The lecture had a playful, topical title—“Did Early Christians Invent Fake News?”—but the questions Karen L. King had come to wrestle with that night, as rain fell in sheets outside and a room full of students and scholars listened, were ancient and deeply serious. King, the Hollis professor of divinity and a historian of early Christianity, was speaking at Williams College, where she served as a visiting faculty member last fall. The questions at the center of her talk have occupied her for decades: about the line between orthodoxy and heresy, and about the vehement, sometimes violent, debates that flared up in the first centuries after Jesus’s death.

Increasingly, these questions have led her to another one: “What work do stories do?” Storytelling is a deeply human act through which possibilities are realized, King says, and ways of living enabled or constrained. It matters which stories are told, and by whom. Take, for instance, Jesus’s marital status, a subject that has caused sharp controversy in King’s career. “What difference does it make if the story says Jesus was married or not?” she asks. “Well, it makes a big difference. It touches everything from people’s most intimate sense about their lives and their own sexuality to large institutional structures. It affects who gets to be in charge, who gets to preach and teach, who can be pure and holy. Should people be married or not? Can you be divorced or not? Is sexuality sinful, by definition? All of this depends on what kind of story you tell.”

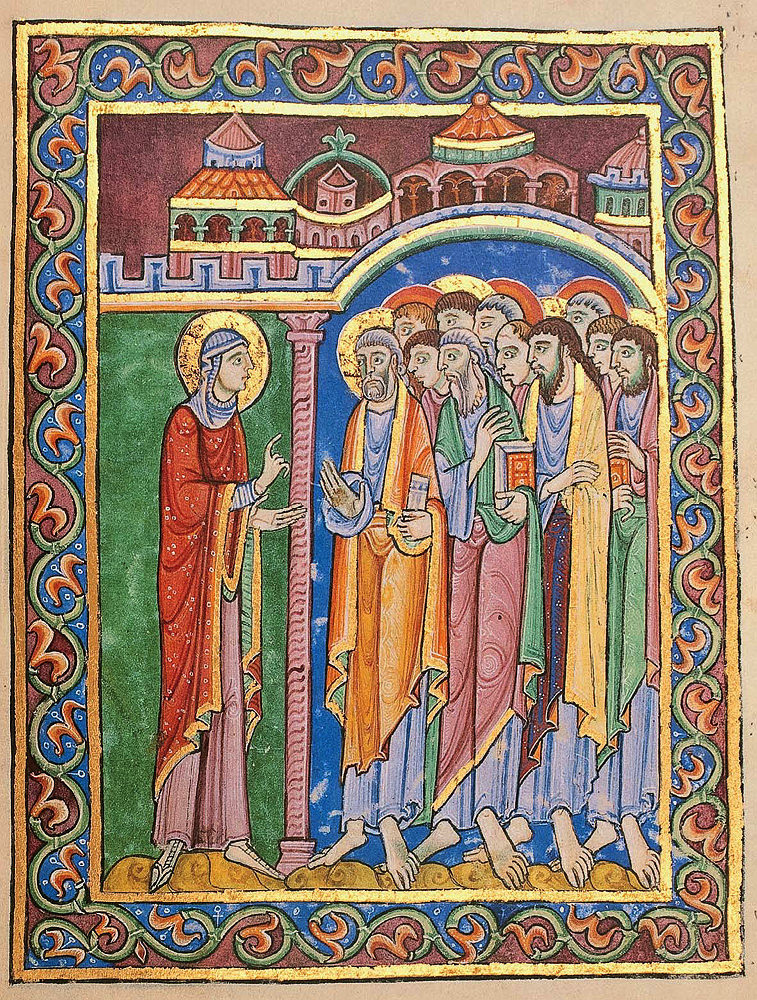

A medieval illuminated manuscript shows Mary Magdalene announcing the risen Christ to other disciples.

