Though snap judgments get no respect, they are not so much a bad habit as a fact of life. Our first impressions register far too quickly for any nuanced weighing of data: “Within less than a second, using facial features, people make what are called ‘spontaneous trait inferences,’” says Amy Cuddy.

Social psychologist Cuddy, an assistant professor of business administration, investigates how people perceive and categorize others. Warmth and competence, she finds, are the two critical variables. They account for about 80 percent of our overall evaluations of people (i.e., Do you feel good or bad about this person?), and shape our emotions and behaviors toward them. Her warmth/competence analysis illuminates why we hire Kurt instead of Kyra, how students choose study partners, who gets targeted for sexual harassment, and how the “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood bonus” exert their biases in the workplace. It even suggests why we admire, envy, or disparage certain social groups, elect politicians, or target minorities for genocide.

Cuddy also studies nonverbal behavior like the postures of dominance and power. Intriguingly, her latest research connects such poses to the endocrine system, showing the links between stances, gestures, and hormones. This work may help clarify how men and women rise to the top--or fall by the wayside--in school and at work. And it relates to some surprising findings about how venture capitalists decide where to make their high-risk investments.

Quite literally by accident, Cuddy became a psychologist. In high school and in college at the University of Colorado at Boulder, she was a serious ballet dancer who worked as a roller-skating waitress at the celebrated L.A. Diner. But one night, she was riding in a car whose driver fell asleep at 4:00 a.m. while doing 90 miles per hour in Wyoming; the accident landed Cuddy in the hospital with severe head trauma and “diffuse axonal injury,” she says. “It’s hard to predict the outcome after that type of injury, and there’s not much they can do for you.”

Cuddy had to take years off from school and “relearn how to learn,” she explains. “I knew I was gifted--I knew my IQ, and didn’t think it could change. But it went down by two standard deviations after the injury. I worked hard to recover those abilities and studied circles around everyone. I listened to Mozart--I was willing to try anything!” Two years later her IQ was back. And she could dance again.

She returned to college as a 22-year-old junior whose experience with brain trauma had galvanized an interest in psychology. A job in a neuropsychology lab proved dull, but she found her passion in social psychology. Cuddy graduated from Boulder in 1998, then began a job as a research assistant to Susan Fiske ’73, Ph.D. ’78 at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. Fiske became her mentor for the next seven years; in 2000 they both moved to Princeton, where Cuddy earned her doctorate in social psychology in 2005; her dissertation investigated aspects of warmth and competence perception. (Fiske remains on the Princeton faculty, and the two women still collaborate on research.)

Cuddy taught at Rutgers, then was recruited to join the faculty at the Kellogg School of Management at Northwestern. She spent two years in Chicago before moving to Boston in 2008 to join the faculty at Harvard Business School, where she teaches courses in negotiation and power and influence.

Warmth—does this person feel warm or cold to me?—is the first and most important interpersonal perception. It no doubt has roots in survival instincts: determining if another human, or indeed any organism, is “friend or foe” can mean life or death.

Warmth is not only perceived first, but accounts for more of someone’s overall evaluation than competence. The warm/cold assessment amounts to a reading of the other’s intentions, positive or negative.

Competence is assayed next: how capable is someone of carrying out those intentions? “If it’s an enemy who’s competent,” Cuddy explains, “we probably want to be vigilant.” Surprisingly, in their self-perceptions, individuals value competence over warmth. “We want other people to be warm, but we want to be competent,” she says. “We’d rather have people respect us than like us.” (Cuddy thinks this human tendency represents a mistaken judgment: “Social connections will take you farther than respect.”)

There’s an interesting asymmetry. Many acts can indicate competence: scoring well on a College Board exam (SAT), for example, or knowing how to handle a sailboat, or deftly navigating through a software application. Demonstrating a single positive-competent behavior tends to broaden into a wider aura of competence: someone with a high SAT score, for example, will be viewed as generally competent. In contrast, a single negative-competent behavior--not knowing how to sail, for example--does not generalize into a perception of overall incompetence: it will simply be dismissed as, say, an unlearned skill. “Positive competence is weighted more heavily than negative competence,” Cuddy summarizes.

