On a june night in 1910, fire trucks raced through Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and found not a house in flames, but a bonfire atop Fonthill, the fantastical 44-room concrete home of Henry Chapman Mercer, A.B. 1879. That bonfire let Mercer celebrate his birthday, maintain the tradition of fires on St. John’s Eve, and inaugurate his new home by demonstrating its fireproof qualities. (The journal Cement Age duly noted: “This is the sort of story that is causing the insurance man to sit up and take notice.”)

Mercer was recognized by then as a leading ceramicist of the Arts and Crafts movement, a distinction he came to in a roundabout way. After college he studied, but never practiced, law. Instead, he traveled for almost a decade, pursuing art, history, and archaeology. By 1894, he had been appointed curator of American and prehistoric archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania Museum, but he held that post for just three years, parting ways with museum authorities as a result, in part, of his curmudgeonly personality. (A note in his copy of A Farewell to Arms hints at his style: “As convincing as a tapeworm. As charming as a bottle of dead flies.”)

A Mercer-designed tile

Photograph by Harvard Magazine/JC

Even before leaving the museum, Mercer had developed a new approach he described as “archaeology turned upside down.” Rather than beginning millennia before, he started with the recent past and worked back to its historical origins. This grew from his fascination with tools, made obsolete by industrialization, that he found discarded or offered in penny lots at country sales. They “give us a fresh grasp upon the vitality of the American beginning,” he wrote. “At first, illustrating an humble story, they unfold by degrees a wider meaning, until at last the heart is touched.” He created an elaborate 13-part taxonomy for tools (broadly defined) and assembled a vast collection at the heart of the Bucks County Historical Society’s museum that now bears his name.

That museum reflected two sides of Mercer: learned in its content yet creative in its presentation. Its systematically organized collection served students of material culture—including Mercer himself, whose pioneering scholarship was so fundamental that his 1929 Ancient Carpenters’ Tools, still in print, remains a basic text. Its displays, meanwhile, were extravagant and exuberant—an effort to capture the eye and the imagination. A central court rose five stories, surrounded in Escher-like profusion by small galleries, ramps, and stairs. On the ground floor were cigar-store Indians (Tools of Commerce); hanging balanced in the air above were a Conestoga wagon and several penny-farthing bicycles (Tools of Transport); at the very top was a gallows (a Tool of Government).