Illustration courtesy of Harvard Fine Arts Library, Digital Images and Slides Collection

Another example cuts close to King’s heart: for most of Christian history, religious art and literature depicted Mary Magdalene as a prostitute, a fallen woman who repented and anointed Jesus’s feet with oil. Modern historians now debunk this claim, demonstrating how the Mary Magdalene mentioned in the Bible only as an important follower of Christ became misidentified centuries later with another woman, an unnamed sinner, and from that confusion, was transformed into a harlot. “Think of the societal effect those representations have had,” King says, extending from late medieval poorhouses that took in women under the name of Mary Magdalene, to the infamous Magdalene Laundries in Ireland, where prostitutes and unwed mothers were confined well into the twentieth century. As King told the audience last fall, “The stories we live by, or the stories that are forced upon us, are crucial…There are no bare facts that are not entangled in storied worlds.”

It is through this lens that she thinks about those early arguments over Christianity. In the effort to establish a unified doctrine out of tremendous diversity, early church fathers like Irenaeus, the powerful second-century bishop of Lyon, who decried the “wicked and unfounded doctrine” of worshippers whose beliefs he opposed, not only proclaimed the “good news” of salvation; they also used “lies, polemics, and misdirection,” King said in her talk, to paint their opponents as cowards, deceivers, forgers, and false witnesses. And they won. Their theological vision triumphed and endured. The worshippers whom Irenaeus called Gnostics, or simply “those people,” were silenced and marginalized. Their sacred texts largely disappeared from the world, “at a considerable loss,” King said, “to Christian thought and practice.”

During the past century and a half, some of those texts, the ones that never made it into the Bible, have resurfaced, excavated from ancient Egyptian garbage heaps and burial sites, popping up in antiquities markets. Added together, they are much larger than the New Testament, and perhaps even than the whole Bible. The papyrus manuscripts reveal gospels (stories of the life and teachings of Christ), revelations, chants, poems, prayers, epistles, hymns, spiritual instructions. King’s scholarly mission is to “make room” for them in the Christian story. “There’s a way in which the standard narrative of early Christianity has a place for them already,” she says. “It’s called heresy.”

She smiles. “I mean, there’s nothing wrong with having normative categories—in fact, it’s important for having an ethics” and a shared social life. “But as a historian, you want to see the full data set.…I think a history of Christianity, which is a kind of story, serves us better if it has all the loose ends, the complexities, the multiple voices, the difficulties, the things that don’t add up, the roads not taken—all of that,” she says. “We need complexity for the complexity of our lives.” That’s what drew her in when she learned about the existence of other gospels beyond the four included in the New Testament. “I remember being attracted to this literature, and being told at the same time that it was wrong,” King says. “And part of me wanted to figure that problem out.”

Her 2003 book What Is Gnosticism? was one attempt at figuring it out. Tracing the term’s obscure lineage and contested definitions over time, the book was a major study challenging the very categories of orthodoxy and heresy. “What does Christianity look like if we don’t impose these categories on the data? If we just see these texts as simply there.” What would it look like to read these so-called Gnostic heretical texts just as Christian? “When you look at them not as wrong”—not as outside the data set but a part of the story—“what do they say? What do they show us that’s new or different about Christianity?”

Bernadette Brooten, Ph.D.’82, R.I.’90, L’00, a Brandeis religious historian whose research helped set the record straight about the existence of women apostles and synagogue leaders, has known King since she was a young professor. She says King’s meticulous textual interpretation and a willingness to question inherited frameworks enables “a more precise view of the literature,” Brooten says. “She asks, ‘What does our framework preclude us from seeing?’”

“Karen’s book really shifted the discussion,” says Princeton religion scholar Elaine Pagels, Ph.D. ’70, LL.D. ’13, whose 1979 bestseller The Gnostic Gospels dislodged the idea of early Christianity as a unified movement and launched the conversation that What Is Gnosticism? later took up. “Karen’s book showed how those terms”—Gnosticism, heresy, orthodoxy—“were coined, how those concepts were shaped, and how late they came into scholarly discourse,” says Pagels. “It’s like clearing away the brush, so that people could look at these texts with a much more open mind.”