With warmth, the inverse applies. Someone who does something nice, like helping an elderly pedestrian across an intersection, is not necessarily seen as a generally nice person. But a single instance of negative-warmth behavior--kicking a dog, say--is likely to irredeemably categorize the perpetrator as a cold person.

In other words, people feel that a single positive-competent, or negative-warmth, actreveals character. “You can purposely present yourself as warm--you can control that,” Cuddy explains. “But we feel that competence can’t be faked. So positive competence is seen as more diagnostic. On the other hand, being a jerk--well, we’re not very forgiving of people who act that way.”

This principle has powerful leverage in public life, where a single misstep in the warmth-negative category can prove fatal. In the 2006 U.S. senatorial campaign in Virginia, for example, Republican incumbent George Allen had a wide lead over challenger Jim Webb, but stumbled at a campaign event in August. Allen singled out a young man in the crowd, S.R. Sidarth, a U.S. citizen of Indian descent, who was filming Allen’s campaign stop as a “tracker” for the Webb campaign: “This fellow over here with the yellow shirt--Macaca, or whatever his name is….” “Macaca” was widely taken as a derogatory racial epithet. Allen’s lead in voter polls tumbled, and Webb won the seat. Another example is the sudden destruction of Hollywood actor Mel Gibson’s image wrought by his alcoholic anti-Semitic rant after being stopped for drunk driving in 2006.

The human tendency to generalize from single perceptions produces the familiar “halo effect,” the cognitive tendency to see people in either all-positive or all-negative ways that psychologists have documented since at least 1920. Certain central traits, like attractiveness, tend to affect perceptions of unrelated dimensions and induce a generally positive take on someone. (“Attractive people are generally seen as better at everything,” says Cuddy.) But the halo effect “assumes that you’re not comparing the person to anyone else,” she adds. “And that’s almostnever true. Unless you’re a hermit, social comparison is operating all the time.”

Very often, what’s really being compared are not individuals, but stereotypes. The halo effect hints at the power of mindsets, which are strong enough to override direct perceptions. And in rating warmth and competence, we inevitably take cues from stereotypes linked to race, gender, age, and nationality--assuming, for example, that Italians will be emotionally warmer than Scandinavians.

Some stereotypes lean on each other. “Let’s say you’re down to the final two in a hiring situation,” Cuddy says. “This is where ‘compensatory stereotyping’ kicks in. The search committee is likely to see one candidate as competent but not so nice, and the other as nice, but not as competent.” In other words, the lens of social comparison distorts perception by exaggerating and polarizing the differences. This clarifies the comparison, but does so by introducing incorrect information. The same rule applies in a political election. Think of the 2000 campaign: George W. Bush was perceived as an amiable but inexperienced policy lightweight, while Al Gore came off as well-qualified but lacking the common touch.

The same pattern shows up when we judge individuals. In a 2009 Harvard Business Review article, “Just Because I’m Nice, Don’t Assume I’m Dumb,” Cuddy wrote, “People tend to see warmth and competence as inversely related. If there’s a surplus of one trait, they infer a deficit of the other.” In a business context, she says, this means that “The more competent you are, the less nice you must be. And vice versa: Someone who comes across as really nice must not be too smart.” This pattern is the opposite of the halo effect: a plus on one dimension demands a minus on the other. The unconscious logic might be: If she were really competent, she wouldn’t need to be so nice; and conversely, the highly competent person doesn’t have to be nice--and may even have reached the top by stepping on others.

