Wendy Lesser ’73, the founding editor of The Threepenny Review and a critic of unusual scope (witness recent books on reading and on Shostakovich), has now written You Say to Brick: The Life of Louis Kahn (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, $27), about the zenith of architectural creativity. The title (from Kahn’s elemental teaching about the essence of materials, “You say to a brick, ‘What do you want, brick?’…”) weaves together a biography; Lesser’s visits and reactions to some of Kahn’s most significant works; and an intriguing speculation about the inner drives that propelled him both to brilliant design and to numerous affairs, illegitimate children, and chaotic business practices. He was a modernist who looked backward, in a colleague’s assessment—to the essential forces of building and of life. In Lesser’s telling:

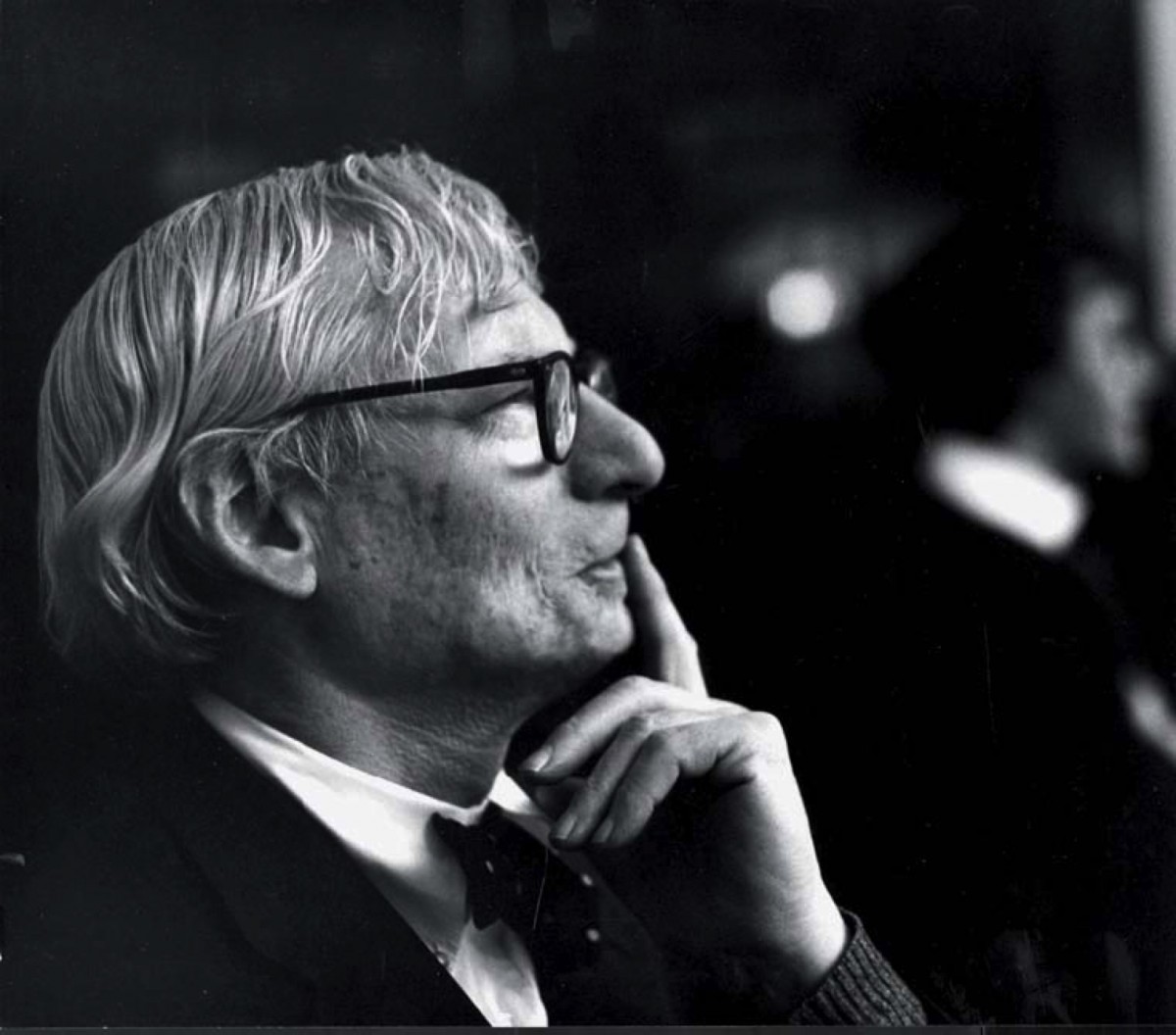

Louis Kahn

Photograph by Robert Lautman/National Building Museum

…“Desire is irresponsible,” Lou himself commented. “You can’t say that desire is a sense of purity. It has its own purity, but in the making of things great impurities can happen.”

He saw the danger, but he did not disown it. And this respect, if that is the right word, for desire, for the original impulse that motivates all making and taking, was essential to Kahn’s views, governing his sense not only of how life might be lived but also of how architecture might be practiced. “I do not believe that beauty can be deliberately created,” he wrote in his notebooks. “Beauty evolves out of a will that may have its first expression in the archaic. Compare Paestum with the Parthenon. Archaic Paestum is the beginning. It is the time when walls parted and the columns became and Music entered architecture.…The Parthenon is considered more beautiful, but Paestum is still more beautiful to me. It presents a beginning within which is contained all the wonder that may follow in its wake.”

To insist on a perpetual sense of wonder—or to argue, as Kahn did, that a great building “must begin with the unmeasurable, must go through measurable means when it is being designed and in the end must be unmeasurable”—is to resort continually to the same impulses that fuel desire. One must be constantly acting on one’s own feelings, one’s own responses: Is this what I really wanted to do? Does this or that element need to be altered to accomplish what I envisioned? How about this unexpected factor—can I use it to get back to my original idea, but in a new way? The process is all about beginnings, for Kahn. And it is in the beginning, of course, that every desire burns with its most searing intensity. Kahn’s wish to return there, repeatedly, was perhaps his most salient characteristic as both an architect and a man.

The two were, in any case, probably not separable.