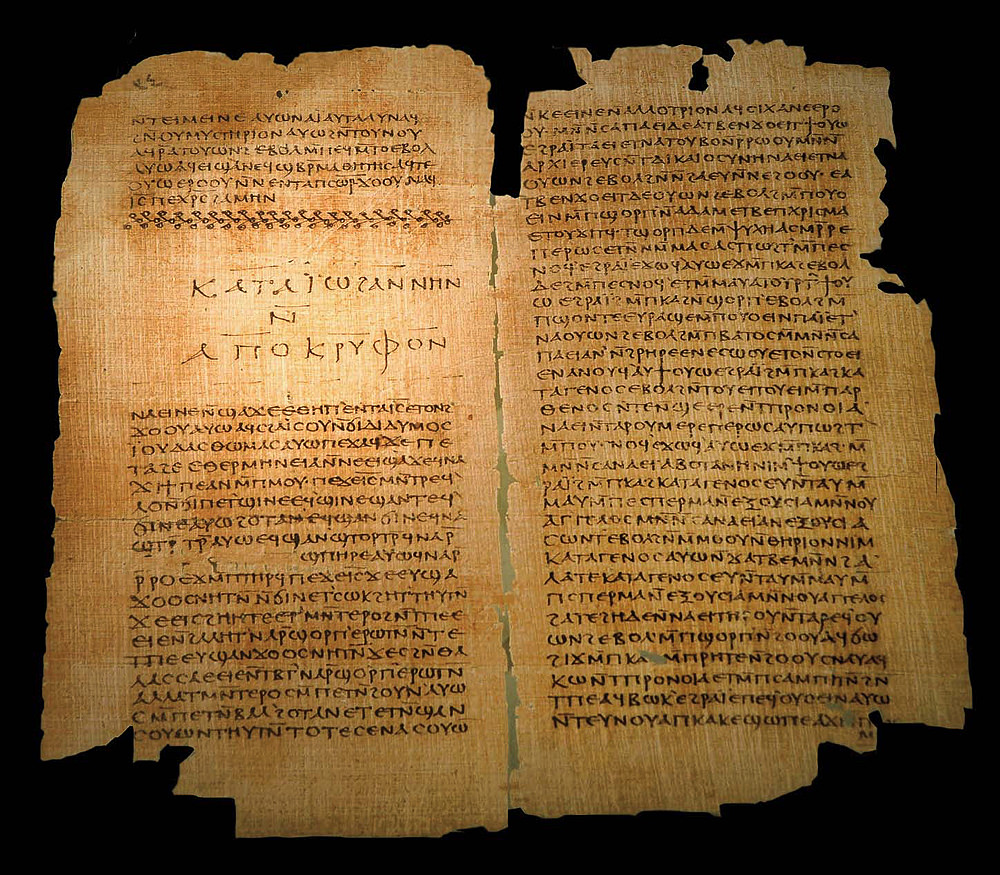

King likes to say that her career came out of a jar in Egypt. In 1945, a peasant named Muhammad Ali al-Aamman discovered a red earthenware jar full of manuscripts in the upper Egyptian desert, near a town called Nag Hammadi. He opened it, thinking there might be gold inside, but instead found 13 leather-bound papyrus books. He took the cache home to his mother, who used some of the papyrus for kindling. The rest found its way to the antiquities market and, eventually, to scholars. Now called the Nag Hammadi Library, 52 sacred texts survive, Coptic translations of Greek originals, offering vivid and varied interpretations of the Christian tradition. Some suggest, for instance, that the resurrection of Jesus was perceived through mystical visions, not fleshly encounters, or that God is best imaged as the Father-Mother, or simply as “the Good.”

On King's desk: a facsimile from two Nag Hammadi texts—the end of the Apocryphon of John, with a postscript title in large letters, and the beginning of the Gospel of Thomas, a collection of 114 sayings attributed to Jesus

Photograph by Patrick Chapuis/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images

As an undergraduate at the University of Montana in the early 1970s, King took a religious studies course from John Turner, one of the scholars working to edit and translate the Nag Hammadi texts. In class, she and other students read unpublished drafts of English translations that the wider public wouldn’t see for several years. It was electrifying. King had never imagined that there were early Christian writings beyond the Bible. “Why these texts and not those?” she wondered. And: “Who decided, and why?”

King came to college intending to be a doctor. She grew up in tiny Sheridan, Montana, a town lined with churches, where her mother was a teacher and her father the pharmacist. It was a helping profession, she says, and no one was turned away from his store, even when they couldn’t pay. “I was a Christian”—she remains one—“and when I went to college, I wanted, as many young people do, to do good in the world.” She settled on medicine.

