For centuries, people from South Asia to Mesopotamia to Europe have traded lapis lazuli, a brilliant blue rock used to make ultramarine pigment, found in mines in present-day Afghanistan. Blue pigment rarely occurs in nature, making the rock exceptionally expensive; in medieval Europe, where the pigment was used to illustrate the most luxurious illuminated manuscripts, it was as valuable as gold. The pigment’s travels reflect the activity of merchants and artists around the world. Recently, researchers discovered the remains of lapis lazuli in the calcified dental plaque of a woman (identified as B78), buried in the cemetery of a small women’s monastery in Dalheim, in western Germany, between 997 and 1162. The findings, published this week in Science Advances by co-first authors Anita Radini of the University of York and Monica Tromp of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, senior author Christina Warinner, Ph.D. ’10, of the Max Planck Institute, and co-authors, suggest she was a skilled manuscript painter, providing the earliest direct evidence of the pigment’s use by a woman in Germany (Updated January 10, 2019, to reflect the names of the lead authors of this study).

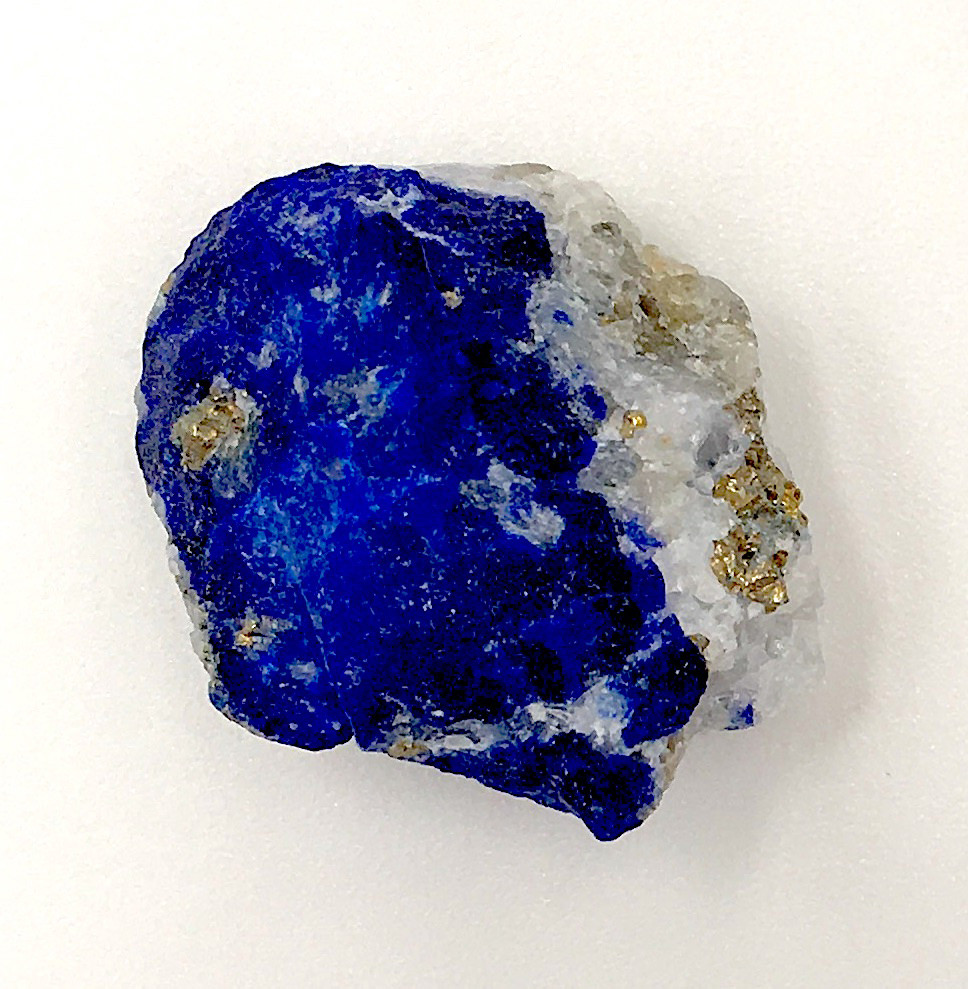

Lapis lazuli contains different minerals that contribute to its unique appearance, including lazurite (blue), phlogopite (white), and pyrite (gold).