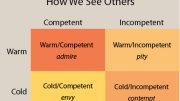

The intersection of warmth and competence generates four ideal types (see illustration), a model Cuddy has developed over the past few years with Susan Fiske and Peter Glick, of Lawrence University. Their schema allows social psychologists to disaggregate the notion of prejudice, which is too often conceived merely as an us/them phenomenon: “My in-group is superior to your out-group.” It’s not that simple. “That [binary] model predicts almost nothing about the treatment of an out-group,” Cuddy says. “Not prejudice, the emotional component, and not discrimination, the behavioral component.” The content of the stereotypes is also relevant: stereotypes are systematic. Almost every out-group will fall into one quadrant of the warmth/competence map, and that quadrant will predict how it is treated.

The most advantaged category, of course, is warm/competent; that perception evokes admiration and two kinds of behavior: active facilitation (helping) and passive facilitation (cooperating). At the other extreme, the cold/incompetent group elicits contempt and two markedly different behaviors: passive harm (neglect, ignoring) and active harm (harassment, violence). In both cases, the emotions and behaviors are unambiguous, predictable, and directly linked to the warmth/competence perception.

In contrast, groups seen as cold/competent evoke envy, and “envy is an ambivalent emotion--it involves both respect and resentment,” Cuddy explains. Envy also drives ambivalent behavior. In 1999, for example, white supremacist and neo-Nazi Matthew Hale, despite his strong anti-Semitic beliefs, hired Frankfurter professor of law Alan Dershowitz to represent him in a suit against the Illinois Bar Association. “Now, Matthew Hale doesn’t like Alan Dershowitz,” Cuddy says, “but he clearly sees him as competent.” Another example: a new pupil in a mathematics class is told to pair up with another student to work on a problem. Research suggests that a pupil who knows no one in the class will tend to partner with an Asian student; Asians are stereotyped as cold/competent. “People are willing to team up with them, but it’s only out of self-interest,” says Cuddy.

However, there’s a far darker side to the cold/competent stereotype. “If you look at the groups that were targets of genocide, at least over the last century, they tend to be these groups” perceived as cold/competent, Cuddy says, citing qualitative evidence. (She has not collected data on the question.) “In times of economic instability, when the status quo is threatened, groups in this cluster are scapegoated--Jews in Germany, educated people in Cambodia, the Tutsi in Rwanda.” In general, she explains, this cluster “tends to contain high-status minority groups: they’re seen as having a good lot in life, but there’s some resentment toward them. ‘We respect you, there’s something you have that we like, but we kind of resent you for having it--and you’re not the majority.’ Asian-Americans, career women, and black professionals also tend to be perceived in the cold/competent quadrant.”

For those seen as cold/competent, sexual harassment can become a form of what Cuddy calls “active harm.” “It’s very aggressive--it’s not about flirtation,” she explains. “The lay theory was that sexy women are the targets of sexual harassment--the sexy secretary who shows cleavage. But the actual targets tend to be women who are more masculine and very successful. It seems to be a form of active harm directed at a group that’s threatening--a way of ‘putting them in their place,’ or even expelling them from the environment.”

The warm/incompetent quadrant, too, evokes an ambivalent emotion: pity, which fuses compassion and sadness. People are more likely to help groups in this cluster, like the elderly, but also much more likely to ignore and neglect them, says Cuddy. Furthermore, the more strongly one subscribes to the warm/incompetent stereotype, the more likely one is to both help and ignore such people. “It depends on the situation,” she says. “If you’re at a backyard barbecue, you’re more likely to help the elderly person. In the office, you’ll probably neglect them.”

On the job, many studies have shown that working moms are seen as both significantly nicer--and significantly less competent--than working fathers or childless men and women. “We call this the ‘motherhood penalty,’ ” says Cuddy. “At the same time, fathers experience the ‘fatherhood bonus.’ They’re viewed as nicer than men without kids, but equally, if not more, competent. They’re seen as heroic: a breadwinner who goes to his kid’s soccer game once in a while. But in or out of the office, working mothers experience a fair bit of hostility from people who think they should be at home with their kids. Researchers have documented thousands of cases of motherhood discrimination; a mother being laid off might hear things like, ‘I know you wanted to be at home anyway.’ ”

Cross-cultural research shows that the only group that consistently occupies the cold/incompetent “contempt” quadrant is the economically disadvantaged: the homeless, welfare recipients, poor people. “They’re blamed for their misfortune,” Cuddy says. “They are both neglected and, at times, become the targets of active harm.” Deep-seated cognitive patterns may prepare the way for maltreatment. “There’s an area of the brain, the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), that is necessary for social perception,” she explains. Recent imaging research showed no activation of the mPFC in response to pictures of homeless people, Cuddy points out: “People are not even recognizing them as human.”