But then she ended up in John Turner’s class, and found herself drawn to a major in religion. Medical schools, she was told, liked well-rounded students who’d studied beyond science.

After graduation, King, who’d grown up hiking and camping in the Rocky Mountains, took a solo bicycle trip down the West Coast. “From the driveway of the house in Sheridan, I biked my way to Missoula over the Continental Divide.” From there she took a train to Seattle and biked the Olympic Peninsula down the coast of Washington and Oregon into California. Afterward, she moved to New York City, to be a nanny in Calvin Trillin’s household, a job that had opened through a series of connections and coincidences—Trillin knew a Montana senator, who had met King’s college adviser at a party. She earned room and board and $65 a week. The experience was transformative: “my first time to do everything.” Museums, theaters, subways, street food. She discovered that she could stand at the back of the Metropolitan Opera for $5. Trillin’s wife, Alice, an English teacher, gave King books to read by authors who were invited to dinner. “Bud and Alice were great,” King says. Once they even hired a babysitter so she could go out with them.

While there, she applied to graduate schools in religion, still figuring she’d do medical school afterward. “Naively, I thought I could just take two or three years and do a Ph.D. in religion, just for fun, just for myself.” She chose Brown, in part, because the faculty there promised the chance to work with the Nag Hammadi literature. She spent seven years in the program, including a semester at Yale learning Coptic, and a year and a half in Berlin, studying with Hans Martin Schenke, a renowned Coptic scholar and translator who headed the Nag Hammadi project in East Berlin. This was 1982. “I was officially in West Berlin, but I would have to cross the border back and forth with these materials.” She was often stopped and made to wait hours at the border. Once she was strip-searched. It was all worth it: “Schenke really gave me my career,” she says. “He sat with me one day a week for over a year, taught me how to read manuscripts that were unpublished. That was my dissertation.”

By the time she finished graduate school, the study of religion had finally, fully taken hold. She accepted a job at Occidental College in Los Angeles, where she was asked to teach in women’s studies, an academic field just coalescing (King would help found the college’s women’s studies major and eventually chair it). She offered a course on women in the Bible and early Christianity. “And I remember my students saying, ‘Isn’t there anything good that they said about women?’” That sparked an awakening to a patriarchal side of the Christianity she was familiar with; meanwhile, newly recovered Christian texts from Egypt offered accounts of the feminine divine, and women who personified wisdom and strength, who were leaders and prophets.

“This became a significant part of my work—women, gender, sexuality, and what the early Christians said about it.” She has written, for instance, about the Gospel of Philip, a Nag Hammadi text that portrays Jesus as actually married (to Mary Magdalene) and his marriage as a “symbolic paradigm,” she says, “for the baptismal reunification of believers with their angelic selves” in what is called the “ritual of the bridal chamber.”

King spent 13 years at Occidental, where she co-taught an introductory course called “World Religions in Los Angeles.” Instead of a conventional syllabus, she and two other instructors divided the students into teams and asked them to pick “a something,” she says. “It could be the local farmacia”—which, in Latino culture, dispenses folk cures, religious amulets and candles, and limpias (“spiritual cleansings”)—or a church, synagogue, temple, or whatever. “LA has everything. So they went out and found religion.” She rented a bus and took the class to Pentacostal meetings, an Eastern Orthodox cathedral, Hindu temples, a Buddhist monastery, a Muslim community center, the temporary synagogue of recent Russian Jewish immigrants. “Sometimes we would pick a spot on the map and draw a circle around it and send the students to find out what religion looks like inside that circle,” King says. The students would start by asking, “What do you believe?” By the end of the course, they were paying attention to artwork and architecture, music or the lack of it, teaching and meditation, prayer. They watched how worshippers gathered, whether men and women sat separately; they traced groups’ immigrant history.

The class altered King’s understanding of how to treat early Christianity. The thesis of the course had been that religion is at least partly a function of place. “I started noticing that scholars would talk about the ‘pure essence of Christianity,’ or what Christianity ‘is’ as a singular thing. But what Los Angeles shows you is that religion is always fully embedded in the culture of its place.” It is diverse and always adapting. “And so that purity and synchronism are really artificial categories that don’t help us understand the complex beginnings of Christianity.” In Los Angeles, she once visited a Greek Orthodox church that displayed a timeline of Christian history in which the main trunk, from the origins of Jesus, led directly to the Orthodox Church, with Catholicism and Protestantism as side branches. In their own churches, of course, Catholics and Protestants each see themselves as the trunk.

