In the United States and throughout the world, migration is a newly urgent issue—more people are displaced today than has ever been recorded. Yet migration has also shaped and reshaped the world for as long as humans have lived. A new Harvard Art Museums exhibition, spanning media, places, and times, explores these two dimensions of human movement, and the space in between. Its images and objects—of people, but also of landscapes, things left behind, ghostly traces—present a vision of migration that, however contested today, is central to world history. Walking through the gallery, one is confronted with the sense that migration is not a special or marginal part of the human experience. It is a constant, pervasive consequence of human conflict and disaster—a reflection of the will to survive, and humans’ capacity to make their world anew.

“Crossing Lines, Constructing Home: Displacement and Belonging in Contemporary Art,” which runs through January 5, begins with a passport. Walk up closer to it, and it becomes clear the passport is a fabrication, a Spanglish document created by Puerto Rican artist Adál Maldonado for his imaginary country, El Spirit Republic of Puerto Rico. “The longer you look at it, the more it breaks up your sense of what is real,” says Mary Schneider Enriquez, a curator of modern and contemporary art. Puzzling over the document, the components of a passport appear surreal, silly. In place of the national seal usually found on passports is a domino: a trick, a roll of the dice that determines who leaves and stays, and, often, who lives and dies.

Richard Misrach’s “Border Patrol Target Range, Near Gulf of Mexico, Texas,” 2013.

Gift of the artist, 2018.112. © Richard Misrach; image courtesy of the artist and Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

Bill McDowell’s “Untitled (approaching the border, Roxham Road),” 2018, from the series Almost Canada

Fund for the Acquisition of Photographs, 2019.82. © Bill McDowell; courtesy of the artist. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

The symbolism of passports echoes the exhibition’s larger interest in borders—such a focal, contested part of today’s discourse on migration. What are borders, and what do they mean? They don’t merely come into existence: they are constructed, and reflect choices about how to carve up places and landscapes. A large back wall of the exhibit displays images of the southern and northern U.S. borders. An oversized photograph of a Border Patrol target practice range in Texas, by Richard Misrach, is unforgettable, with nine human-shaped decoys shot through with bullets, and the foreground littered with gun casings. In a photo of the U.S.-Canadian boundary by Bill McDowell, taken from the dashboard of a car, the border barely exists. “You can just roll up in your car,” says co-curator Makeda Best, who leads the museums’ photography curation. “There’s no line; it’s not militarized.” The photo looks like it could have been taken on anyone’s smartphone. The southern and northern border photos, Best explains, each enact a kind of looking: the “militarized gaze” of the Border Patrol, and the perspective of someone driving up to Canada, from the safety of their car.

“Crossing Lines” is only the most recent contribution to Harvard’s campus-wide conversation on migration and displacement. This summer, the Harvard Global Health Institute hosted a panel on the emergency at the U.S.-Mexico border, where lawyers and public-health professionals reported that children and families were being abused and irrevocably harmed by the current administration’s policies toward immigrants. In April, Masha Gessen’s distinguished Tanner Lectures on Human Values invited listeners to question what it even means to restrict human movement—a question that resounds alongside an exhibition photo that shows the southern border as a vast, empty desert landscape, cut in half by a rusty barrier.

These contemporary pieces reflect how photographers today think of their work: not merely documenting some fixed version of reality, but also as participants who shape the way their subjects are looked at.

Most of the works in the “Crossing Lines” are new acquisitions commissioned by Enriquez and Best. These contemporary pieces, Best says, reflect how photographers today think about their work: not merely documenting some fixed version of reality, but also as participants who shape the way their subjects are looked at. Another piece by Bill McDowell, a photo of the fragments of an asylum seeker’s testimony found at the U.S.-Canadian border, reveals incomplete glimpses of who this person was: a refugee forced to leave Nigeria because of sexual orientation. Says Best, “These slower methods of working speak to how contemporary photographers are interested in a slower process and layered process that recognizes their own position as producers—and not just the idea that photography can offer some sort of evidence.”

Photography may have moved beyond a “view from nowhere” idea of objectivity, but the images chosen for the exhibit still serve a documentary role, with the ability to reveal and surprise. Beside well-known symbols of migration—passports, the southern border—are others that visitors may never have heard of, or may not have registered as a type of migration. A 2008 photograph by Jim Goldberg shows a family living at a waste-management facility on the outskirts of Hyderabad; rising temperatures have forced families like these to abandon their farms, a reminder that the climate crisis is now reality. Another photo from Bill McDowell’s “Almost Canada” series shows the open entrance to a narrow Underground Railroad tunnel, inviting viewers to imagine climbing inside—another kind of migration.

Jim Goldberg, “Home, Hyderabad, India,” 2008, printed 2019.

Francis H. Burr Memorial Fund, 2019.104. © Jim Goldberg; courtesy Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

The flip side of boundaries and borders—the coercion and control exercised over movement—is the idea that migration gives rise to new cultures that are always remaking the world. “Crossing Lines” considers these “hybrid spaces, identities, languages, and beliefs,” from the perspective of an individual’s psychology as well as from that of the greater culture. A woodcut print by Indian artist Zarina shows 36 abstract, geometric representations that bring to mind parts of homes she has lived in—a door, the night sky—with Urdu and English inscriptions under each. After the partition of India, Zarina’s family and millions of others were displaced and became refugees in their own countries. Her work, titled Home Is a Foreign Place, reflects the idea that returning home means going to a place that is not hers.

Zarina’s work is an evocative mediation on how immigrants see themselves—but what about when they are looked at, seen from the outside by their host culture? A large slide show displays a set of 80 photos by Candida Höfer of Turkish families in Germany in the 1970s. The immigrants are captured in intimate portraits in their homes, and in candid shots on streets and in shops and public parks. “Turks in Germany” was taken while the country was ending its postwar foreign-labor program, but, as an exhibit label explains, this series “contradicted the then-widespread notion that ‘guest workers’ were temporary. By the mid-1970s, Turks were the largest immigrant population in the country and, as Muslims, the least accepted.” Höfer’s series represented the immigrants in a German visual discourse “from which they remained otherwise conspicuously absent,” a label explains. These new Germans, the photos seem to announce, were here to stay.

Dylan Vitone, “friday night,” 2001, printed 2019. From the series South Boston

Fund for the Acquisition of Photographs, 2019.115. © Dylan Vitone. Image courtesy of Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum

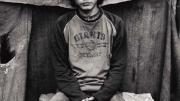

The final works that visitors see in “Crossing Lines” are a set of six photos taken by Dylan Vitone in 2001, representing working-class residents of historically Irish South Boston; and REMAINS, a film by Irish artist Willie Doherty describing his and his son’s kneecapping during the Troubles in Northern Ireland. Playing on a loop in a black box offset from the gallery space, REMAINS is an immersive, eerie experience. Enriquez felt it was essential for the museums to represent the importance of Irish immigration for Boston, and the enduring consequences of conflict about identity and sovereignty in Ireland. The subjects of Vitone’s black-and-white portraits, like those of “Turks in Germany,” stare straight into the camera, announcing their place in their homes and communities: a reminder that migration, past and present, is all around us.