Nonverbal data are powerful factors in our assessments of others. For example, “A lot of what reveals lying happens below the neck,” Cuddy explains. “Lying leaks out physically. To come across as authentic, your verbal and nonverbal behavior must be synchronized.” She became interested in identifying which nonverbal behaviors indicate warmth and competence. “Appropriate self-disclosure, the use of humor, and natural smiles all signal warmth,” says Cuddy. “So do behaviors called ‘immediacy cues,’ like leaning toward someone, communicating on the same physical plane, and being closer physically, although the ideal distance varies greatly across cultures.”

Recently, she has begun to study nonverbal cues that drive perceptions of competence, which relate directly to one’s position in the social pecking order: a star athlete, for example, enjoys far higher status than a journeyman. “Dominance and power are highly correlated with perceived competence,” she says, “and people make inferences of competence based on how dominant someone appears.”

“In all animal species, postures that are expansive, open, and take up more space are associated with high power and dominance,” she says. “Postures that are contractive--limbs touching torso, protecting the vital organs, taking up minimal space--are associated with low power, being at the bottom of the hierarchy. Any animal you can think of, when it’s prey, makes itself as small as possible.”

In primates, these postures also correlate with testosterone and cortisol levels. Expansive, high-power postures mean (in both sexes) high testosterone, a hormone that animal and human studies connect with dominance and power, and low levels of cortisol (the “stress” hormone), while the inverse holds for contractive, low-power postures. “Those endocrine profiles are associated with disease resistance,” Cuddy says. “Low testosterone and high cortisol make you very vulnerable to diseases, so you’re more likely to be picked off by whatever comes through. At the top, you’re more disease-resistant.”

Until recently, primatologists believed that those who inherited high-power neuroendocrine profiles became the dominant creatures in their groups, the so-called alpha males or females. “But it turns out that those hormone levels change when you take on the dominant role,” Cuddy explains. “If an alpha is killed and another primate has to take over that position, his or her testosterone and cortisol levels will change in just a few days. Likewise, if you get pushed to the bottom, your hormone profile shifts. It’s both cause and effect. It’s possible that slight innate differences in neuroendocrine profiles are greatly exaggerated by role assignment.”

In a recent paper published in Psychological Science, Cuddy, Dana R. Carney, and Andy J. Yap (both of Columbia) report how they measured hormone levels of 42 male and female research subjects, placed the subjects in two high-power or low-power poses for a minute per pose, then re-measured their hormone levels 17 minutes later. They also offered subjects a chance to gamble, rolling a die to double a $2 stake. The results were astonishing: a mere two minutes in high- or low-power poses caused testosterone to rise and cortisol to decrease--or the reverse. Those in high-power stances were also more likely to gamble, enacting a trait (risk taking) associated with dominant individuals; they also reported feeling more powerful. “If you get this effect in two minutes, imagine what you get sitting in the CEO’s chair for a year,” Cuddy says.

This work has practical applications--for example, in the M.B.A. program at the business school, where classroom participation determines 50 percent of a student’s grade. There, women students have a harder time getting airtime, and speak more briefly when they do talk. Cuddy has observed that women are also much more likely to cross their legs and arms, or to lean in: low-power poses. While men raise their hands straight up, women tend to raise them with an elbow bent 90 degrees, commanding less space. “The guys spread their arms out and take up as much space as they can,” Cuddy says.