King’s current ambition is to write a history of Christianity capacious enough to incorporate the silenced voices and marginalized texts—a fuller data set. It’s the book she has been edging toward all along. “I want us to understand that things are more complicated and complex than any simple story could possibly make them out to be....Now I’m working on these early Christian texts that are regarded as heresy, as paths not taken. But these texts were written before there was a biblical canon, a closed list of scriptures. They were written before there was a church architecture or building. They were written before you had fixed orders of authority, like bishops and priests. They were written before you had a creed. I began to realize that in fact the history of Christianity is the story of how all these texts came into being.”

On a Monday morning this past spring, King was guiding a classroom of Harvard Divinity School students through the Gospel of Mary, a text that’s become central to her scholarship. It is the only known gospel attributed to a woman and was the subject of King’s 2003 book, The Gospel of Mary of Magdala: Jesus and the First Woman Apostle. Like the Nag Hammadi cache, this text is a relatively late discovery, part of a fifth-century papyrus book found near Akhmim, Egypt, and purchased in 1896 by German author Carl Reinhardt. He brought the book to Berlin, where it became known as the Berlin Codex; it wasn’t fully translated from the Coptic until 1955.

The Gospel of Mary, from which several pages—perhaps half the text—are missing, elaborates on two post-crucifixion scenes mentioned briefly in the New Testament’s Gospel of John, in which Jesus appears and gives teachings, first to Mary Magdalene, and then to a larger group of disciples. Much scholarly attention to the text has focused on the dispute between Mary, who is reporting what Jesus said when he appeared to her, and Andrew and Peter, who not only question her account, but also challenge the idea that Jesus would give precedence to a woman. But in class that morning, King was interested in something else about the text: an idea called the “rise of the soul.”

The appeal to feminists and readers interested in early Christian women is obvious—a woman disciple, a leader trusted by the Savior—and King assumed they would be her audience for the book. But then she also began receiving letters from a different group: the dying and their loved ones. “There was an especially moving letter from a man who talked about his wife dying, and they would read the Gospel of Mary together.” She thought about how, when she wrote the book, her own father was dying. It occurred to her that the central point of the gospel wasn’t the dispute between disciples, but the “rise of the soul,” described as the movement toward God at the end of life.

In the text, Jesus’s disciples ask, “What is the nature of sin?” He replies, “There is no such thing as sin,” since God is perfectly good. Yet people suffer and die, King told the class, by clinging to the worldly “powers” of darkness and ignorance and desire and wrath that keep the soul tethered to “the things of the flesh.” “The more I thought about it,” King says, the more the gospel seemed to be about a spiritual path in this life as much as what might happen in the afterlife. “There is something in the story of the rise of the soul, of coming to terms with life and suffering and death, that people find very moving.”