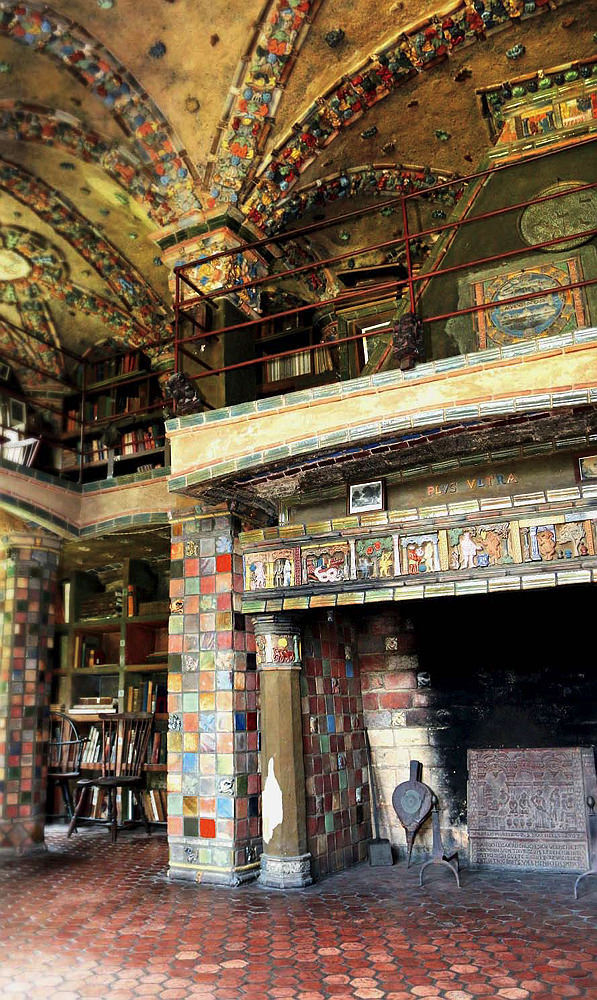

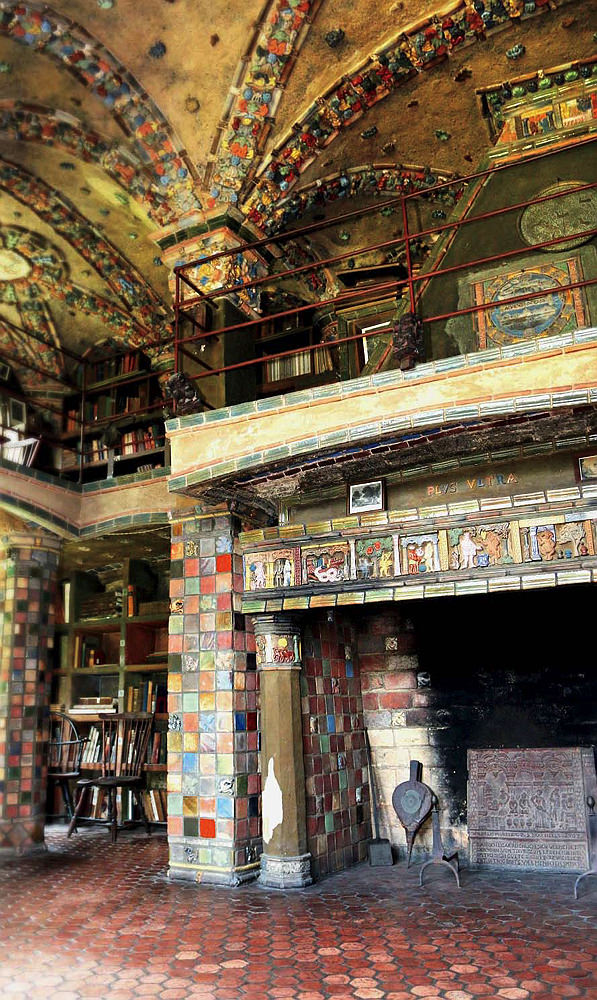

An interior view of Fonthill Castle

Photograph courtesy of the Mercer Museum and Library

Exterior view of Fonthill

Photograph by Kevin Giannini/Alamy Stock Photo

An interior view of the Mercer Museum

Photograph by Allure West Studios/Courtesy of the Mercer Museum and Library

Beyond building his collection, he wanted to understand how those obsolete tools were used, and even to revive a dying or lost craft. Fearful that “so beautiful an art as that of the old Pennsylvania German potter…should perish before our eyes,” he chose ceramics, which he learned from one of the last redware potters in Bucks County. Working with clay sparked Mercer’s creativity; he wrote of how his imagination was fired by “the manner in which mother earth grows out of the human touch into bowl or vase.” Ceramics also drew on his artistic talents: he was an amateur painter and etcher, and at Harvard had studied art history with Charles Eliot Norton. By 1898, he had founded the Moravian Pottery and Tile Works. All its handmade tiles were his original designs or based on historical models he had adapted, and reflected the Arts and Crafts movement, then an important influence on American design.

He soon earned major commissions, including the floors for Isabella Stewart Gardner’s Fenway mansion and the rotunda of the Pennsylvania State Capitol, which he filled with almost 400 mosaics (one of his patented tile processes) displaying the state’s history, industries, plants, and animals. Recognition was both artistic and commercial. His tiles won a grand prize at the 1904 World’s Fair, and were sold in every state and overseas. The Pottery remained profitable even as the Arts and Crafts period waned, and still produces tiles while serving as a living-history museum.

Simple geometric tiles may have been the Pottery’s mainstay, but what was essential to Mercer was the artistic quality of his work. If plain tiles were all he produced, he told his workmen, he “might as well make soap.” Instead, his tiles told stories from sources as varied as the Bible, folk tales, Dickens’s Pickwick Papers, and Wagner operas.

A Mercer-designed tile

Photograph by Harvard Magazine/JC

Architects prized these decorative tiles, and Mercer, although untrained, was a sometime architect himself, designing both Fonthill and the Mercer Museum while creating the methods used to build them. Each was medieval in appearance but modern in construction: early examples of using reinforced concrete beyond industrial settings, built when Frank Lloyd Wright and Thomas Edison were also exploring its residential uses. He took pleasure in the rough imperfections of concrete and chastised architects who tried to disguise them, “ashamed of the mold, the welts and the boards which show that the walls were cast,…the richness of the texture that, like the rocks of the world, reveals creative work to the geologist.”

At his death, the distinguished archaeologist David Randall-McIver could refer to Mercer as “an extraordinary figure…straight from the Renaissance.” His classmate J.T. Coolidge wrote in an obituary that he was a “man of unusual character and imagination. Handsome, winning, interesting—and odd.” The reality can probably be found in a combination of those two characterizations.