As the business school fosters budding entrepreneurs along Western Avenue, an older-fashioned way of innovating—and the birth of Kendall Square in Cambridge as a world center of doing so—are on display at Baker Library, in an exhibition on Edwin H. Land ’30, S.D. ’57, and the Polaroid Corporation (through late July).

Displaying for the first time objects drawn from the company’s archive of 1.5 million items donated in 2006, “At the Intersection of Science and Art” (a title taken from Land himself) abounds in surprises. There are the early discoveries of polarizing filters—and their use in hilarious adjustable sunglasses (above) and even automobile-shaped spectacles for viewing a 3-D Polaroid movie about Chrysler’s assembly line, made for the 1939 World’s Fair. There are wartime inventions like the Vectograph: 3-D images used for aerial reconnaissance. And then the “Aha!” moment, when Land’s daughter, on a family vacation in Santa Fe in 1943, asked, in his words, “why she could not see at once the picture I had just taken of her.…Within the hour, the camera, the film, and the physical chemistry became so clear to me” that he discussed it all with the company’s patent attorney.

Image courtesy of Baker Library, Harvard Business School

The resulting work leading to the debut of the instant-photo system is the exhibition’s culmination. Who would have expected that some of the foundational drawings were by Maxfield Parrish Jr. (the son of the painter who set the standard for kitsch)?

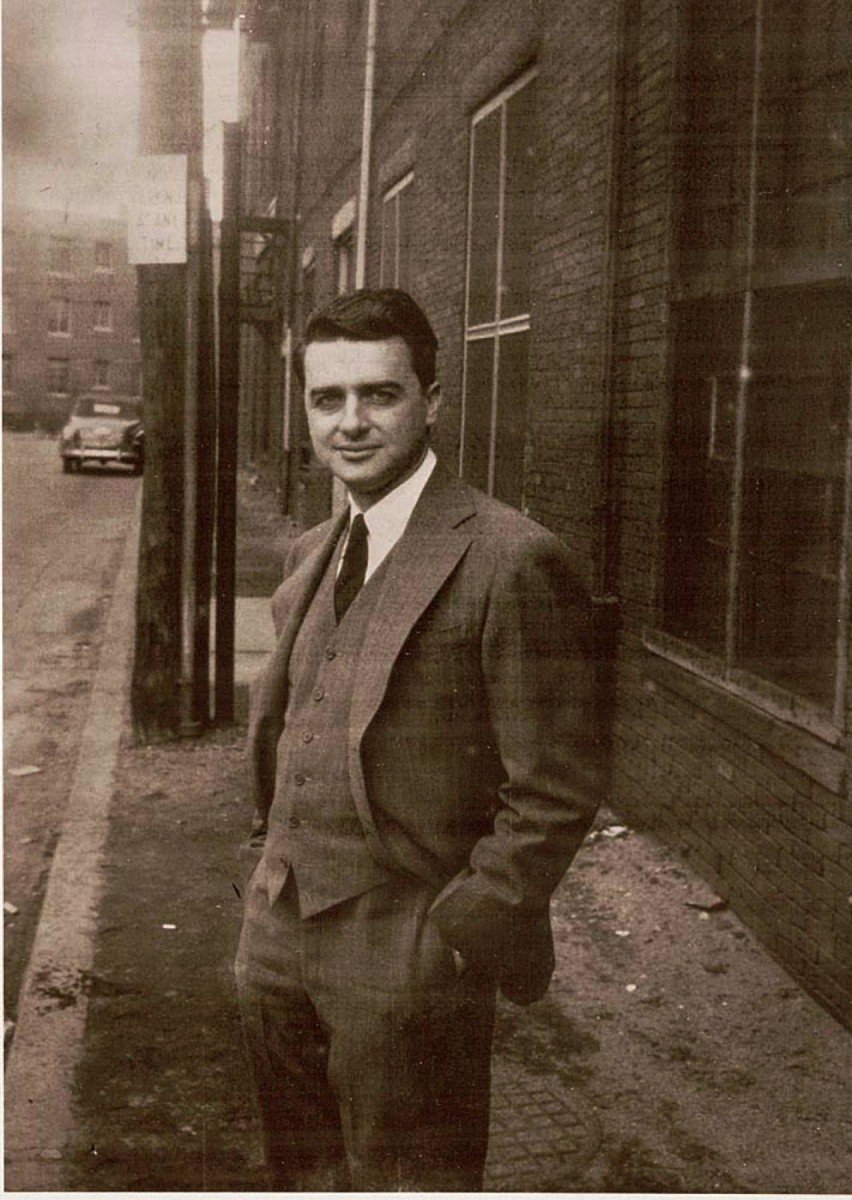

There are also intriguing hints at Boston’s evolution. A photo of the absurdly handsome Land at Main and Osborn Streets in Cambridge, taken in 1946 (right), shows what a backwater the area was then: no suggestion of today’s stratospheric rents and kale-salad joints. And a (manually) typed September 2, 1948, memorandum from R.T. Kriebel to Polaroid superiors, with Land cc’d, on where to launch the new camera system, disses the home-town team: “Boston is notoriously slow in response to new products.” (The savvy marketers chose the Friday after Thanksgiving to unveil their handiwork, at the Jordan Marsh department store; all 56 units sold.)

Image courtesy of Baker Library, Harvard Business School

Amid a billion smart phones and a zillion selfies, Polaroid’s miracle cameras are mostly history. But Polaroid’s spirit lives on. “The small company of the future,” Land wrote in 1937, “will be as much a research organization as it is a manufacturing company.…” Technology drove the firm, but Land was clear that “the aesthetic purpose” of his photography system “is to make available a new medium of expression…to individuals who have an artistic interest in the world around them.” He himself enrolled at Harvard in the fall of 1926, left after that term to work on polarizing materials, returned in 1929, and then left in 1932 to form a company with a physics instructor, anticipating Bill Gates ’77, LL.D. ’07, and Mark Zuckerberg ’06. Given Land’s aesthetic drive, exhibition curator Melissa Banta draws an analogy to another famous dropout: “Land was a real model for entrepreneurs like Steve Jobs,” who were interested in “creating elegantly designed products that served human needs.”