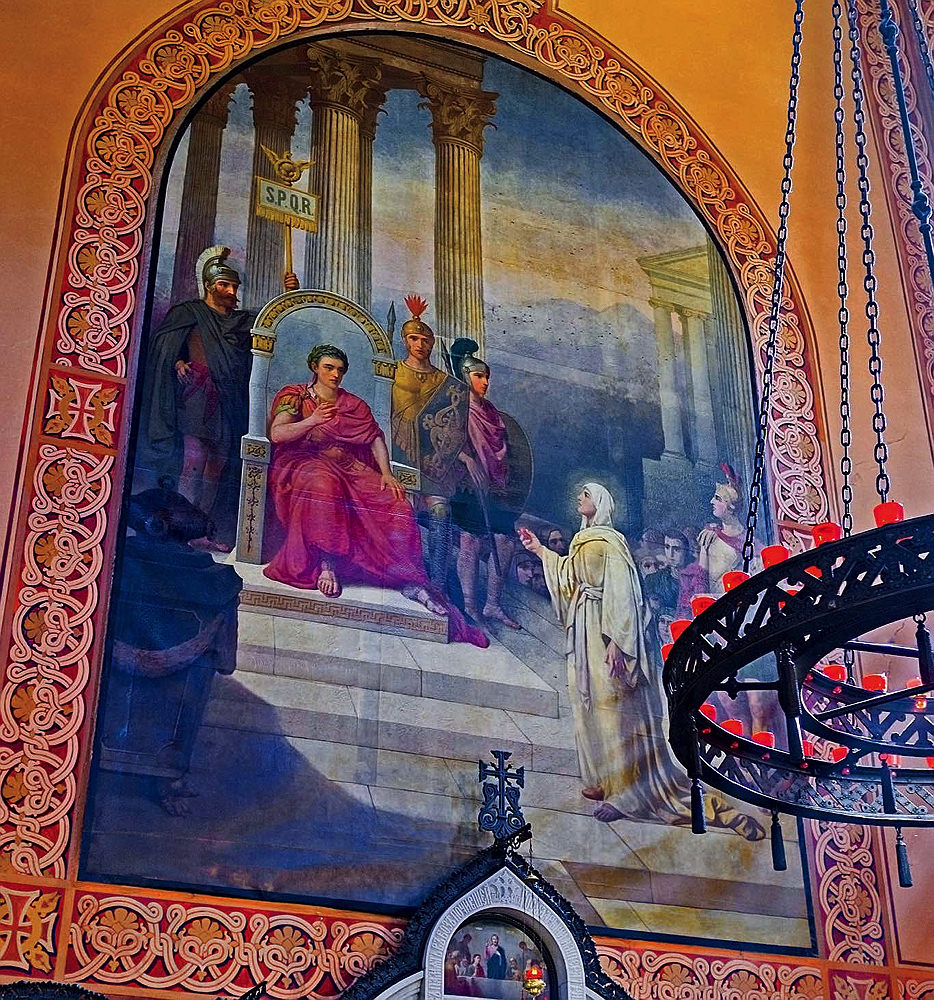

The Russian Orthodox Church of Mary Magdalene in Jerusalem shows her before Pontius Pilate with a red egg, a symbol of Jesus's resurrection.

Photograph by Ievgenii Fesenko/123RF Images

In a roundabout way, the Gospel of Mary and other early texts concerning women and gender led King to another avenue of research, on violence and torture. Both, she says, pay attention to the body. Early Christianity had different notions about “how to regard the fleshly body,” she explains—whether it is fundamentally sinful, or can be “radically transformed,” whether it is actually essential to being “fully human.” How much did sex or gender or ethnicity, or whether a person was elite or enslaved, ultimately matter? King did some research. She made some notes.

Then, 10 years ago, King was diagnosed with olfactory brain cancer. She underwent seven surgeries in three years, and received radiation treatment. “It was one of those are-you-going-to-make-it-or-not kind of things,” she says. For a while, no one was sure. “You know, as intellectuals, we spend a lot of time in our heads. Well, I spent a lot of time in my body. Just in my body.” When she was recovering, King went back and looked at the notes she’d made on the body in Christianity, and found them all “so absurd.” Everything went into the wastebasket. She started over.

This time, she decided to look at suffering and illness and what Christian texts from the first three centuries might have to say about them. She didn’t find much. “There’s a lot about healing and faith. But basically it’s, if you pray and you’re healed, God has healed you. If you pray and you’re not healed, then God doesn’t want you to be healed for some reason.”

But she did find abundant literature in the martyr tradition, with its detailed imagery of torture and violence. “Martyrdom is where Christianity gets very serious about bodies and suffering and death,” she says. “If you read any history of Christianity, you’ll read about the Age of the Martyrs, this period in the early church, during the first two centuries after Jesus’s death, where Christians who are willing to die for God to prove the faith are tortured and killed.” In fact, only a few Christians died this way, King adds, but because their executions happened in very public arenas, their stories exerted disproportionate influence on the tradition. Heretics were excluded from martyrdom—witnessing to the truth is the term’s literal meaning—but texts from Nag Hammadi and elsewhere show that “Christians of various stripes, including supposed heretics,” were executed for their faith.