She and Carney, who teaches at Columbia’s Graduate School of Business, have begun to advise their women M.B.A. students to stop crossing their legs and minimizing their physical presence--and instead to raise their adjustable classroom chairs as high as possible while keeping feet on the floor, to “be as big as you are.” Some former students have told her that they’ve used this advice to good effect in job interviews. And recently, she and Carney launched a study to measure the effect on fundraising success of having telemarketers at the Columbia University Alumni Giving Center adopt high- or low-power postures.

“Tiny changes that people can make can lead to some pretty dramatic outcomes,” Cuddy reports. This is true because changing one’s own mindset sets up a positive feedback loop with the neuroendocrine secretions, and also changes the mindset of others. The success of venture-capital pitches to investors apparently turns, in fact, on nonverbal factors like “how comfortable and charismatic you are. The predictors of who actually gets the money are all about how you present yourself, and nothing to do with content,” Cuddy says, citing research by Boston College doctoral student Lakshmi Balachandra (a research fellow at Harvard Law School’s Program on Negotiation), who studied 185 venture-capital pitches and found that variables like “calmness,” “passion,” “eye contact,” and “lack of awkwardness” were strong predictors of success.

Nonverbal states like confidence are infectious in part because “People tend to mirror each other,” Cuddy says. “There are dedicated ‘mirror neurons’ in the brain.” Mirroring may facilitate social connection: by enacting the same nonverbal behaviors, individuals increase social cohesiveness. A simple example is smiling. A natural smile (which involves muscles around the eyes, unlike a fake smile) produces physiological feedback that makes the smiler feel happier. Someone watching this involuntarily mirrors the smile. “Even on the phone, you ‘hear’ them smiling back,” Cuddy says, “and this makes you even happier.” Thus a feedback loop kicks in, both between the people and within each individual, as the body produces neurochemicals that correlate with happy feelings.

Whether we smile or frown with someone (frowns trigger a different feedback loop) has much to do with what traits we believe them to possess--such as warmth or competence. Social psychologists have long understood the “Pygmalion effect”: we treat people in ways consistent with our expectations of them, and in so doing elicit behavior that confirms those expectations. “If you think someone’s a jerk, you’ll behave toward them in a way that elicits jerky behaviors,” says Cuddy. “And then you say, ‘See? He is a jerk!’ This is one of the dangers of stereotypes. When we elicit behaviors consistent with the stereotypes we hold, we tell ourselves, “See? The stereotypes are right!”

Finally, those powerful high-testosterone, alpha-dog people may be more prone to deploying stereotypes. Cuddy refers to Dana Carney’s theory that feeling powerful is disinhibiting, so you stereotype more; if stereotypes are automatic, to avoid stereotyping requires an inhibiting process. A second explanation is that “Top people tend to see everyone under them as the same,” says Cuddy. “It’s OK if they confuse Employee A with Employee B--they’re not going to lose their job because they offended somebody beneath them. Lower-status people need to be more vigilant; stereotypes won’t give them all the information they need. Stereotypes are cognitive shortcuts you take when you don’t have that much to lose.”

Leaders often see themselves as separate from their audiences, says Cuddy. “They want to stake out a position and then try to move audiences toward them. That’s not effective.” At the business school, she notes, many students tend “to overemphasize the importance of projecting high competence--they want to be the smartest guy in the room. They’re trying to be dominant. Clearly there are advantages to feeling and seeing yourself as powerful and competent--you’ll be more confident, more willing to take risks. And it’s important for others to perceive you as strong and competent. That said, you don’t have to prove that you’re the most dominant, most competent person there. In fact, it’s rarely a good idea to strive to show everyone that you’re the smartest guy in the room: that person tends to be less creative, and less cognitively open to other ideas and people.”

Instead, says Cuddy, the goal should be connecting. When people give a speech or lead a meeting, for example, they tend to exaggerate the importance of words. They “care too much about content and delivering it with precision. That makes them sound scripted.” Far better, she advises, to “come into a room, be trusting, connect with the audience wherever they are, and then move them with you.”