Photograph by Christina Warinner

Historians have long assumed that monks rather than nuns were the main producers of books in medieval Europe. Few illuminated manuscripts were signed by their creators, but those that have a signature were usually signed by men. Recent evidence has challenged this assumption: twelfth-century correspondence between a monk and women’s monastery, for example, not far from the monastery at Dalheim, has shown that the production of deluxe manuscripts, using expensive materials, was outsourced to women scribes.

“A number of scholars have made considerable progress towards identifying female scribes and book painters from the Middle Ages and understanding their contributions to manuscript production in the past few decades,” co-author Alison Beach, a history professor at the Ohio State University, wrote in an email. “Still, the popular image of the monk as the scribe and artist is quite resilient, and changing a priori assumptions about male production, use, and ownership of books in the monasteries of medieval Europe—sometimes even within the field of Medieval Studies — is still sometimes a challenge.

“What makes B78’s teeth so special,” she added, “is that they provide material evidence of her activities (as we argue) as a user of ultramarine pigment over a consider period of time. This adds dramatically and vividly to the growing body of evidence for the role of women in producing books in the Middle Ages.”

The woman discovered at Dalheim “was plugged into a vast global commercial network stretching from the mines of Afghanistan to her community in medieval Germany through the trading metropolises of Islamic Egypt and Byzantine Constantinople,” Michael McCormick, Goelet professor of medieval history and a co-author of the paper, said in a news release. “The growing economy of eleventh-century Europe fired demand for the precious and exquisite pigment that traveled thousands of miles via merchant caravan and ships to serve this woman artist’s creative ambition.” McCormick chairs Harvard’s Initiative for the Science of the Human Past, an interdisciplinary research program that often collaborates with the Max Planck Institute, combining insights from the humanities and natural sciences to better understand human history.

The Dalheim monastery was destroyed in a fire during the fourteenth century, leaving scant evidence of work its residents might have done there. Recordkeeping at medieval women’s monasteries was limited, as are surviving manuscripts, but scholars have identified 4,000 books attributed to more than 400 women scribes working at German monasteries between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, the study reports.

Foundations of the church associated with a medieval women’s religious community at Dalheim, Germany.

Photograph by Christina Warinner

The bright blue particle’s discovery was an accident: in 2014, the team had been searching for plant remains in dental plaque to study their medieval subjects’ diets. They estimated that the woman was between 45 and 60 years old when she died, and, with help from physicists at the University of York, identified the blue particles as lapis lazuli. The pigment was dispersed in the woman’s dental plaque like a powder, in many small fragments, suggesting that it accumulated over time rather than all at once.

But how did the pigment end up in her mouth? The team proposed four possible explanations: the most likely, they believe, is that she was directly involved in making books, licking the ends of her brushes to make a fine point, which would explain the distribution of the fragments in her mouth. Later artist manuals, the study notes, refer directly to this technique. Another possibility is that the woman prepared pigment from lapis lazuli, either for herself or another scribe, and inhaled it, though this is less likely because it’s not clear that European artisans had mastered the technique necessary to create bright blue pigment from the rock; they may instead have imported the powder as a finished product.

Two curious, but improbable, scenarios are also mentioned: lapis was believed to have healing properties and so was sometimes used in medicines, but there is little evidence that ingesting it directly was widespread in Germany during this period. A final explanation—kissing painted images in books as a devotional practice—is not attested in European texts until three centuries later.

“The case of Dalheim raises questions as to how many other early women’s communities in Germany, including communities engaged in book production, have been similarly erased from history,” the researchers write. New methods in archaeology, such as those that allow scholars to identify tiny fragments in dental remains, can supplement the written record, and promise to better illuminate the surprising, hidden dimensions of history.