The texts also raise a different question: whether trauma is necessarily at the center of the Christian story. Is Christianity “a story of trauma?” King asks. In some texts it isn’t Jesus’s death and resurrection that give meaning to Christianity. “It’s his teaching that is the center. It’s what Jesus taught. The Sermon on the Mount and his parables and turning away from this world toward God and prayer. That this is salvation.”

Instead of valorizing death, she continues, those worshippers asked, “‘Why does God allow this?’” when they were attacked. “They want to know, ‘What should we do?’ The death of Jesus becomes really important in that period, because it becomes a model of death and resurrection”—for some Christians, anyway. “But there were other Christians who said, ‘No, God doesn’t want this. God never wanted the death and cruelty and suffering involved in this.…You may get arrested and killed brutally, but it’s not the dying that saves you, it’s the teaching.’”

It was perhaps King’s openness to the full universe of early Christian writing—along with her research interest in gender and sexuality—that helped entangle her, several years ago, in a forgery controversy. In 2012, she unveiled a tiny fragment of 1,300-year-old papyrus, with words in Coptic, which, translated, read, “Jesus said to them, My wife…” The papyrus had come from an unnamed private collector, who’d reached out to King online. His claims about a potential scrap of early Christian writing “didn’t seem as odd to me as it might to somebody who hadn’t been working on” previously unknown texts, she says. Nevertheless, she was initially skeptical, waiting more than a year before responding. But when papyrus experts judged that the writing was most likely ancient, King took the fragment public; in an announcement at the Vatican, she called it the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife. If it proved to be dated to the early centuries, she said at the time, it would offer evidence, not that Jesus was actually married—“that’s not how it works” she says—but that some early Christians believed he was.

The backlash, both from academics and the general public, was passionate and intense, as was the media frenzy. The 2003 novel The Da Vinci Code had inflamed a fascination with the idea of a married Jesus. But immediately after King’s announcement, scholarly doubts emerged—and persisted, despite lab analyses that pegged the papyrus as authentically ancient and turned up no conspicuously modern ingredients in the ink. Eventually, investigative reporter Ariel Sabar tracked the fragment’s owner to Germany and Florida, and in a copiously detailed report in The Atlantic in 2016, revealed him to be a potential forger named Walter Fritz. The fragment was likely a modern fake.

All of this was deeply painful to King—though, her friend Bernadette Brooten notes, “she was always open to whatever the scientific and scholarly results would be.” But it also raised a new question.When was it, King wondered, that Christians first claimed that Jesus was unmarried? She found that the question had never really been fully researched. “I was sort of shocked. Nobody seemed to know.” Scouring early Christian texts and the work of other historians, she found a dizzying constellation of depictions: Jesus as both Father and Mother, as masculine and feminine, as an “unmanly” man, as a husband—to Mary Magdalene, to the Church—and as a eunuch, a circumcised Jew, a celibate, as the polygamous (heavenly) spouse of many virginal brides. The range of representations was “enormous.”

In her temporary office at Williams last fall, a couple of hours before her talk, King was flipping through a book of the Nag Hammadi translations, looking for the text that is perhaps her favorite in the whole collection: “Thunder Perfect Mind,” a beautiful, bewildering cascade of a poem, with a mysterious female speaker whose seemingly contradictory assertions read like a manifesto:

I was sent forth from the power

And have come to those who contemplate me

And am found among those who seek me.

King read aloud, her voice full of delight, thick with emotion.

I am the honored and the scorned.

I am the whore and the holy

I am the wife and the virgin

I am the mother and the daughter

I am the limbs of my mother

I am a barren woman who has many children

I’ve had many weddings and have taken no husband…

There’s a wildness about the poem that’s reminiscent of something author Sarah Sentilles, M.Div. ’01, Th.D. ’08, a former student, says about King’s work. “Karen understands that God is bigger than anything human beings can say about God,” she says. “So the more people say, the better. It’s the opposite of threatening—it’s liberative. And it’s, I think, profoundly ethical.”

King skipped to the poem’s final lines:

There they will find me

And they will live and not die again.

This, King says, is part of what is valuable about so-called heretical texts—their mystery, their strangeness, their refusal to make the story simpler. And their closeness to the beginning, when the ideas and revelations that would become Christianity were still new and contested and electric.