its alumnus Frederick W. Smith) had donated $100 million to fund a new Center for Natural Carbon Capture—part of a larger, campus-wide Planetary Solutions Project on climate change and biodiversity. FedEx itself is beginning to acquire thousands of electric delivery vans. That sort of improvement in the ways the world conducts its business, and related academic research on large-scale solutions, suggest the directions that Harvard, its endowment, and peer institutions must follow to address the threats of planetary climate change.